Devin Thorne, China’s T-AGOS: The Dongjian Class Ocean Surveillance Ship, China Maritime Report 36 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, March 2024).

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD A FULL-TEXT PDF.

About the Author

Mr. Devin Thorne is a Principal Threat Intelligence Analyst with Recorded Future. He specializes in the use of publicly available Chinese-language sources to explain China’s security strategies and their implementation, with a focus on maritime security, national defense mobilization, military-civil fusion, and propaganda. He was previously a Senior Analyst with the Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS) and has also conducted research on behalf of the Korea Institute for Maritime Strategy, Hudson Institute, and U.S. Department of State. Devin holds a B.A. from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and an M.A. from the Johns Hopkins University–Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies. He lived, studied, and worked in China for multiple years. He speaks Mandarin.

Summary

Since 2017, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has commissioned a new class of ocean surveillance vessel into its order of battle: the Type 927. Similar in design and function to the U.S. Navy’s Victorious and Impeccable class T-AGOS ships, the Type 927 was introduced to help remedy the PLAN’s longstanding weakness in anti-submarine warfare. The PLAN has likely built six Type 927 ships to date, most based for easy access to the South China Sea. In peacetime, these ships use their towed array sonar to collect acoustic data on foreign submarines and track their movements within and beyond the first island chain. In wartime, Type 927 vessels could contribute to PLAN anti-submarine warfare operations in support of a range of different maritime campaigns. However, their lack of self-defense capabilities would make them extremely vulnerable to attack.

Introduction

Since 2017, Chinese shipyards have launched, and the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has likely commissioned, six new ocean surveillance ships. These ships—designated the Type 927 or Type 8161 by the PLAN and the Dongjian class by the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI)2—provide the PLAN an improved capability for acoustic detection of undersea threats. In peacetime, they will collect acoustic signatures and monitor the activities of foreign submarines operating in China’s claimed maritime spaces, strengthening the PLAN’s ability to seize the initiative if war erupts.3 In wartime scenarios, Type 927 ships will very likely support a range of offensive and defensive campaigns with an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) component, in coordination with other surface, air, undersea, and shore-based systems, sensors, and platforms. The Type 927’s helipad likely enables it to work directly with an ASW helicopter to precisely detect, localize, identify, and attack enemy submarines.4

Like the ocean surveillance ships of other modern navies, Type 927 ships almost certainly have both a passive and low-frequency active (LFA) sonar capability. The PLAN’s new ocean surveillance fleet will likely create challenges for the undersea operations of the United States (U.S.), Japan, and others in the Asia-Pacific region, imposing new obstacles to their stealthy navigation and security. The challenges will likely be greatest within, and along the periphery of, the first island chain, where the activities of Type 927 ships will likely concentrate.5

This report is divided into three sections. Section one discusses the strategic and operational environment informing China’s investment in ocean surveillance ships and how they will likely be used. Section two examines what is known (and unknown) about the Type 927 class, including vessel identifiers, basing, layout, and sonar capabilities, as well as the PLAN’s previous generation of ocean surveillance ships. Section three analyzes the likely peacetime and wartime roles of Type 927 ships as well as the likely geographic focus of their operations. … … …

Conclusion

China’s new-generation of ocean surveillance ships is almost certainly designed to help (in coordination with other sensors and platforms) alleviate longstanding weaknesses in the PLAN’s ASW capability and in China’s undersea security more broadly. That so many Type 927 ships have been built so fast—six were likely delivered between 2017 and 2022—underscores the importance that Chinese military leaders place on the undersea domain and on addressing shortcomings in long-range undersea detection and target identification. The pace of construction also suggests China has successfully developed adequate long-range passive and (almost certainly) LFA sonar technologies, as well as acoustic data processing techniques. However, the PLAN’s sonar systems likely remain behind those of the U.S. and others in performance and reliability.

While strengthening China’s national defense posture is the primary motivation for building the Type 927 fleet, these ships further the PLAN’s offensive ambitions as well. SMS 2020, for example, calls for developing the ability to establish “comprehensive sea area control” on the basis of “all-weather, omni-directional, multi-dimensional, multi-band battlefield perception, target recognition, tracking, and positioning capabilities.” 115 Type 927 ships will very likely, in certain scenarios, contribute to this and related goals, such as exercising command of the sea during a conflict.

Thus, in peacetime and wartime, the operations of Type 927 ships will likely create new challenges for American, Japanese, and other submarines operating regionally. Some Chinese sources express that American ocean surveillance ships have an “interfering” effect on China’s submarine operations and other undersea military activities.116 Along similar lines, other Chinese sources suggest that Type 927 ships can help China interfere in, and thwart, the “harassing” activities of U.S. submarines operating in the South China Sea.117 Should China deploy these ships to surveil waters near foreign naval bases, for instance, they will likely become obstacles to free, stealthy movement into and out of those ports. The Type 927 may also make stealthy navigation of China’s maritime periphery more difficult in general as part of the PLAN’s likely desire to impose a buffer zone between foreign submarines and China’s strategic naval ports. As China’s undersea detection capabilities continue to improve and these ships are further integrated into maturing PLA C4ISR networks, Type 927 ships will likely increase the threats to foreign submarines.

PREVIOUS STUDIES IN THIS CMSI SERIES:

China Maritime Reports are short papers exploring topics of current interest related to China’s rise as a maritime power. Written by members of the China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI) and other experts at the direction of the CMSI Director, they cover topics as diverse as China’s maritime militia, overseas port development, and amphibious warfare.

J. Michael Dahm, Beyond Chinese Ferry Tales: The Rise of Deck Cargo Ships in China’s Military Activities, 2023, China Maritime Report 35 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, February 2024).

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD A FULL-TEXT PDF.

From CMSI Director Christopher Sharman:

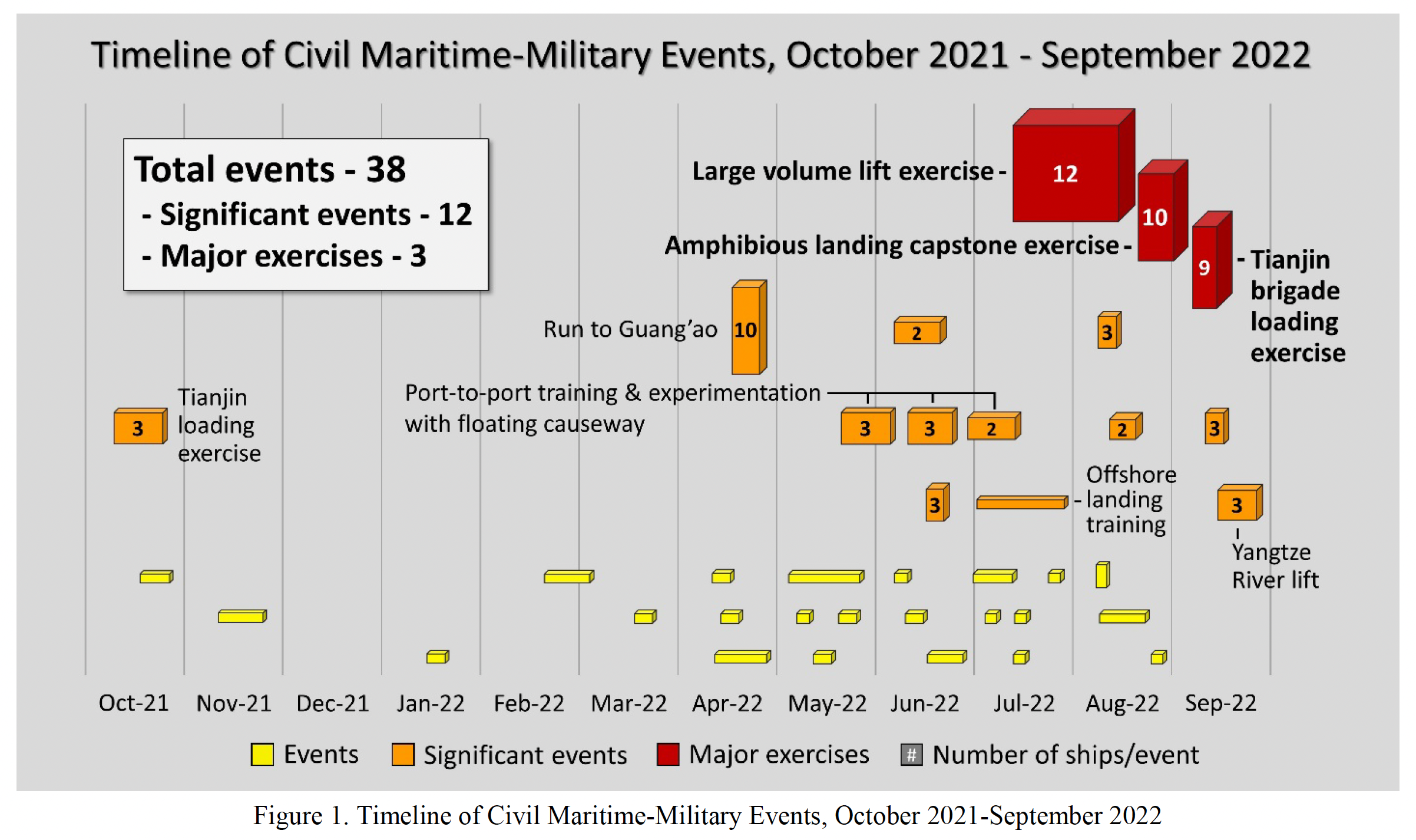

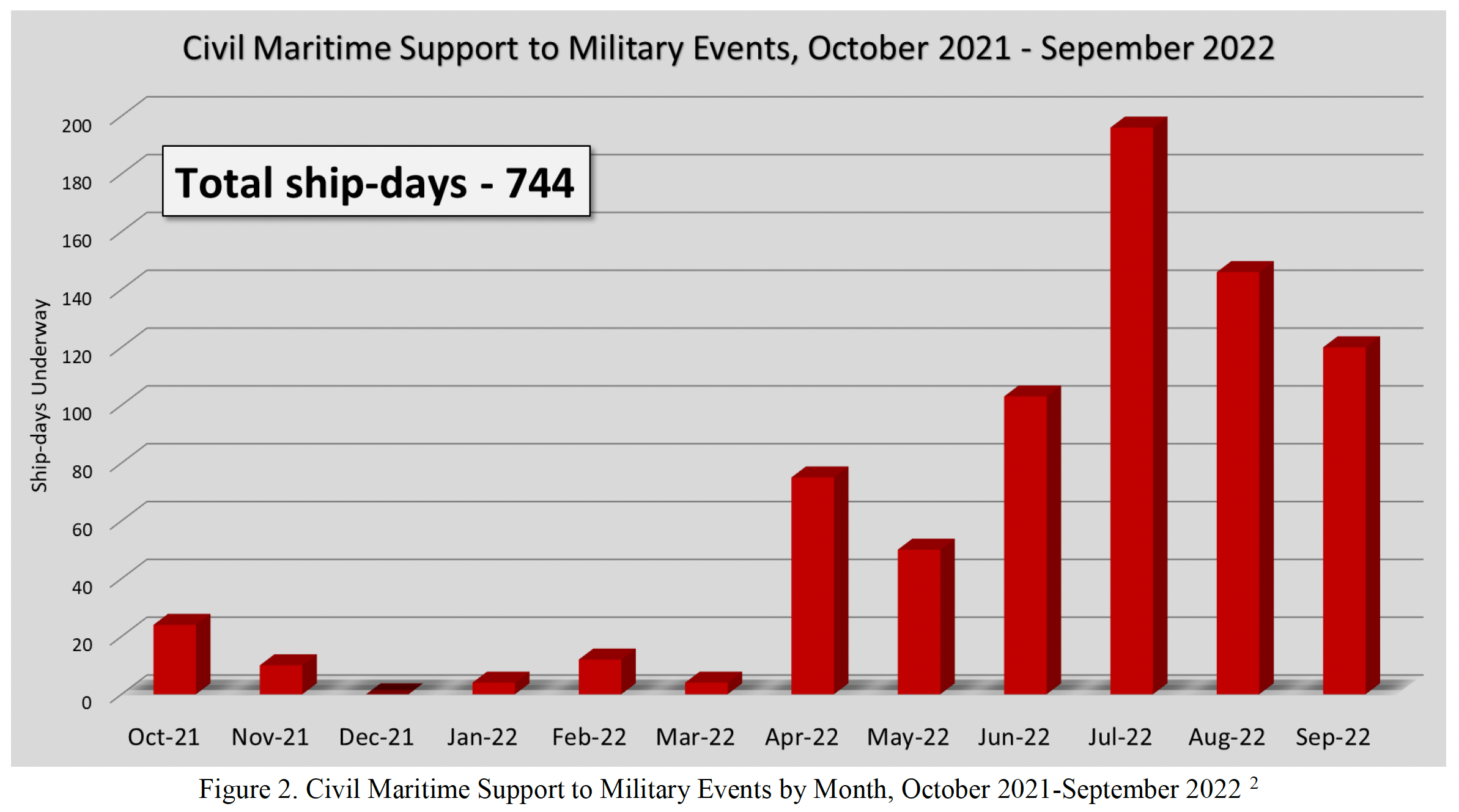

The China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI) is pleased to provide you with China Maritime Report (CMR) #35, “Beyond Chinese Ferry Tales.”

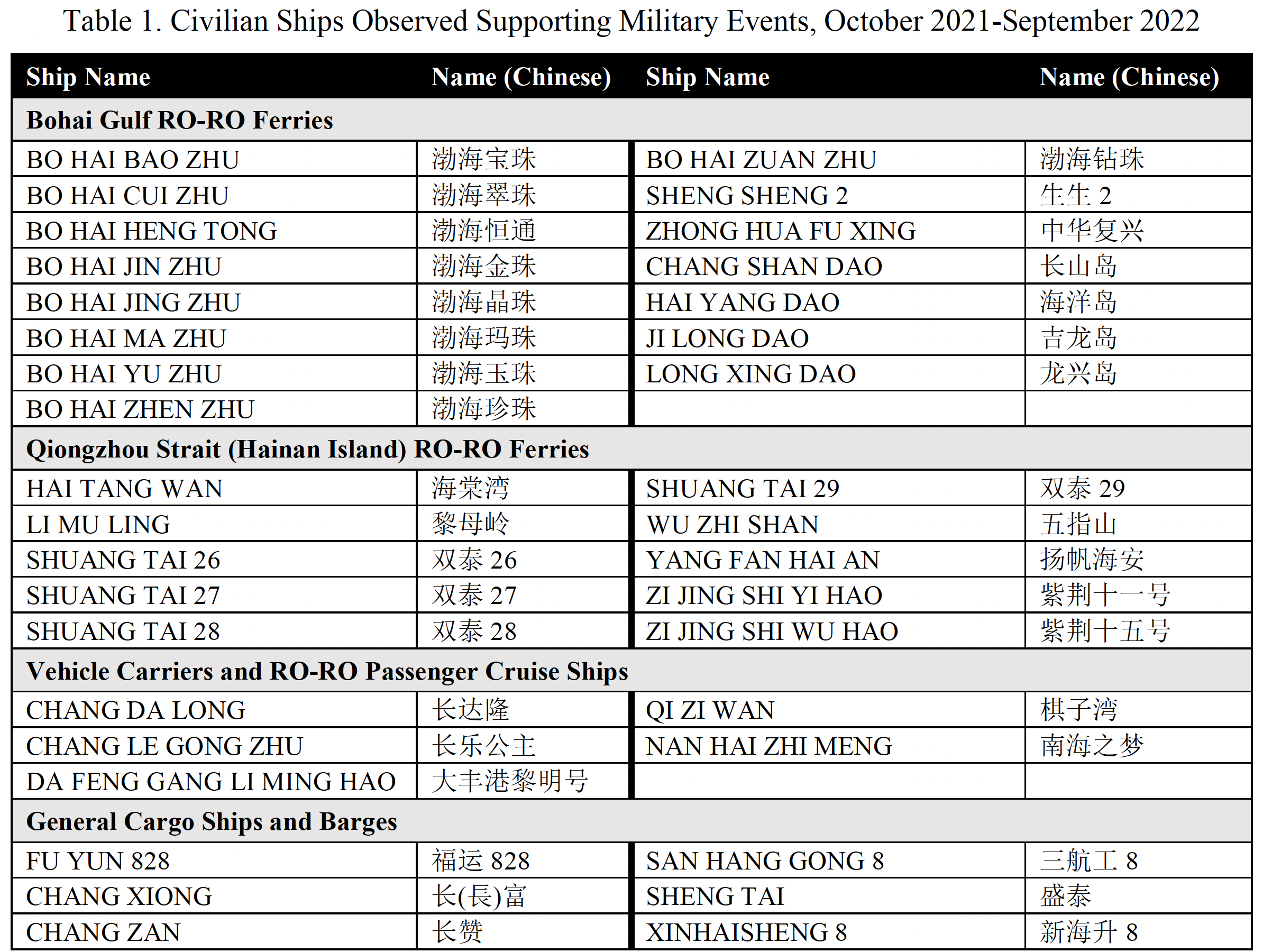

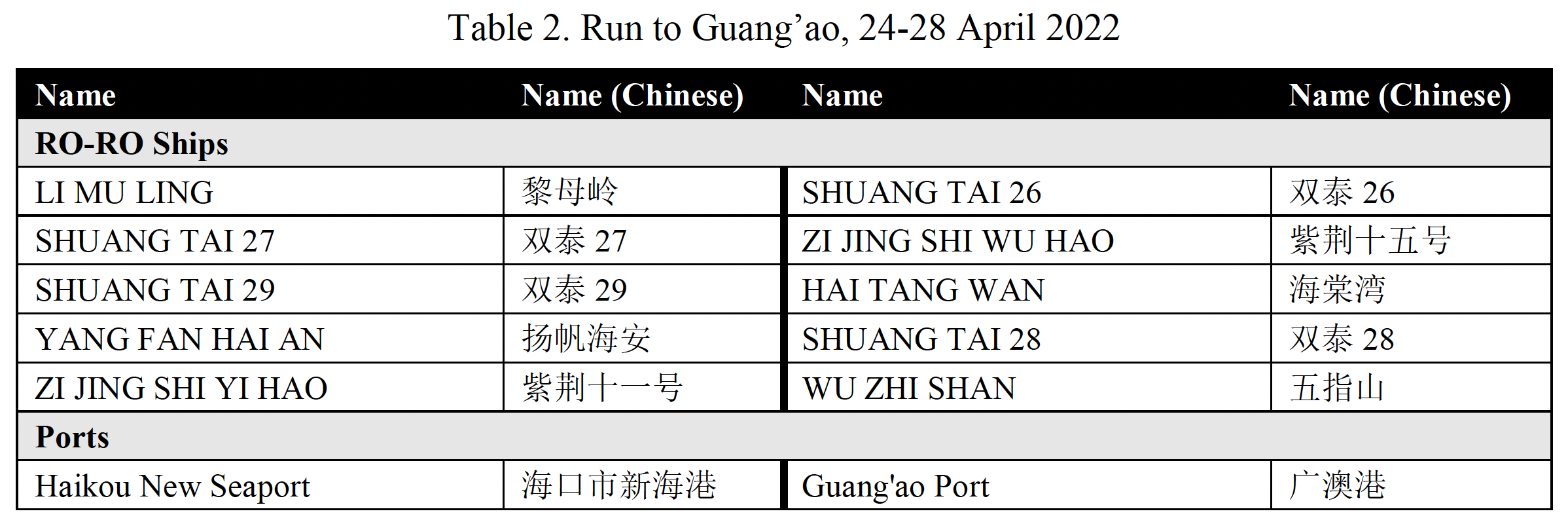

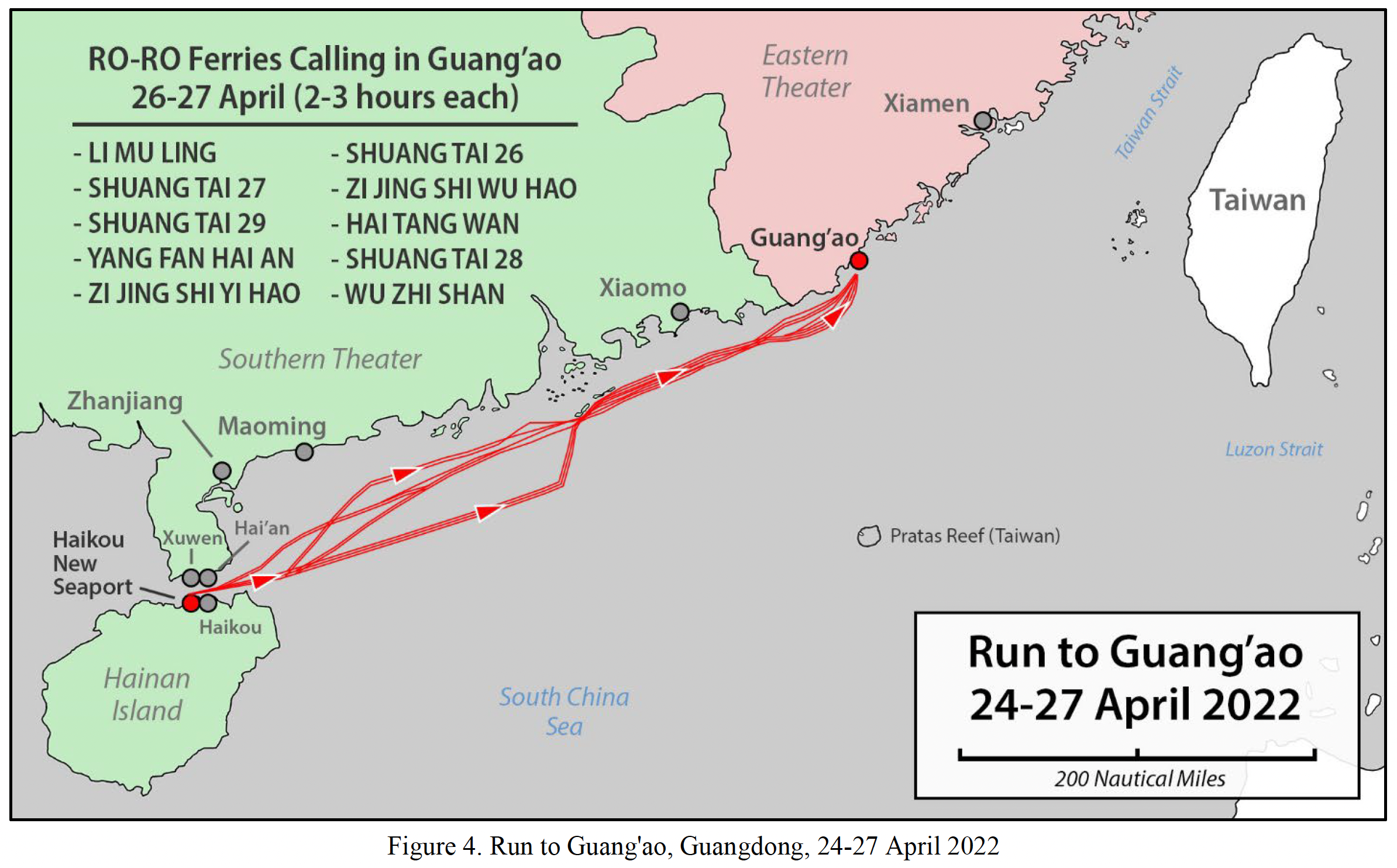

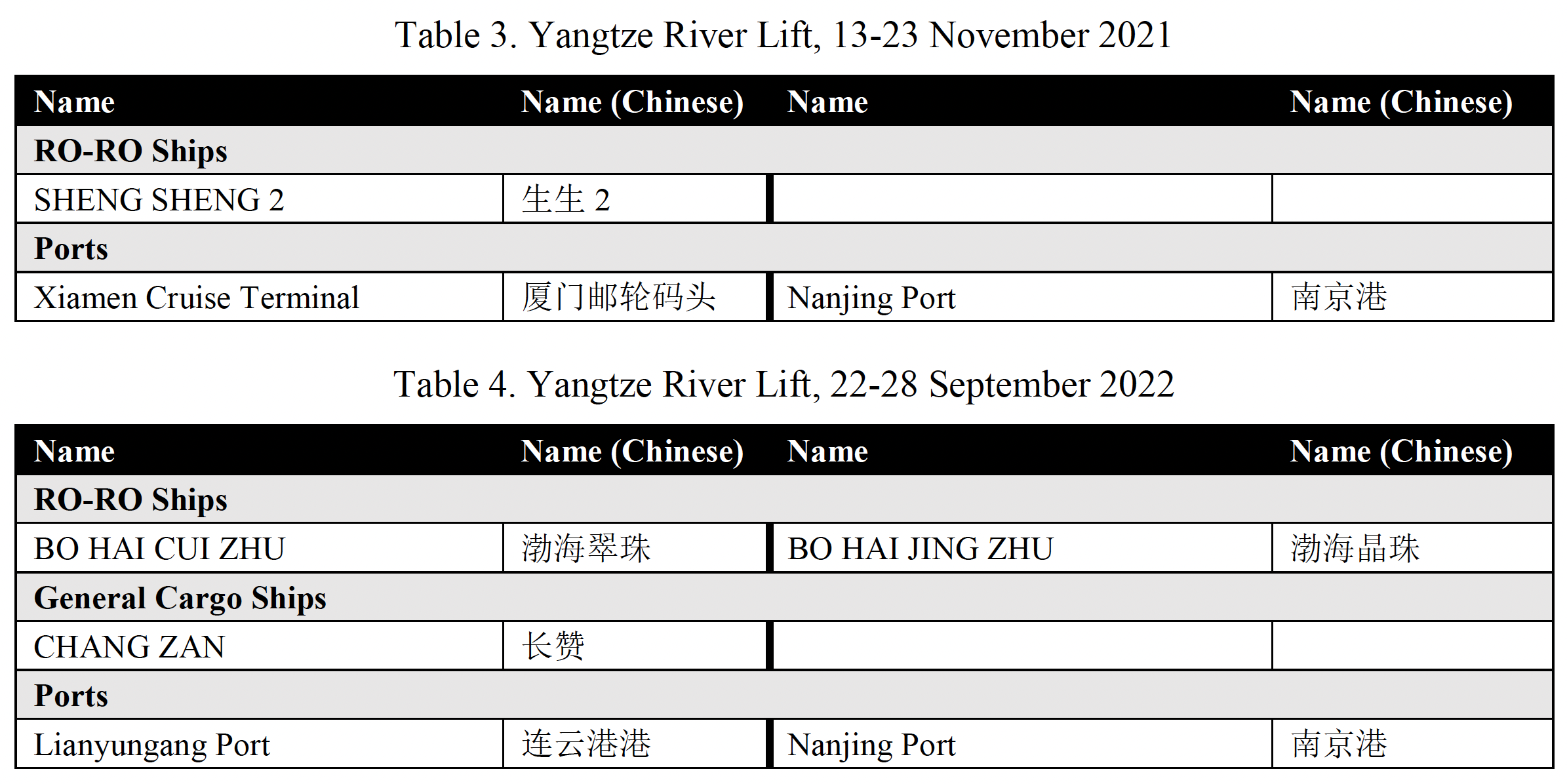

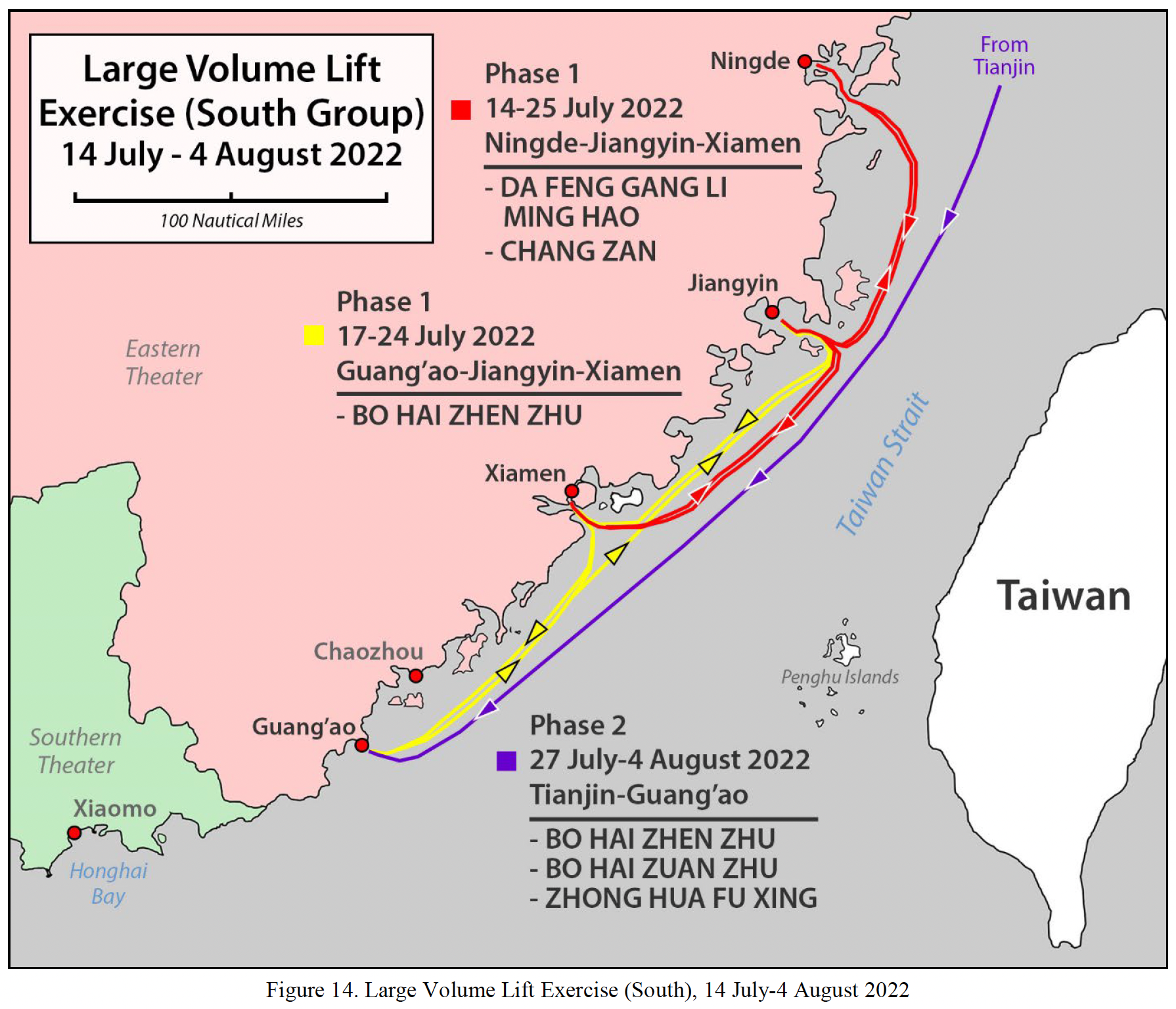

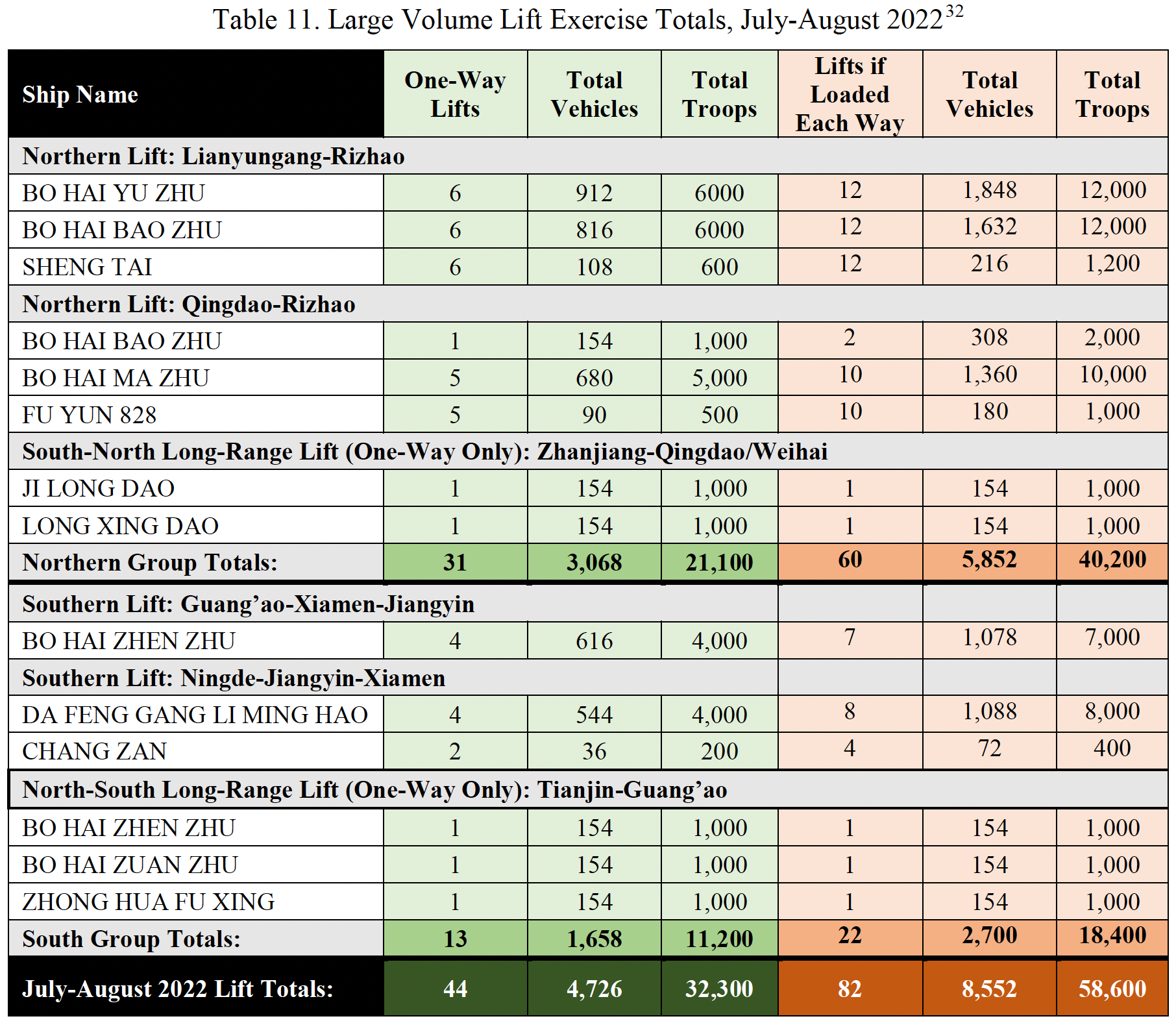

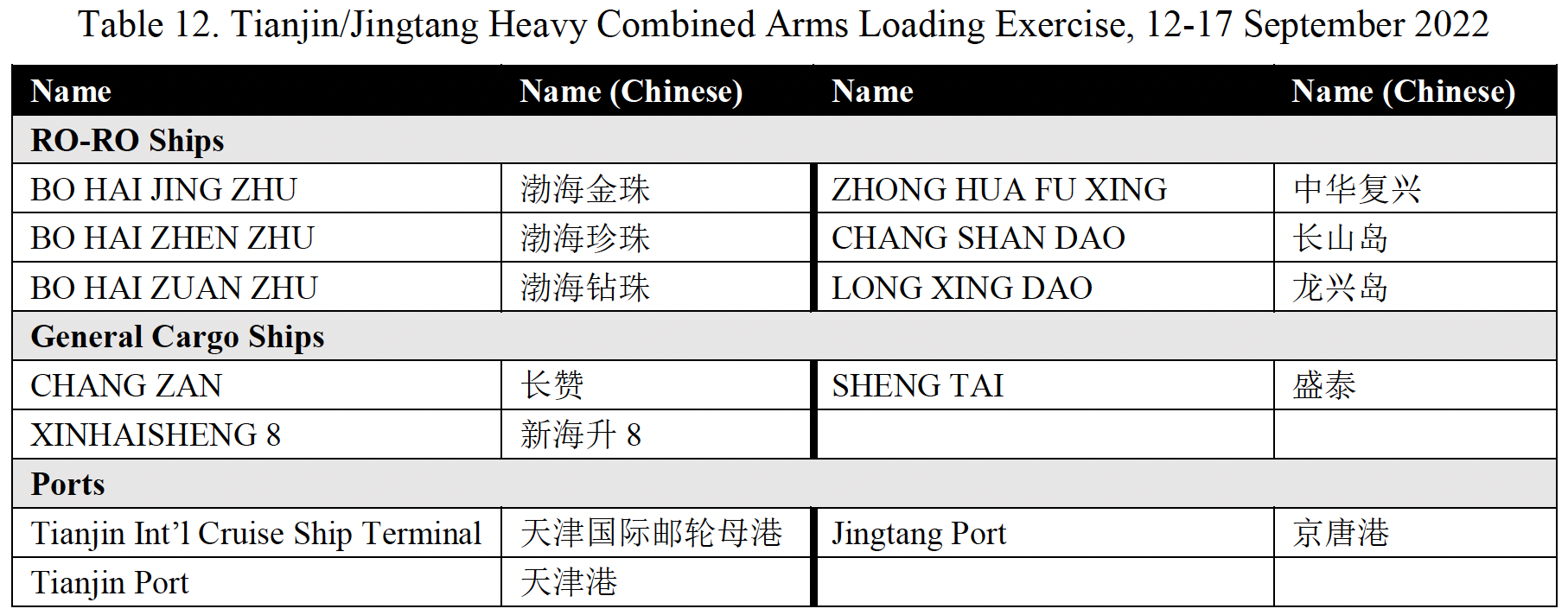

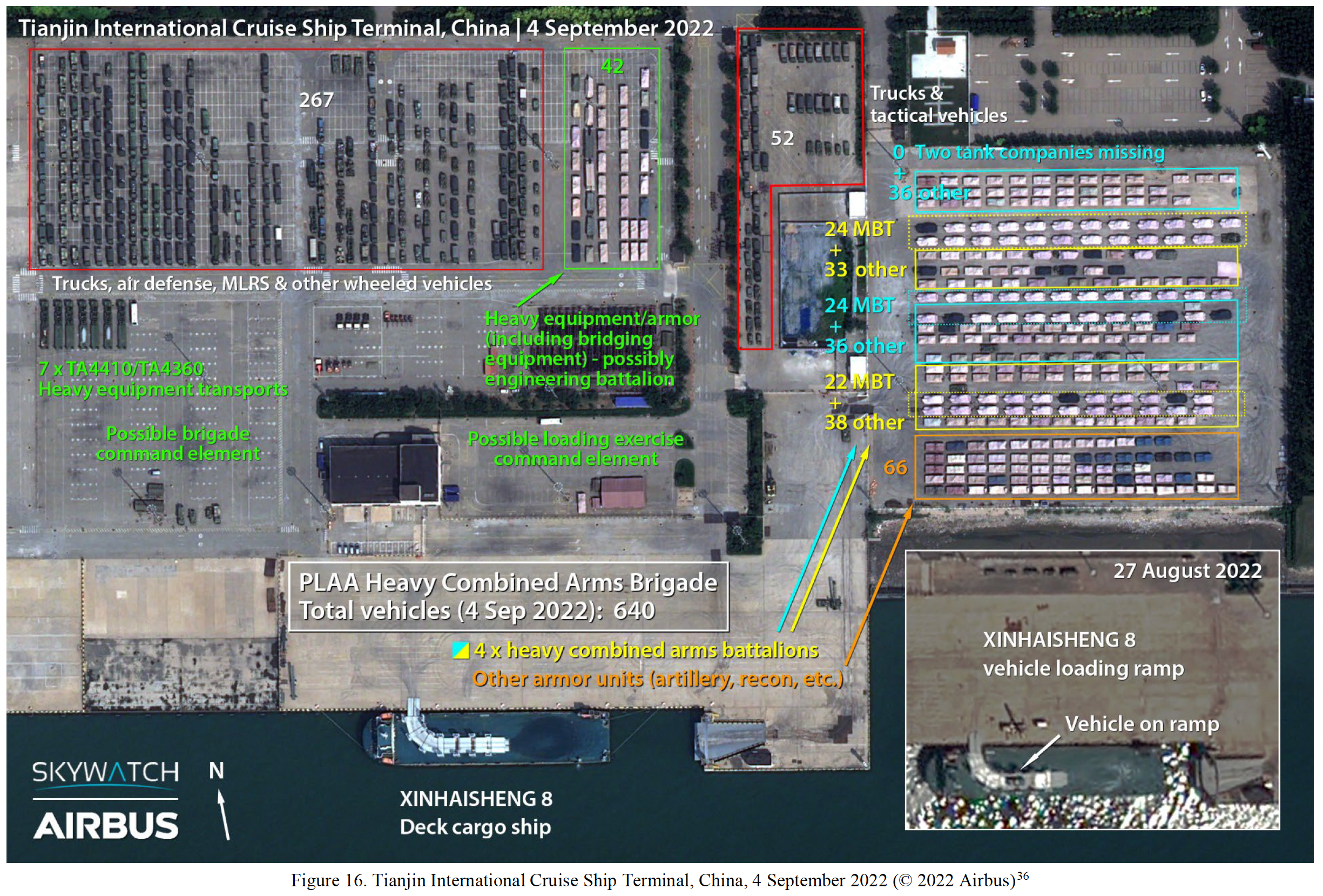

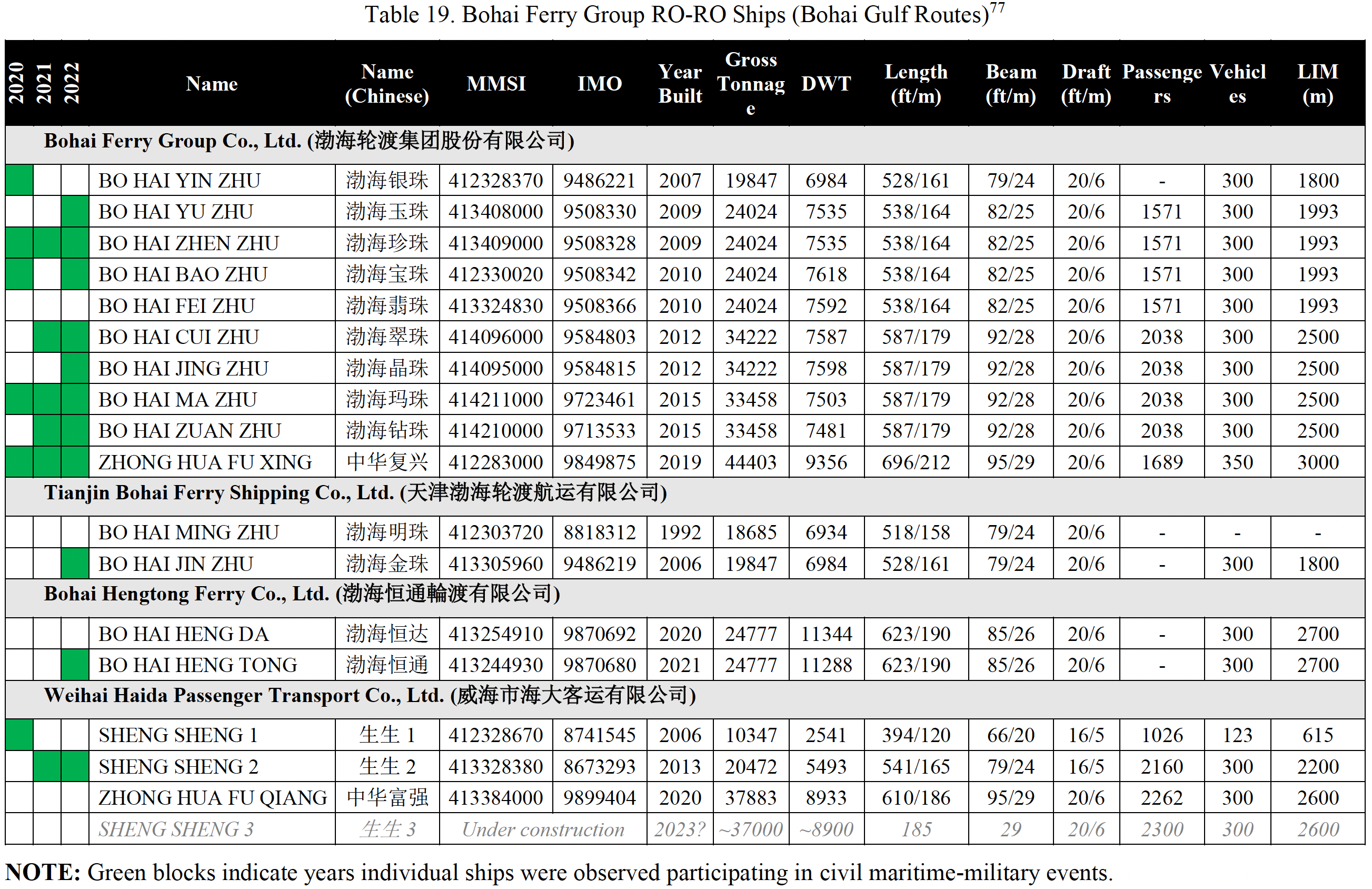

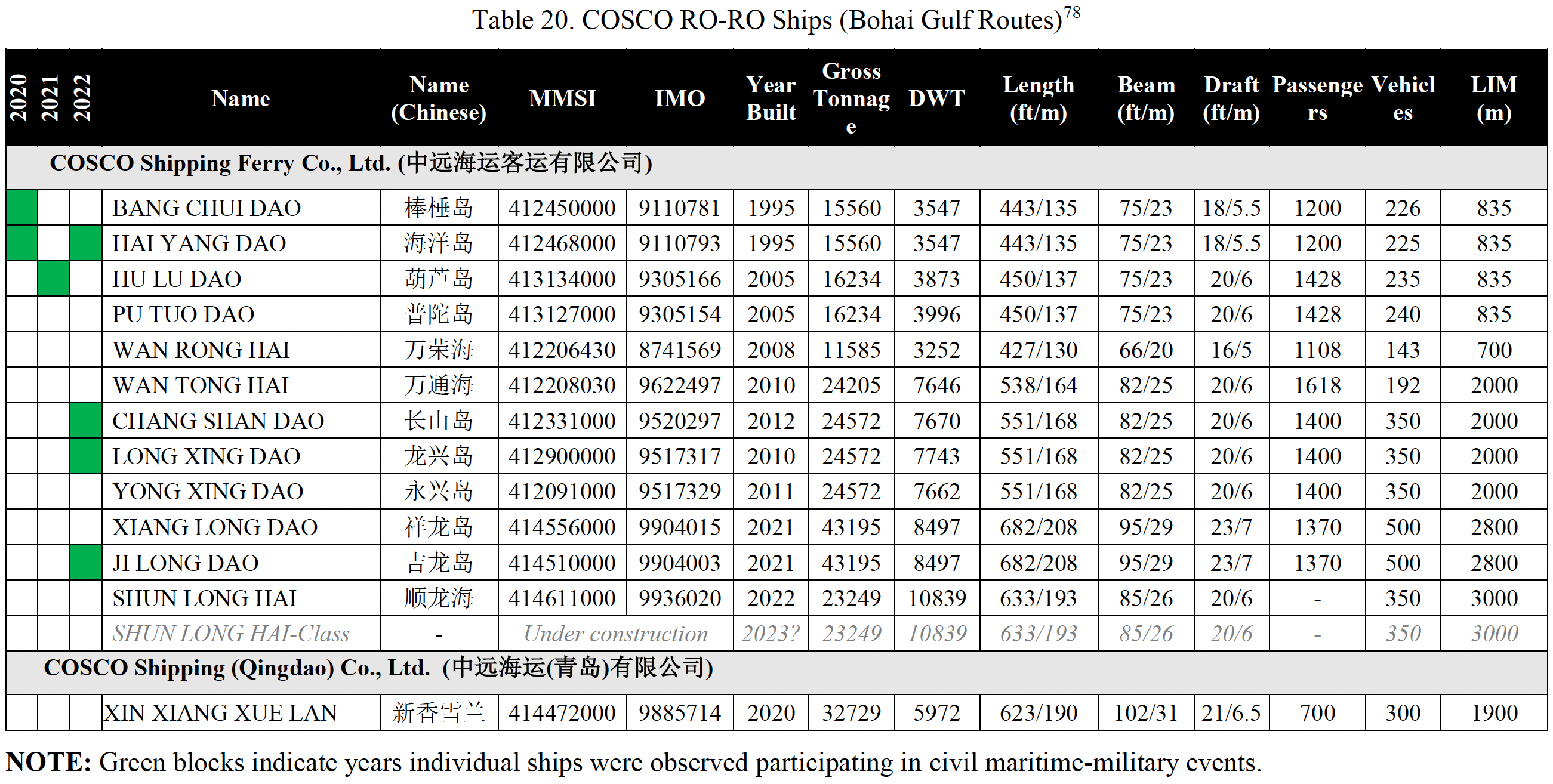

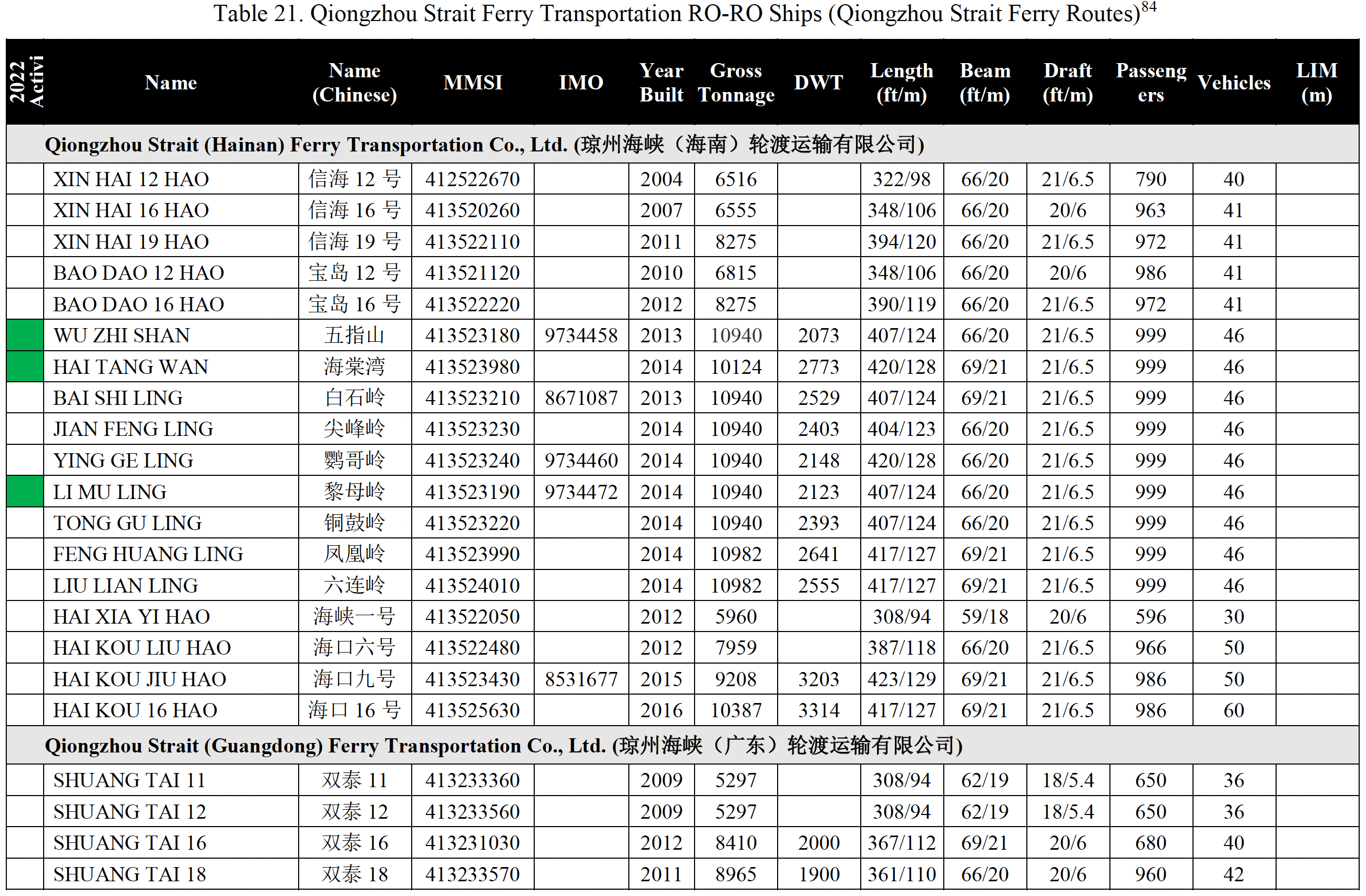

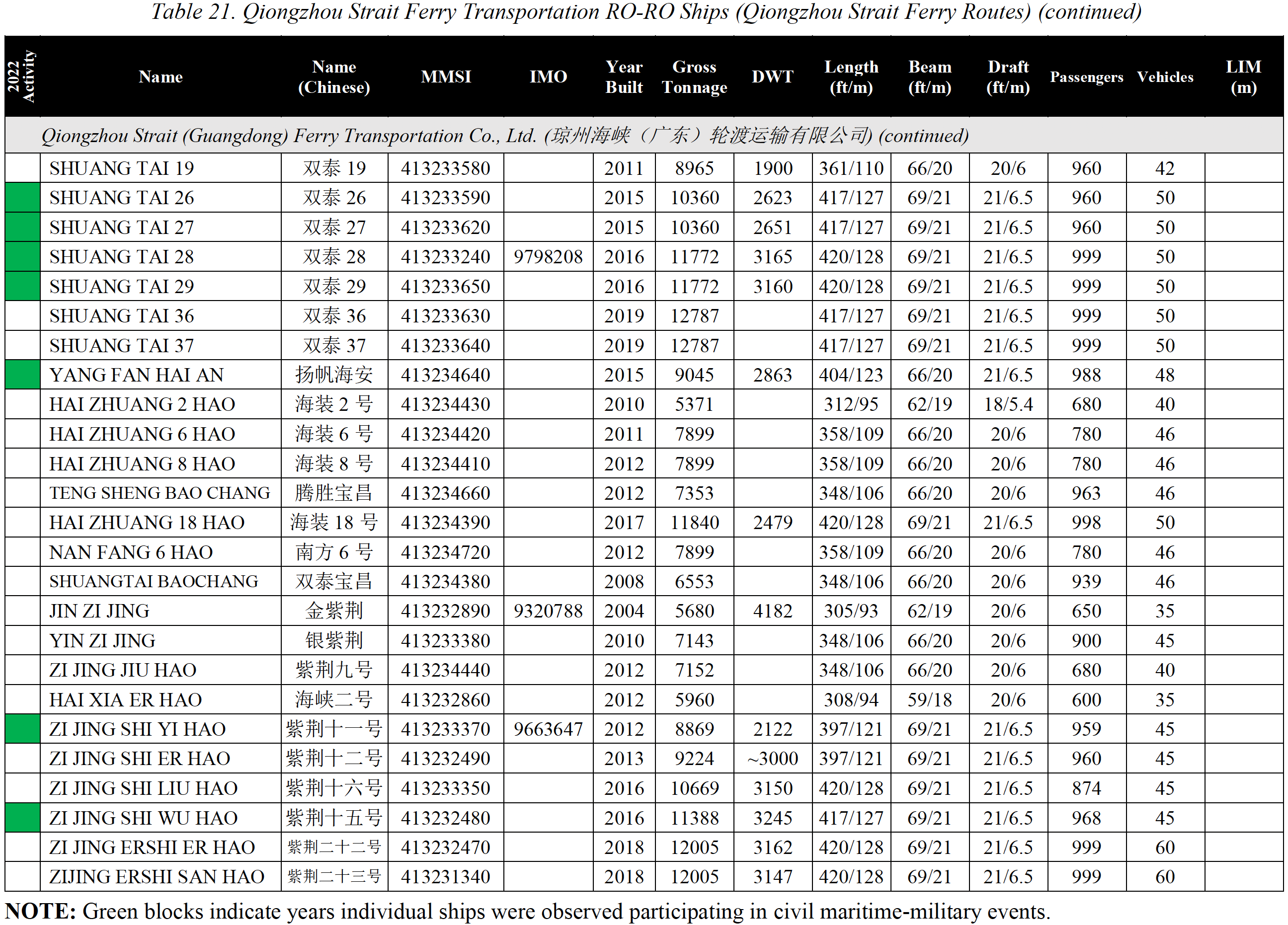

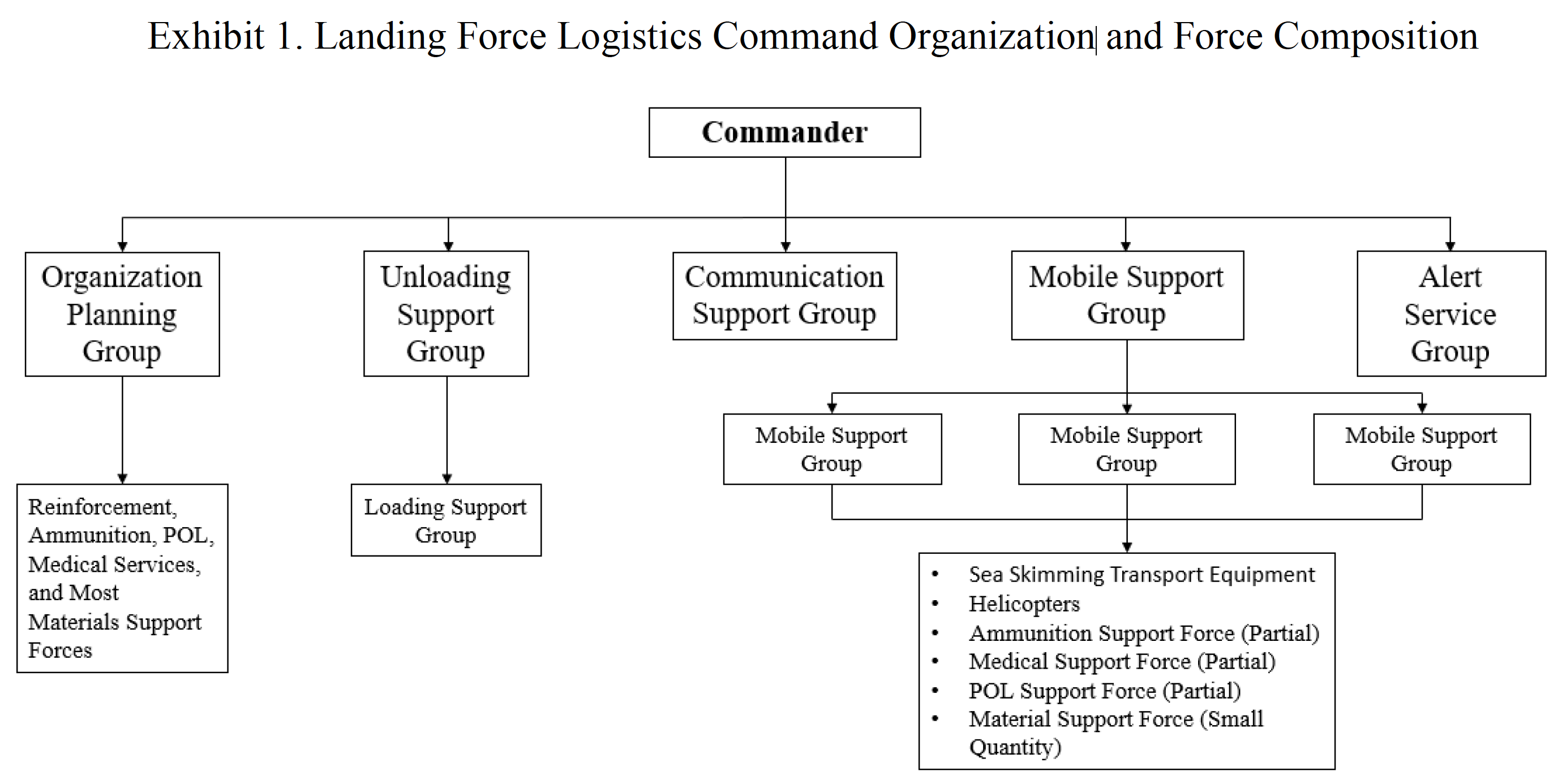

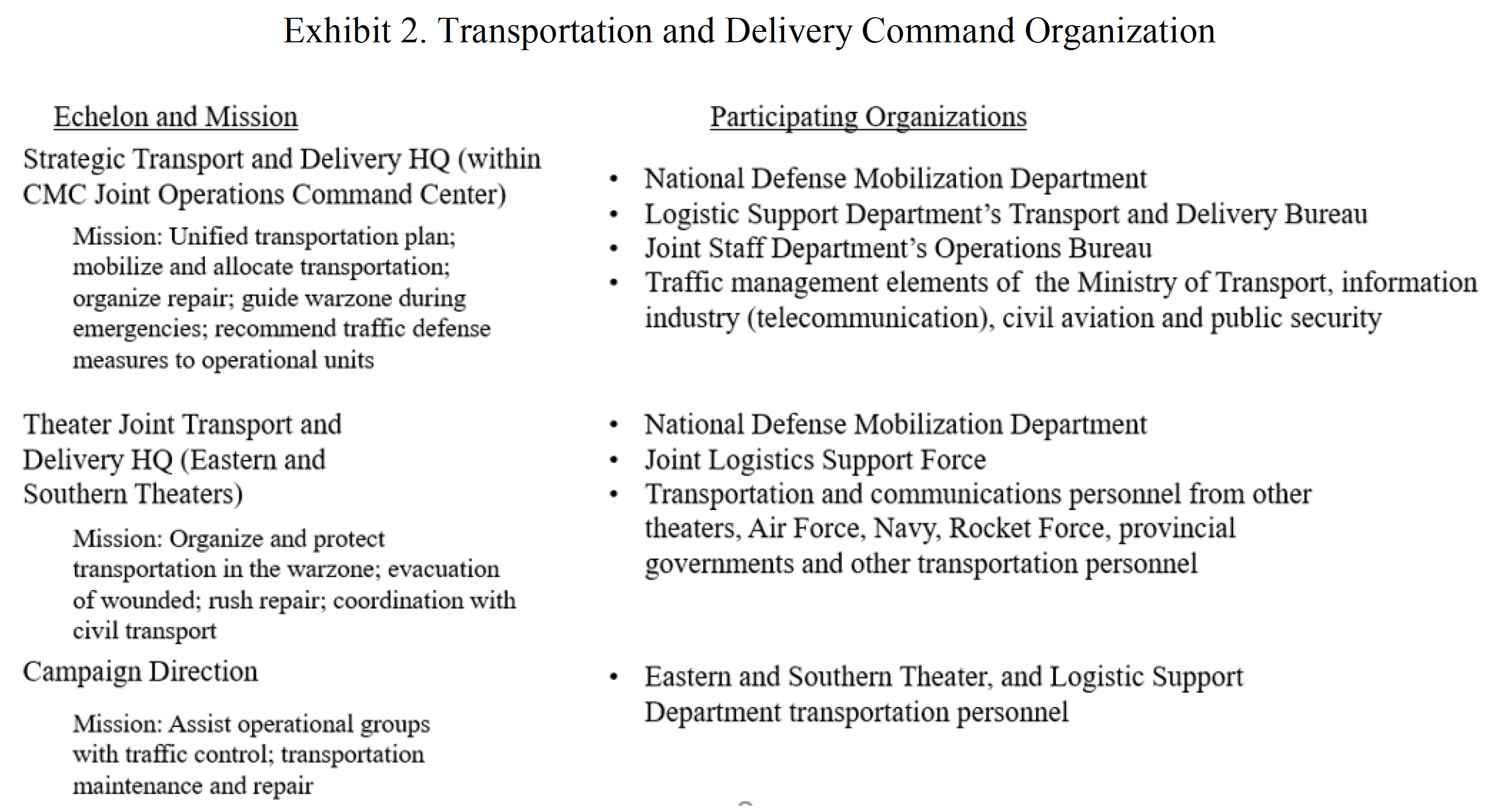

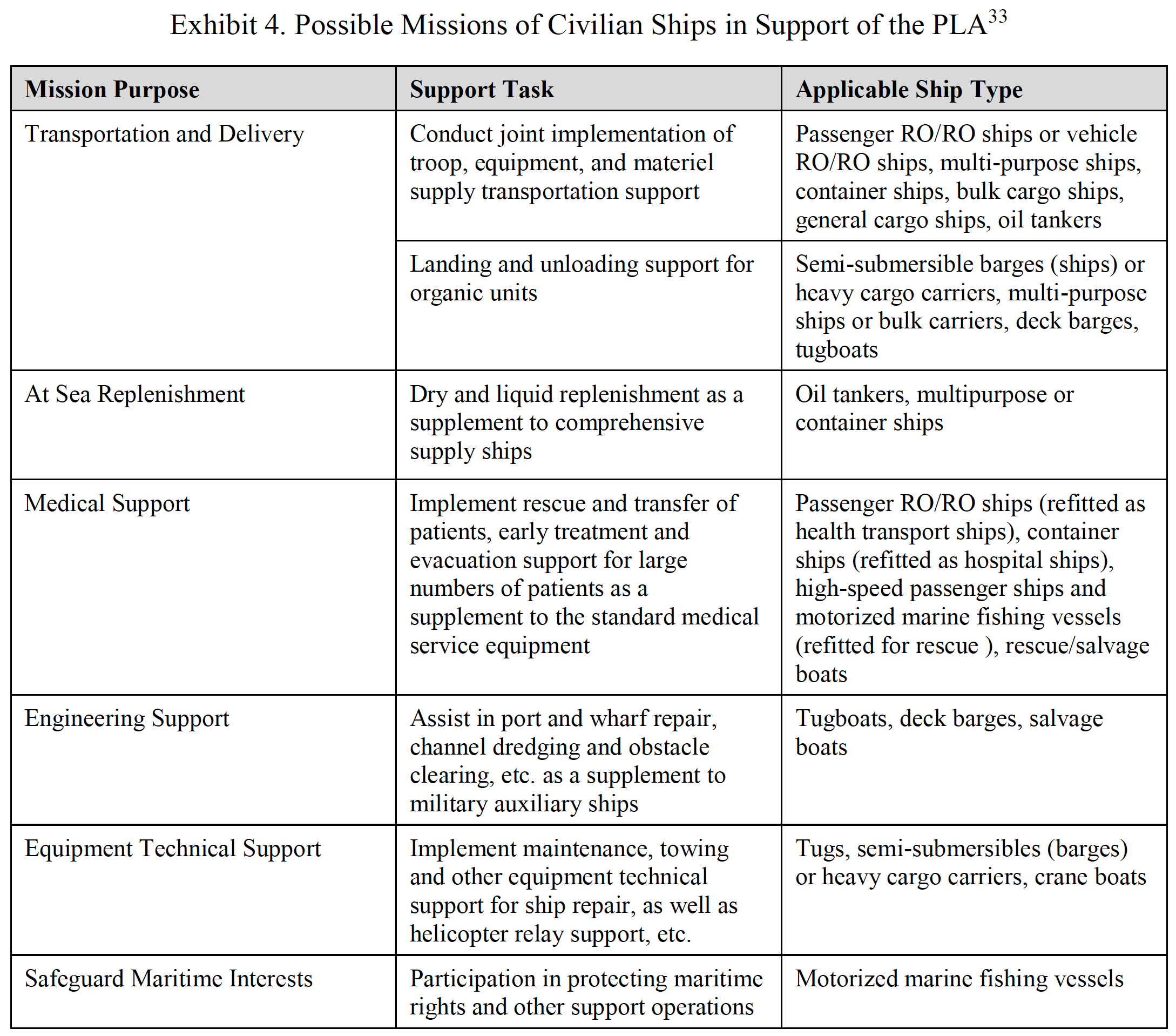

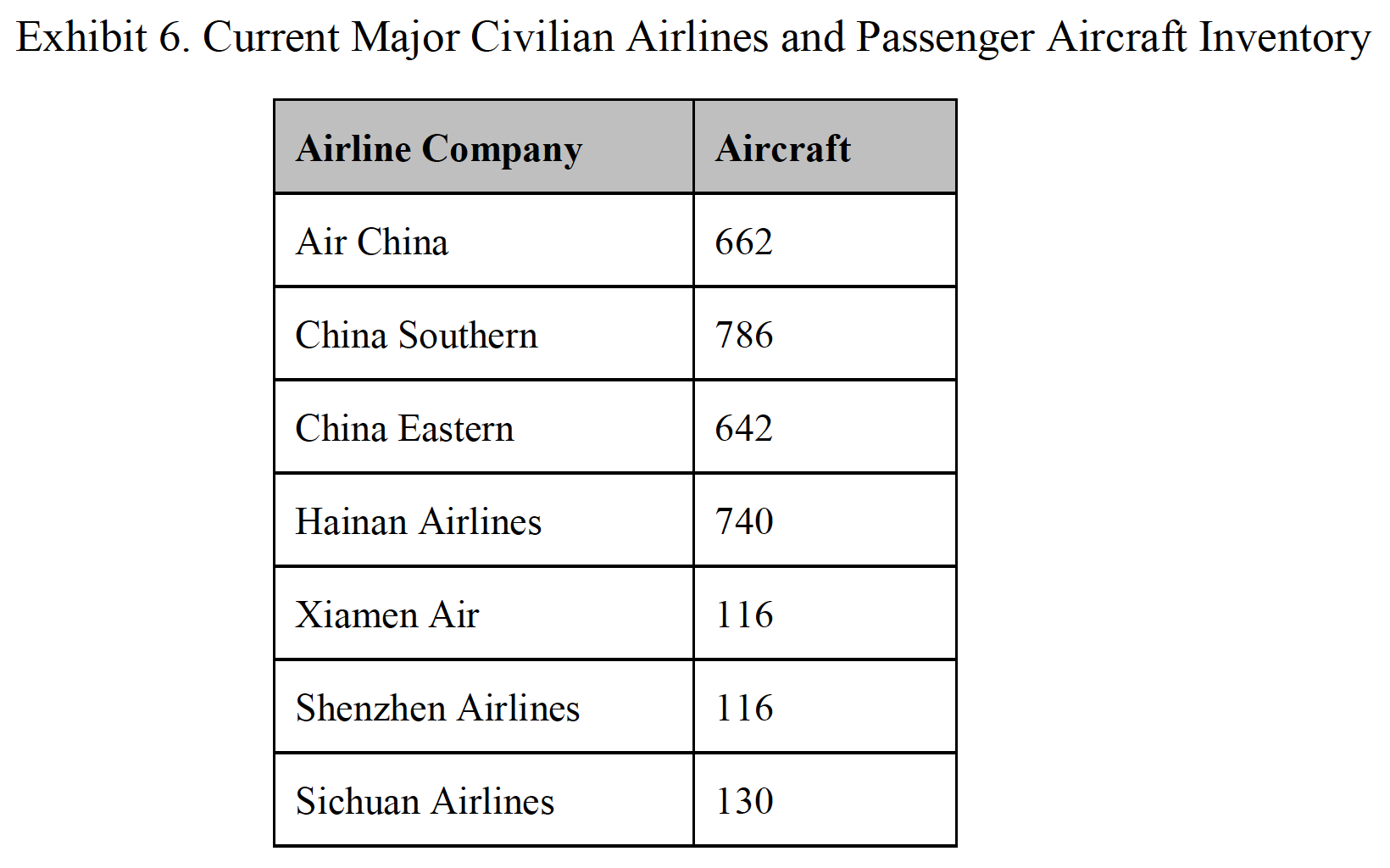

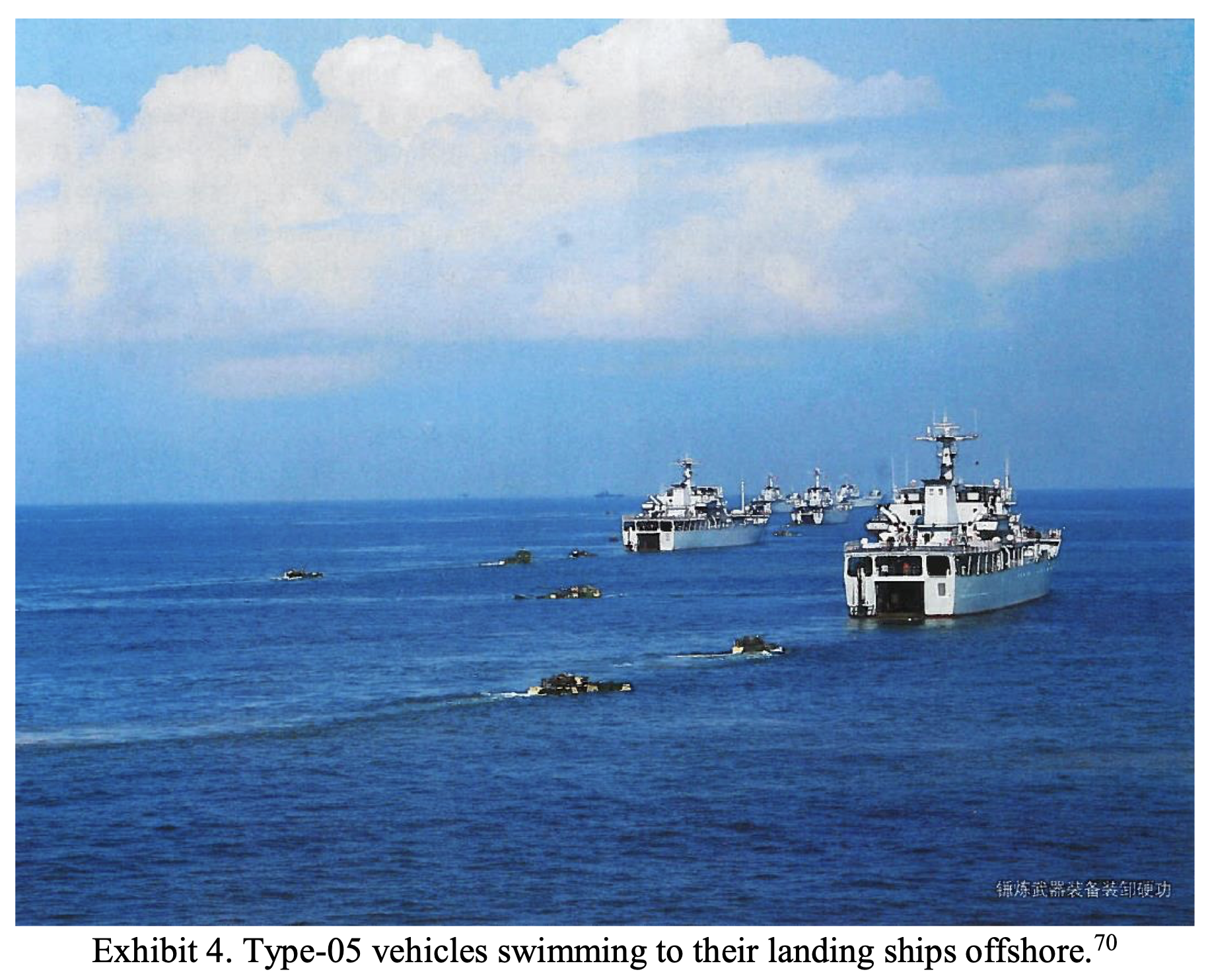

This CMR is the most comprehensive open source report anywhere detailing Chinese civilian shipping support to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) during 2023. Authored by Mike Dahm, this CMR is a follow-on to his previous CMR contributions including China Maritime Report No. 16 and China Maritime Report No. 25, which assessed PLA use of civilian shipping for logistics over-the-shore (LOTS) and amphibious landings between 2020 and 2022.

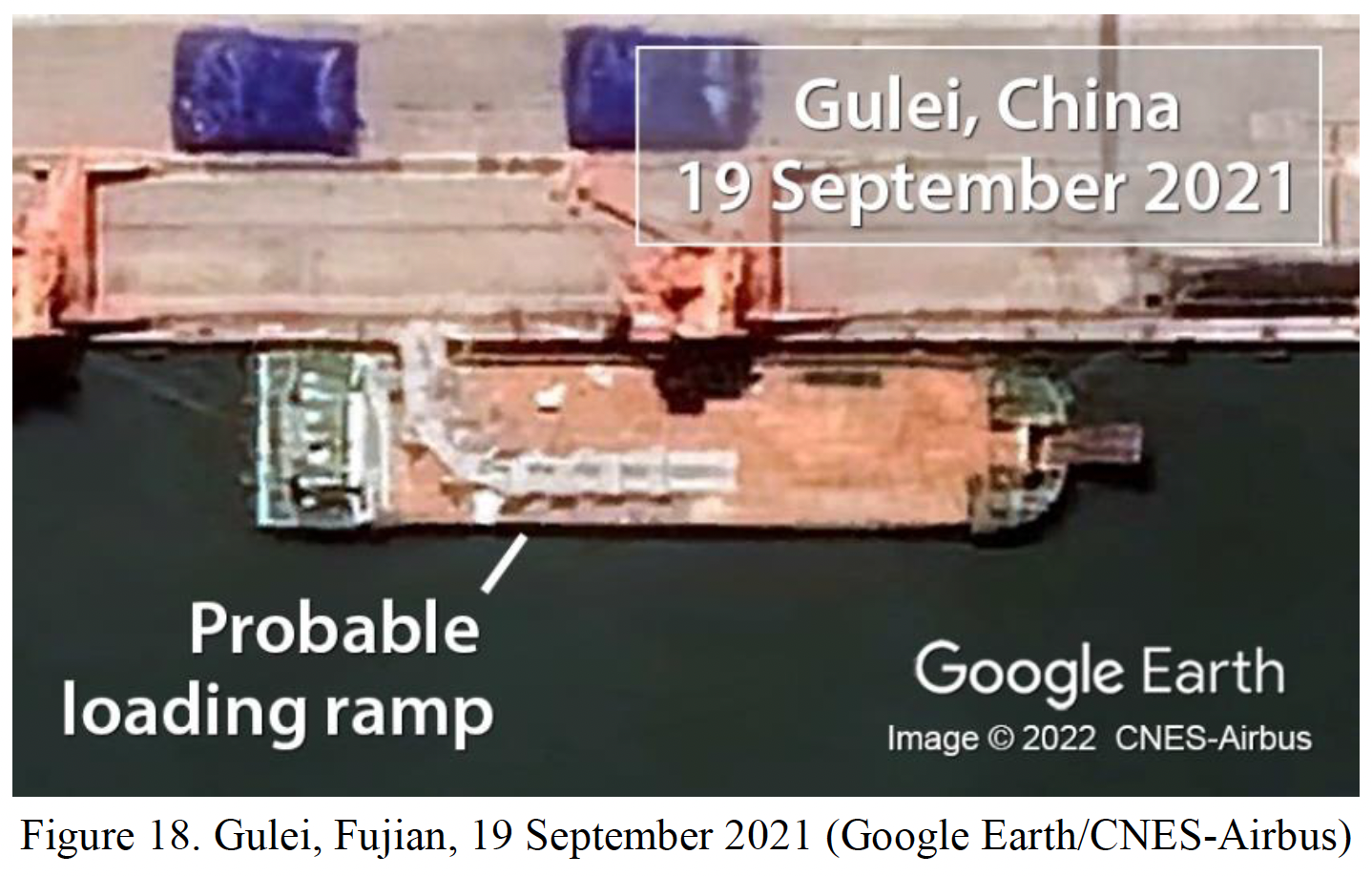

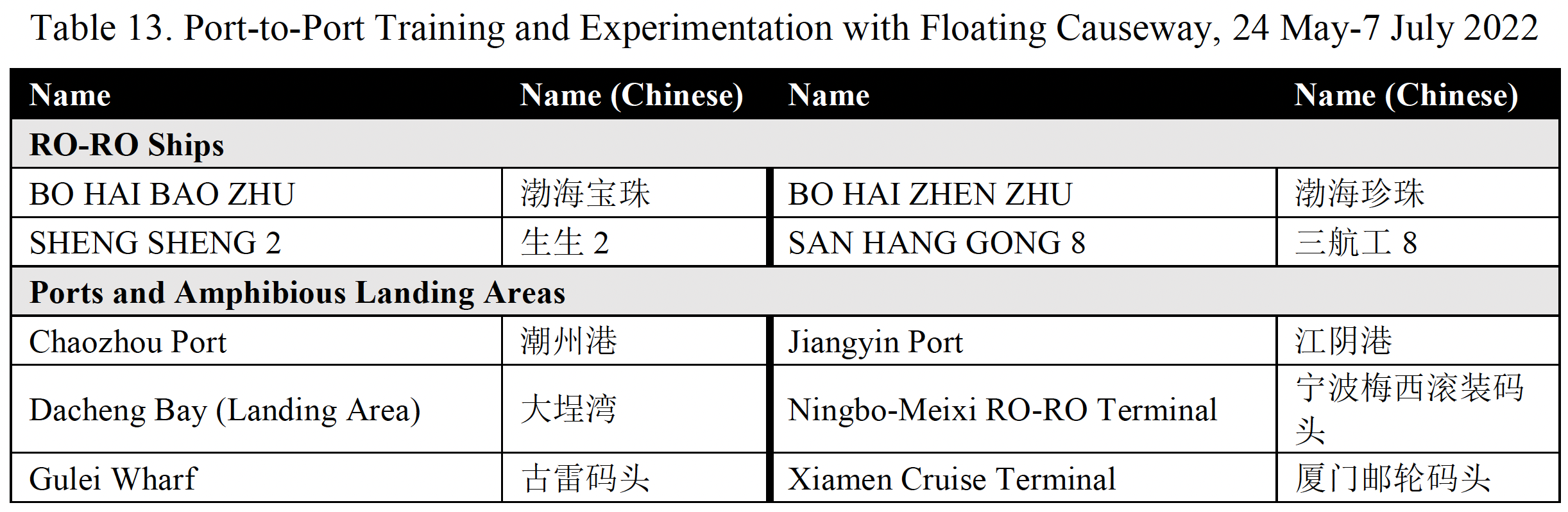

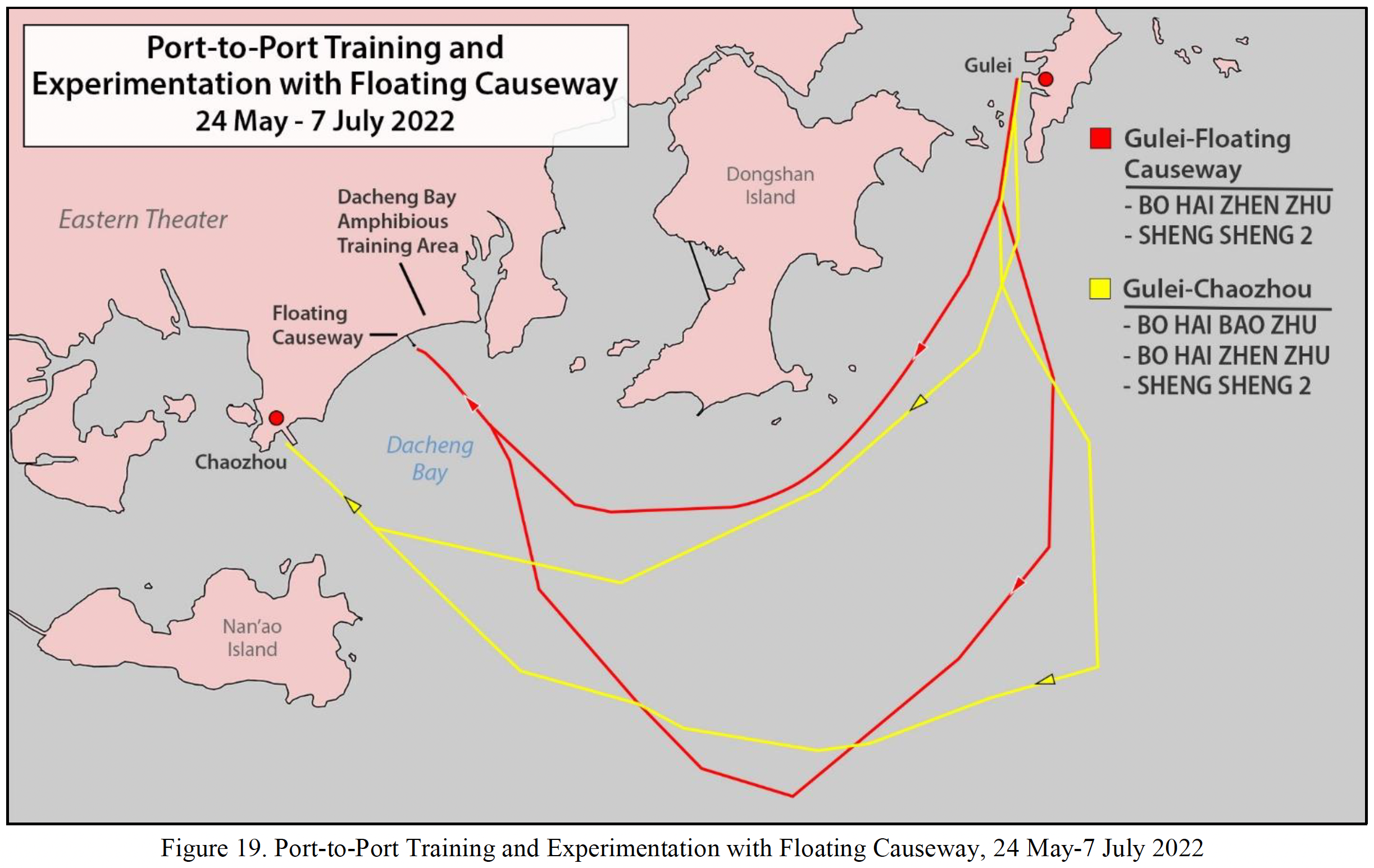

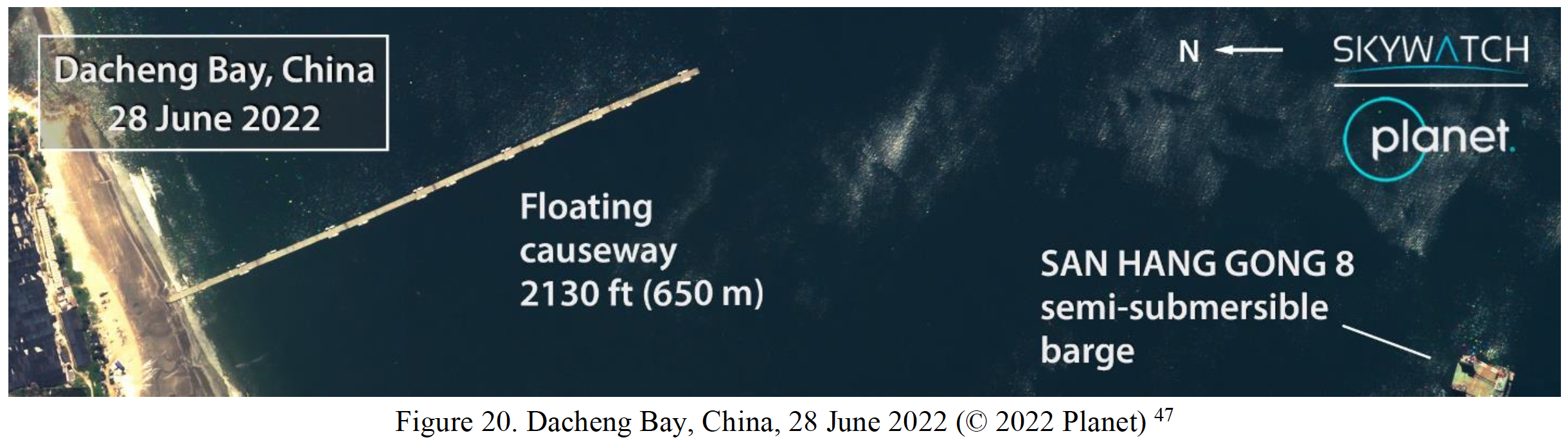

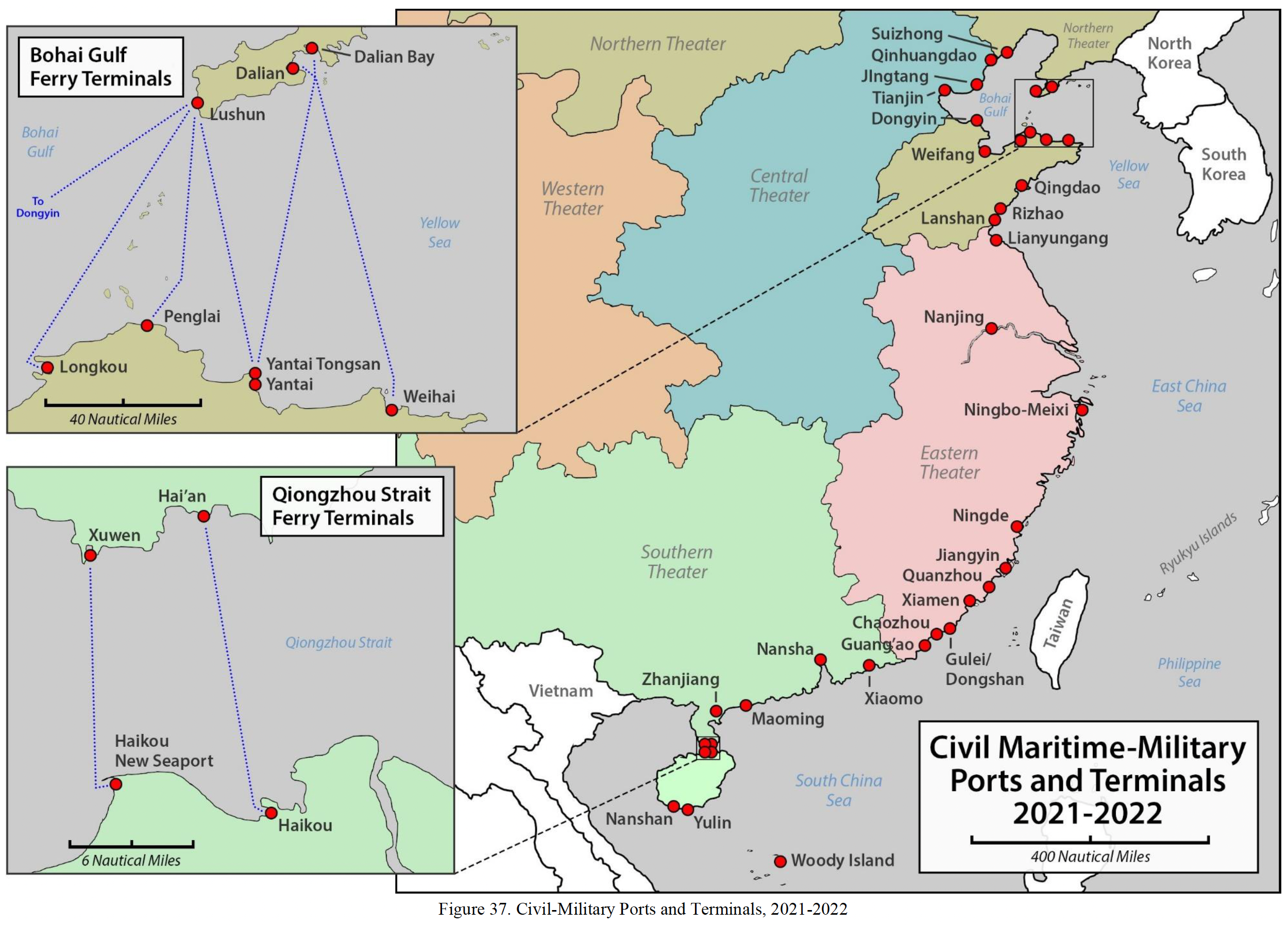

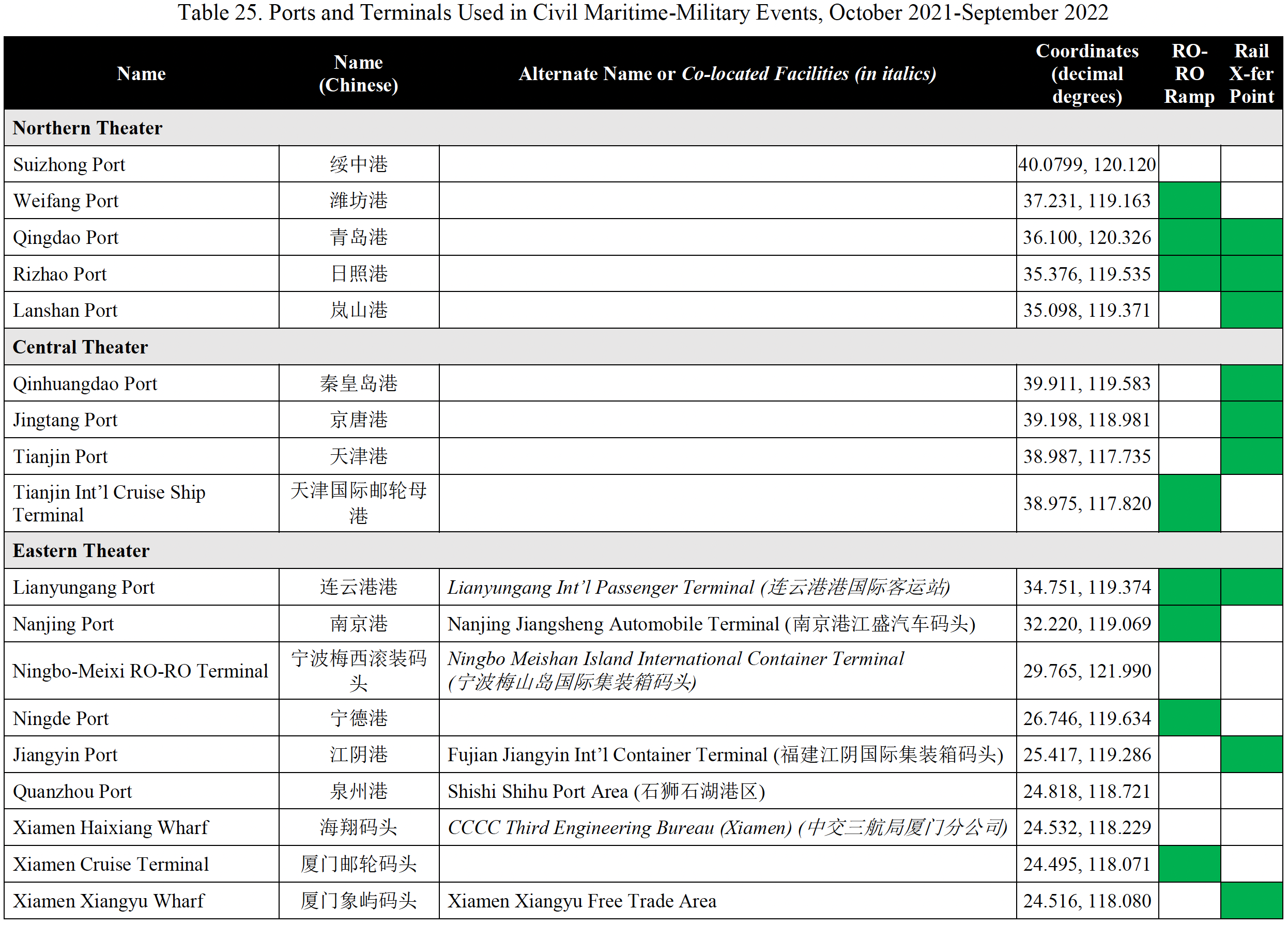

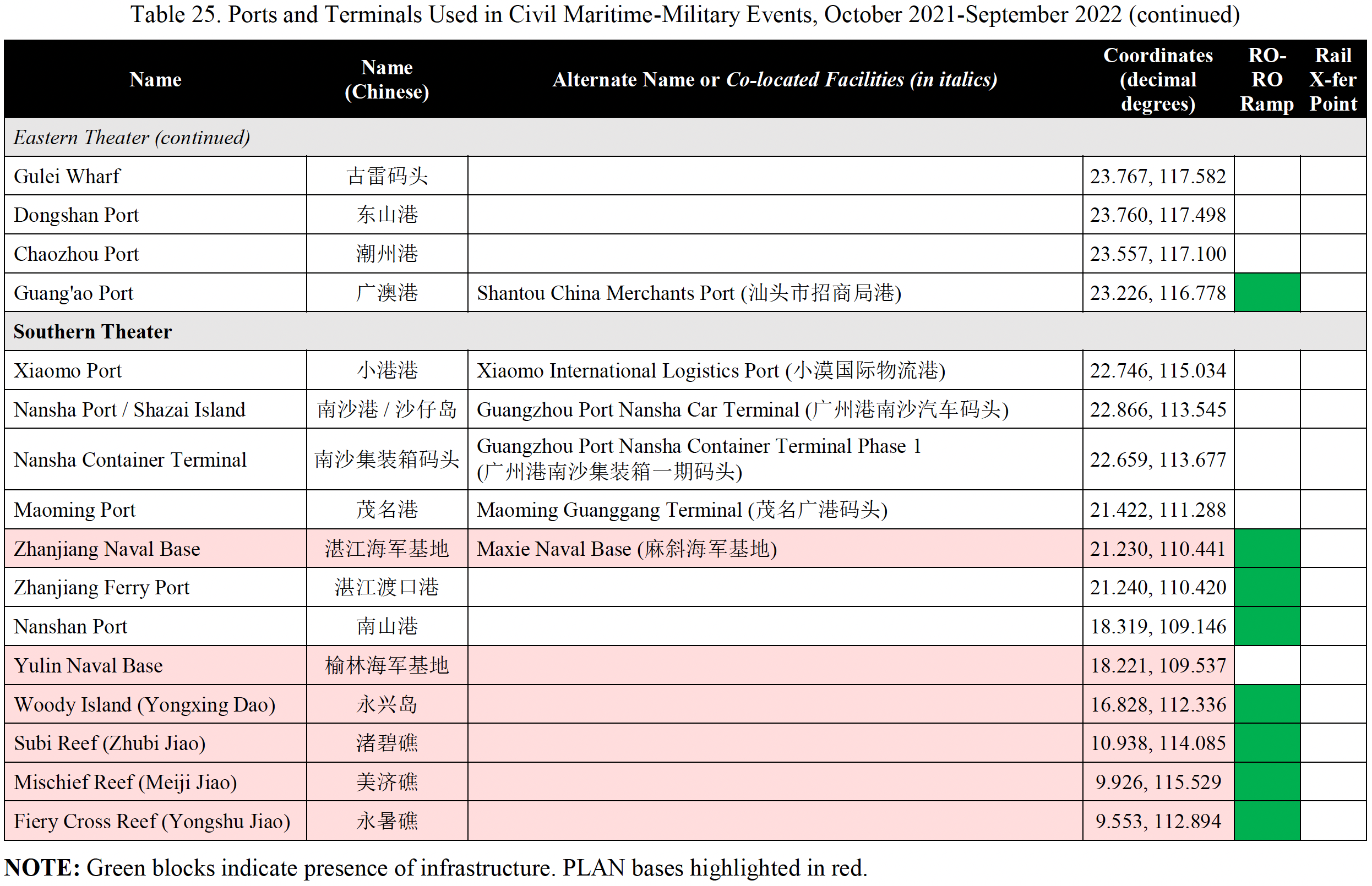

CMR #35, “Beyond Chinese Ferry Tales” highlights observed increases in inter-theater coordination including synchronized civil maritime military events across the PLA’s military theaters. It compliments information about deck cargo ships discussed in the just-published CMSI Note #4 published. It describes surge lift events involving roll-on/roll-off (RO-RO) ferries and identifies variable height loading ramps used by commercial vessels that may enable them to offload in ports regardless of tidal variations. Moreover, it provides imagery of a floating causeway system used to deploy forces to a beach landing area. There is much more critically useful information contained in this CMR.

One particularly noteworthy aspect of this particular CMR is that it contains dozens of tables, graphics, pictures, commercial imagery, and maps – to include a comprehensive listing of civilian/commercial ships observed supporting military events in 2023. The meticulous details compiled by Mr. Dahm makes it especially useful as a handy reference for all cross-Strait, PLA & China-Taiwan watchers.

Anyone interested in how the PLA integrates civilian maritime resources into PLA training will want to print this report and keep it handy.

About the Author

J. Michael Dahm is a retired U.S. Navy intelligence officer with 25 years of service. He is currently the Senior Resident Fellow for Aerospace and China Studies at the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies (https://mitchellaerospacepower.org/). He is also a lecturer at the George Washington University where he teaches a graduate course on China’s military. Before joining the Mitchell Institute, Dahm focused on intelligence analysis of foreign threats and defense technology for federally funded research and development organizations, the MITRE Corporation and the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. He has focused on Asia-Pacific security matters since 2006 when he served as Chief of Intelligence Plans for China and later established the Commander’s China Strategic Focus Group at the U.S. Pacific Command. From 2012-2015, he was an Assistant Naval Attaché at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing, China. Before retiring from the Navy in 2017, he served as Senior Naval Intelligence Officer for China at the Office of Naval Intelligence.

The author would like to thank the China Maritime Studies Institute’s Chris Sharman and Dr. Andrew Erickson for their encouragement to pursue this project and Ryan Martinson for his detailed editorial review and constructive recommendations. Finally, the author would like to express profound gratitude to his wife and children who tolerated this third annual “ferry hunt.”

This report reflects the analysis and opinions of the author alone. The author is responsible for any errors or omissions in this report.

Sources and Methods

This report fuses a variety of publicly and commercially available sources to gain detailed insights into often complex military activity and capabilities. Analysis is supported with AIS data from MarineTraffic—Global Ship Tracking Intelligence.112 The report features commercial satellite imagery from Planet Labs Inc. Medium-resolution satellite imagery from Planet’s PlanetScope constellation (ground sample distance (GSD) ~3.7 meters) was obtained through Planet’s Education and Research Program, which allows the publication of PlanetScope imagery for non-commercial research purposes.113 High-resolution satellite imagery from Planet’s SkySat constellation (GSD ~0.5 meters) was purchased by the author through SkyWatch Space Applications Inc. The report also features commercial satellite imagery from Airbus Intelligence. Images from Airbus’ Pleiades constellation (GSD ~0.5 meters) were also purchased by the author through SkyWatch Space Applications Inc.114 The SkyWatch team’s advice and assistance in accessing archived imagery was greatly appreciated. The author is responsible for all annotations of satellite images contained in this report. Planet and Airbus retain copyrights to the underlying PlanetScope, SkySat, and Pleiades images respectively. Satellite images published in this report should not be reproduced without the expressed permission of Planet or Airbus.

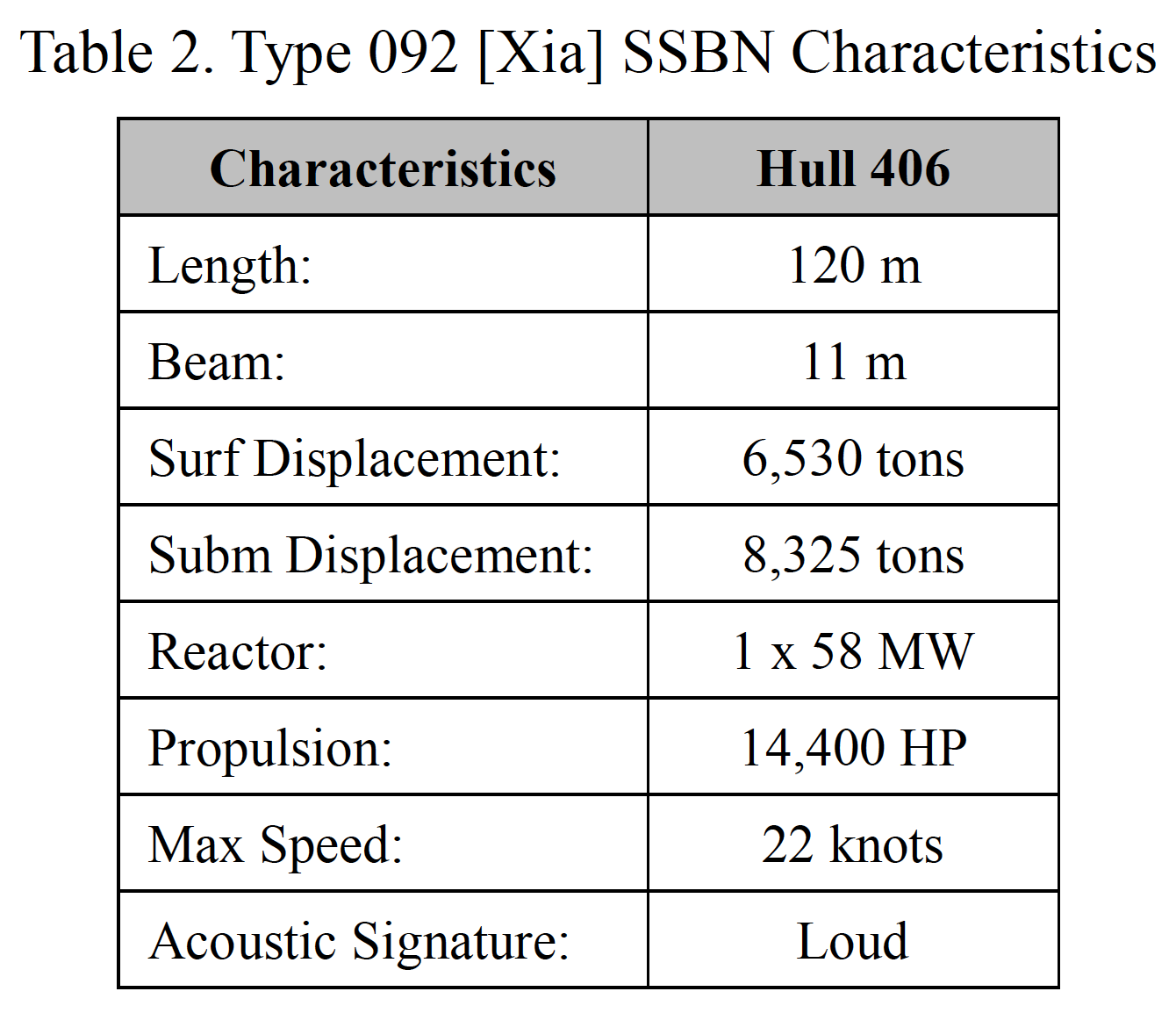

Summary

This report provides a comprehensive assessment of Chinese civilian shipping support to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), examining civil maritime-military activities in 2023. As of 2023 and probably through at least 2030, the PLA’s reserve fleet of civilian ships is probably unable to provide the amphibious landing capabilities or the over-the-shore logistics in austere or challenging environments necessary to support a major cross-strait invasion of Taiwan. However, 2023 activity has demonstrated significant progress toward that end. In addition to the extensive use of civilian ferries, this report identifies the first use of large deck cargo ships to support PLA exercises. While not as capable as large, ocean-going ferries, China’s civil fleet boasts dozens of large deck cargo ships and may provide the PLA with the lift capacity necessary to eventually support a large cross-strait operation. This report also discusses other civil maritime-military activities including “surge lift events,” coordination and synchronization of multi-theater events, floating causeway developments, and the dedicated use of civilian ships for intra-theater military logistics.

***

Christopher H. Sharman and Terry Hess, PLAN Submarine Training in the “New Era”, China Maritime Report 34 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, January 2024).

About the Authors

Captain Christopher H. Sharman, USN (Ret.) has served as the Director of the China Maritime Studies Institute since October 2023. He comes to CMSI following a 30-year active-duty Navy career that included diplomatic postings at U.S. Embassies in both China and Vietnam and multiple operational afloat assignments with the Japan-based Forward Deployed Naval Forces. His afloat assignments included tours aboard the USS Independence (CV 62), with the Strike Group Staff embarked aboard USS Kitty Hawk (CV 63), and with the Seventh Fleet Staff embarked aboard the USS Blue Ridge (LCC 19). He also served as a National Security Affairs Fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution. His military career culminated with his assignment to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence as the Senior Strategist for the National Intelligence Manager for East Asia with responsibilities for synchronizing the Intelligence Community’s China efforts. He has written numerous articles for various journals, is a frequent podcast guest, and published a monograph through the Institute of National Strategic Studies titled, China Moves Out: Stepping Stones Toward a New Maritime Strategy.

Mr. Terry Hess is a U.S. Navy submarine warfare analyst with more than ten years’ experience developing methodologies and assessments of submarine warfare concepts. He is a retired USN Senior Chief Acoustic Intelligence (ACINT) Specialist with multiple years of operations at sea including an overseas assignment in Sydney, Australia. Hess served aboard three fast attack submarines: the USS Richard B. Russell (SSN-687), USS La Jolla (SSN-701), and USS Parche(SSN-683). He has been married for 32 years to Kathryn Hess with three adult children and seven grandchildren living throughout the United States. Hess has a passion for submarine warfare research and novel concepts of capability employment.

Summary

Since 2018, there have been significant changes to People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) submarine force training, and these changes have been driven by important revisions to strategic guidance and subsequent directives that focused PLA efforts to enhance its capabilities to operate in the maritime domain. While this guidance is applicable to all services, improving PLAN submarine force capabilities appears to have been of particular interest to senior Chinese leadership. This guidance expanded the PLA’s maritime domain requirements, which demanded that China’s submarine force improve its capabilities to operate independently or along with other PLAN assets at greater distances from coast and in the far seas. This has resulted in submarine training that is more realistic, rigorous, and standardized across the fleet. Though stressful on submarine equipment and crews, these changes to training may ultimately yield a more combat-capable submarine fleet operating throughout the western Pacific.

Introduction

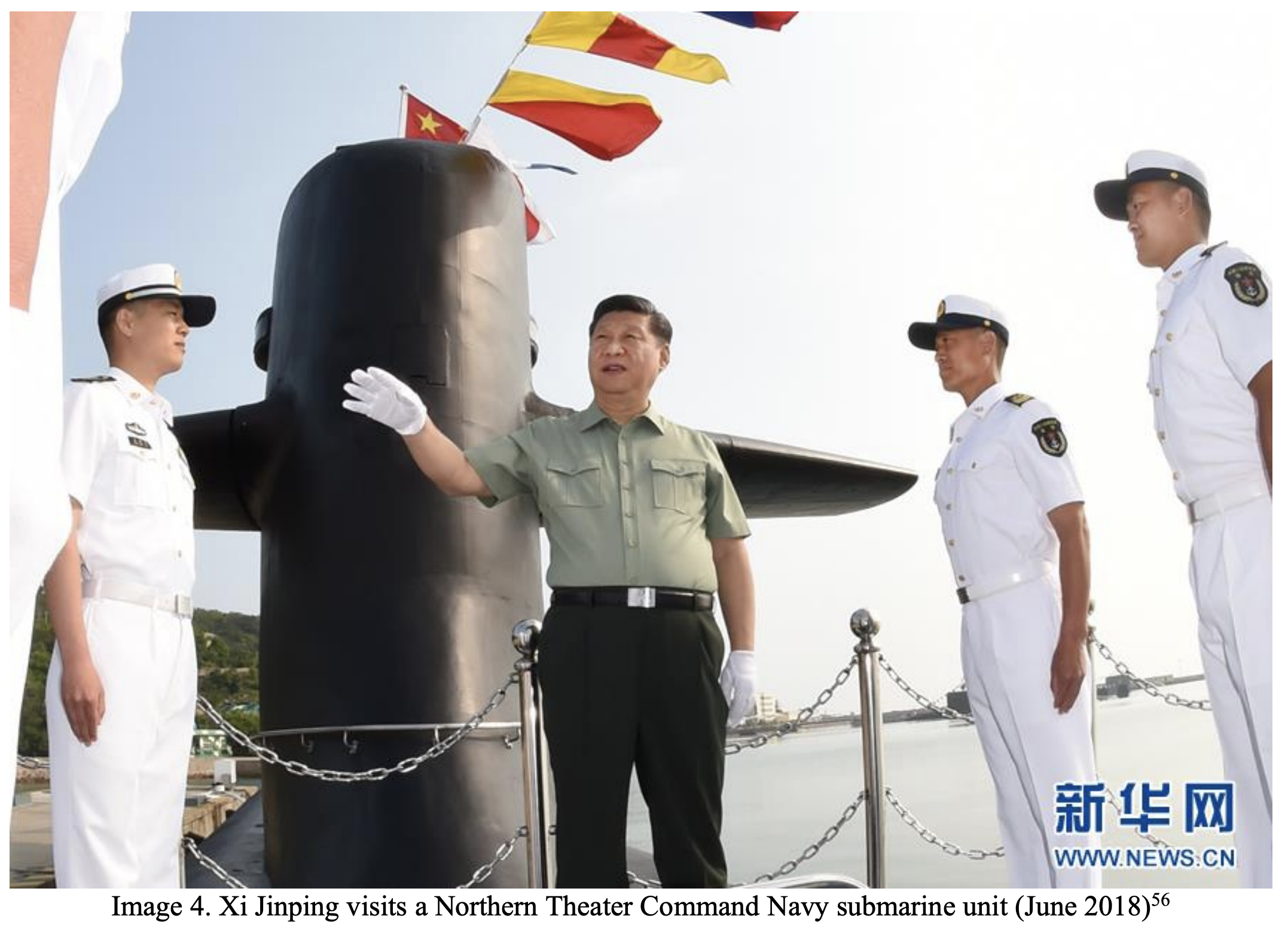

On the afternoon of June 11, 2018, People’s Republic of China (PRC) President and Central Military Commission (CMC) Chairman, Xi Jinping, climbed through the hatch of a Type 093 (Shang class) submarine moored at Qingdao Submarine Base—his second visit aboard a People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) nuclear submarine since assuming his role as CMC Chairman in November 2012. While aboard, he encouraged the crew to “train to excel in the skills for winning.”1 After disembarking, he toured the comprehensive simulation building at the nearby PLAN Northern Theater Command Headquarters, where he learned how simulator improvements helped make submarine training more realistic. His day culminated with a speech to the assembled PLAN leadership, where he stated:

It is necessary to earnestly implement the new generation of military training regulations and military training programs, increase the intensity of training, innovate training modules, and strictly strengthen the supervision of training. It is necessary to launch mass training exercises in the new era, strengthen targeted training, training in actual cases, and training for commanders, and strengthen military struggle for frontline training [sic].2

While Xi could have delivered his remarks to an army unit or issued guidance through a written order from Beijing, his itinerary and comments suggest his visit was deliberately choreographed to convey a strategic focus on training—and that submarine training was of particular interest to the highest levels of PLA leadership.

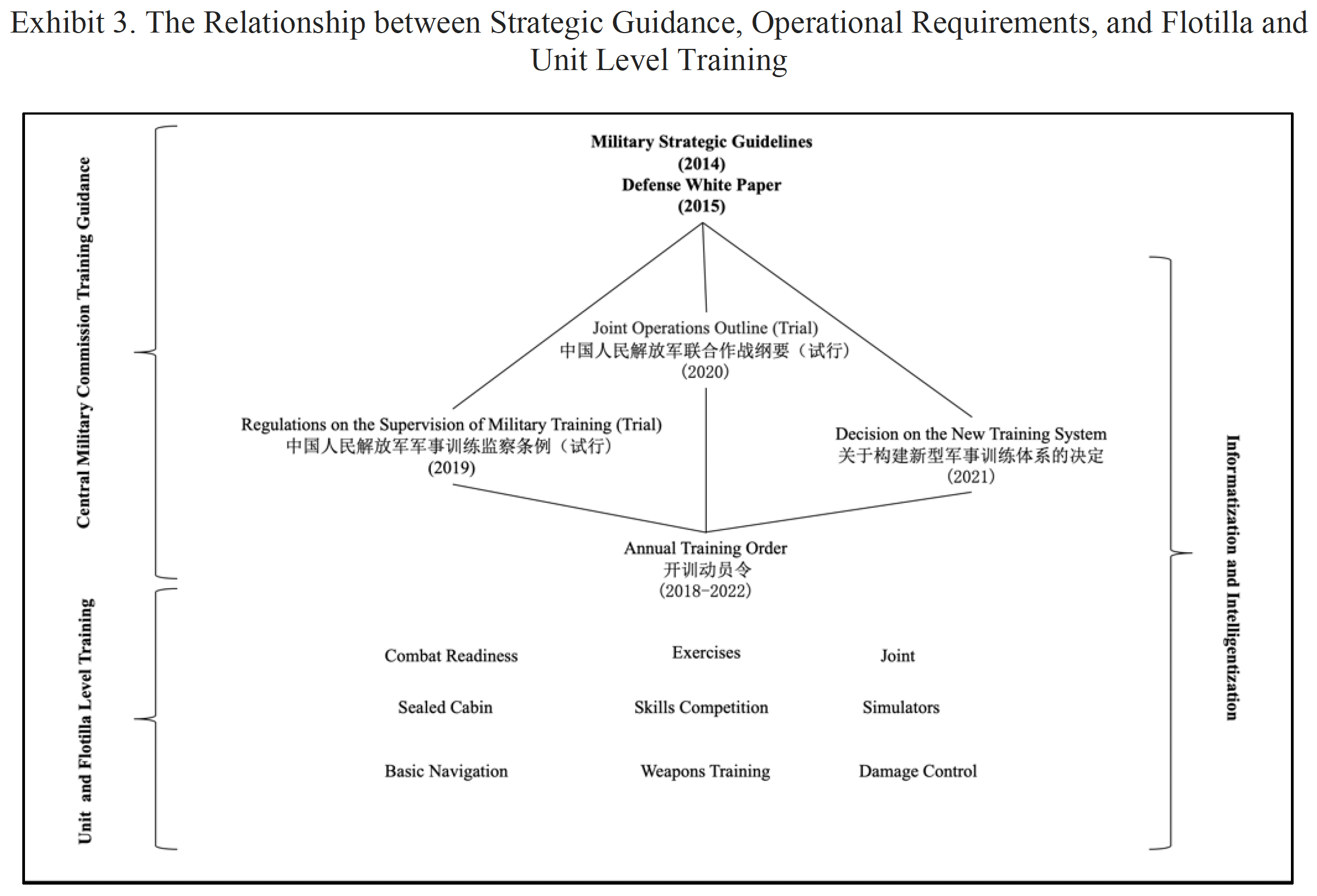

Xi’s direction to improve training was not new, but a continuation of previous strategic guidance. For instance, the 18th Party Congress work report issued in November 2012 highlighted the need to “revitalize the research style of combat problems and strengthen practical training.”3 Rather, Xi’s June 2018 speech reflects a renewed CMC emphasis on PLA training in order to advance capabilities necessary to address additional operational requirements driven by changes in strategic guidance. This report argues that the PLA began a concerted effort to adopt new tactical and operational concepts to address these requirements starting in 2018 and that these efforts have significant implications for submarine doctrine and how the submarine force trains. … … …

Conclusion

The PLAN submarine force is rapidly adapting to CMC training directives and requirements issued since 2018 to support the changes to the 2014 military strategic guidelines. In alignment with this guidance, submarines are training more regularly under realistic combat conditions for longer durations while operating under informatized conditions at greater distances from the PRC coast. The submarine force is developing innovative tactics, incorporating intelligentization, and progressing toward the capability to conduct integrated joint operations. Commentary by PLA authors, however, suggests integrated joint operations remain aspirational. While the individual services may operate in proximity to each other during large- and small-scale training exercises, coordination at the unit-level appears primarily to be between units within the same service. Meanwhile, as the PLAN integrates new platforms and technologies into its inventory, crews must also become familiar with the new equipment and develop numerous basic skills necessary to operate a submarine safely at sea.

The multitude of training requirements promulgated since 2018 places tremendous stress on both crews and equipment. The physical stress on equipment and mental strain on submarine crews increases the likelihood of an equipment failure or human error that could result in a catastrophic disaster. Ironically, such an incident could undermine CMC confidence in the submarine force’s ability to execute critical missions, jeopardizing the PRC’s prospects for “national rejuvenation”—a likely reason the CMC adjusted its strategic guidelines in 2014 and issued follow-on training guidance starting in 2018.

On the other hand, it has been just five years since the CMC began issuing annual training orders. In this short time, the submarine force has implemented protocols that help to ensure training is similar to combat while crews are ashore, pier side, and at sea. Should the submarine force continue on its current training trajectory and improve its intelligentization by integrating new technologies such as AI and improved tactical communications systems, PLAN submarines will be more capable of executing combat operations throughout the near and far seas and present a more potent threat across the western Pacific.

***

David C. Logan, China’s Sea-Based Nuclear Deterrent: Organizational, Operational, and Strategic Implications, China Maritime Report 33 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, December 2023).

About the Author

Dr. David C. Logan is Assistant Professor of Security Studies at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. His research focuses on nuclear weapons, arms control, deterrence, and the U.S.-China security relationship. He previously taught in the National Security Affairs Department at the Naval War College and served as a Stanton Nuclear Security Fellow with the MIT Security Studies Program and a Fellow with the Princeton Center for International Security Studies, where he was also Director of the Strategic Education Initiative. Dr. Logan has conducted research for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs at National Defense University, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, and the Office of Net Assessment. He has published in International Security, Journal of Strategic Studies, Georgetown University Press, National Defense University Press, Foreign Affairs, Los Angeles Times, and War on the Rocks, among other venues. He holds a B.A. from Grinnell College and an M.P.A., M.A., and Ph.D. from Princeton University.

The author wishes to thank Tom Stefanick, Liza Tobin, CDR Robert C. Watts IV, and the members of the China Maritime Studies Institute for helpful comments on earlier versions of this report.

Summary

China’s development of a credible sea-based deterrent has important implications for the PLAN, for China’s nuclear strategy, and for U.S.-China strategic stability. For the PLAN, the need to protect the SSBN force may divert resources away from other missions; it may also provide justification for further expansion of the PLAN fleet size. For China’s nuclear strategy and operations, the SSBN force may increase operational and bureaucratic pressures for adopting a more forward-leaning nuclear strategy. For U.S.-China strategic stability, the SSBN force will have complex effects, decreasing risks that Chinese decisionmakers confront use-or-lose escalation pressures, making China less susceptible to U.S. nuclear threats and intimidation and therefore perceiving lower costs to conventional aggression, and potentially introducing escalation risks from conventional-nuclear entanglement to the maritime domain.

Introduction

China is undertaking a significant nuclear expansion and modernization. While China’s nuclear warhead stockpile numbered fewer than 300 bombs just a few years ago, the Department of Defense estimates that by 2030 the “the PRC will have about 1,000 operational nuclear warheads, most of which will be fielded on systems capable of ranging the continental United States (CONUS)” and could have as many as 1,500 warheads by 2035.”1 While the changes within the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force (PLARF) have received significant attention, the development of a credible fleet of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) will also have important implications for China’s nuclear strategy and operations, the PLA Navy (PLAN), and U.S.-China strategic stability. Given the deterioration of U.S.-China relations, growing competition in the nuclear domain, and the prominence of the maritime domain to any future U.S.-China crisis or conflict, China’s SSBN force will assume greater importance. This report examines these developments and their implications.

China’s development of its first credible sea-based nuclear deterrent has several implications for China’s naval force structure and strategy, Chinese nuclear strategy and operations, and U.S.-China strategic stability. For the PLAN, a sea-based nuclear deterrent will likely impose new demands on the rest of the navy by requiring the service to dedicate other forces to the defense of SSBNs and may require the PLAN to develop personnel reliability and warhead handling programs, which could lead to changes from its historically centralized approach to nuclear weapons. For China’s nuclear strategy and operations, the realization of a full nuclear triad may lead the PLA to construct bodies and processes for maintaining real-time awareness of the status of China’s nuclear deterrent, and for targeting coordination and deconfliction among the nuclear capabilities of the PLARF, the Navy and the Air Force. The SSBN force may also require the establishment and empowerment of additional nuclear constituencies within the PLA, which might advocate for a greater role for nuclear weapons in China’s national security strategy, while the operational requirements of an SSBN force may encourage China to reconsider some of its longstanding nuclear weapons practices. Finally, for U.S.-China strategic stability, the development of a credible sea-based deterrent, to the extent it strengthens Chinese decisionmakers’ confidence in the survivability of the country’s nuclear deterrent, may strengthen some forms of crisis stability while weakening others, provide Beijing the option to use its stronger nuclear forces as a shield behind which to initiate conventional aggression, and introduce new forms of inadvertent escalation stemming from conventional-nuclear “entanglement.”

This report draw on a wide-range of sources.2 It prioritize sources traditionally viewed as authoritative, including China’s Defense White Papers, high-level curricular materials published by PLA research institutions, such as the Science of Military Strategy volumes published by the Academy of Military Science and National Defense University, and academic writings published by researchers affiliated with PLA institutions, including both the PLAN Submarine Academy and the Rocket Force Engineering University.3 This report also reviews articles appearing in major Chineselanguage venues, particularly those published by influential think tanks and research centers.4 This report examines military reporting and commentary as well as secondary sources discussing Chinese views of strategic stability. Finally, it draws on U.S. sources, including unclassified U.S. intelligence estimates and public assessments from the Department of Defense, as well as public statements from senior U.S. military officials. One caveat on any open-source analysis of Chinese nuclear views is the limits created by the historical division between China’s strategic community, consisting of researchers and strategists at civilian and PLA-affiliated institutions, and the operator community, consisting of the military professionals in the PLA and, specifically, the missile forces charged with operating the country’s nuclear missiles.5 The views of the strategic community are more accessible than those of operators. However, as of the early 2000s, there were signs of greater interaction between these two communities, including strategists briefing operators, operators pursuing Ph.Ds. at civilian institutions, and participation by operators in Track-1.5 dialogues with American colleagues.6

The report proceeds in five parts. First, it summarizes key features of China’s SSBN force, including recent developments, technical capabilities, and operational practices. Second, it reviews potential implications of the SSBN force for the PLAN, including naval force development and force allocation. Third, it assesses implications for China’s nuclear strategy and operations, including the unique role of the SSBN force within China’s nuclear deterrent and the pressures the force may create for China to change its nuclear operations and strategy. Fourth, it reviews implications of the SSBN force for U.S.-China strategic stability. Finally, it concludes with a discussion of implications for U.S. policy and future research on China’s nuclear forces.

Conclusion

China’s development of a credible sea-based deterrent has important implications for the PLAN, for China’s nuclear strategy, and for U.S.-China strategic stability. For the PLAN, the need to protect the SSBN force may divert resources away from other missions; it may also provide justification for further expansion of the PLAN fleet size.83 For China’s nuclear strategy and operations, the SSBN force may increase operational and bureaucratic pressures for adopting a more forward-leaning nuclear strategy. For U.S.-China strategic stability, the SSBN force will have complex effects, decreasing risks that Chinese decisionmakers confront use-or-lose escalation pressures, making China less susceptible to U.S. nuclear threats and intimidation and therefore perceiving lower costs to conventional aggression, and potentially introducing escalation risks from conventional-nuclear entanglement to the maritime domain.

The findings reported here have important implications for both U.S. policy and for future research on the PLA. First, the U.S. Navy and intelligence community should identify and assess the escalation risks stemming from conventional-nuclear entanglement at sea. U.S. decisionmakers and operational plans must account for these risks. Addressing the risks may require tradeoffs between maximizing conventional advantages and limiting the risks of nuclear use by, for instance, limiting ASW against Chinese SSBNs and supporting capabilities. Second, possible nuclear arms control agreements between China and the United States must account for other legs of the Chinese deterrent. While the current poor state of U.S.-China relations makes near-term arms control unlikely, decision makers can lay the foundation now for future agreements.84 Proposals for U.S.- China arms control have largely focused on China’s land-based missiles.85 However, potential arms control efforts will need to consider how to incorporate the specific challenges of other legs of a Chinese nuclear triad. Third, the U.S. Navy will have to weigh the costs, benefits, and risks of allocating military assets to either the strategic ASW mission targeting Chinese SSBNs or to conventional military operations.86 In a crisis or conflict, tracking or targeting Chinese SSBNs might provide the United States coercive leverage or help support a damage limitation nuclear strategy, but it would reduce the resources available for other missions and might be viewed as an escalatory attempt to undermine China’s strategic deterrent. Finally, China analysts may need to increasingly consider domestic, non-strategic drivers of the country’s nuclear strategy and operations. While China’s nuclear strategy likely remains sensitive to U.S. policy choices, factors rooted in bureaucratic posturing, domestic politics, and international prestige may become increasingly important for Beijing. It may be more challenging for the United States to influence these factors.

***

Joshua Arostegui, The PCH191 Modular Long-Range Rocket Launcher: Reshaping the PLA Army’s Role in a Cross-Strait Campaign, China Maritime Report 32 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, November 2023).

About the Author

Joshua Arostegui is the Chair of China Studies and Research Director of the China Landpower Studies Center at the U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute. His primary research topics include Chinese strategic landpower, People’s Liberation Army joint operations, and Indo-Pacific security affairs. Mr. Arostegui previously served as a Department of the Army Senior Intelligence Analyst for China. He is also a Chief Warrant Officer 5 in the U.S. Navy Reserve where he serves as a technical director in the Information Warfare Community. Mr. Arostegui earned a M.A. in International Relations from Salve Regina University and a M.A. in History from the University of Nebraska, Kearney. He is also a graduate of the U.S. Marine Corps Command and Staff College Distance Education Program and the Defense Language Institute’s Basic and Intermediate Chinese Courses. The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. The author would like to thank Dennis Blasko and James McNutt for their insight and recommendations, as well as Ryan Martinson for his editorial review.

Summary

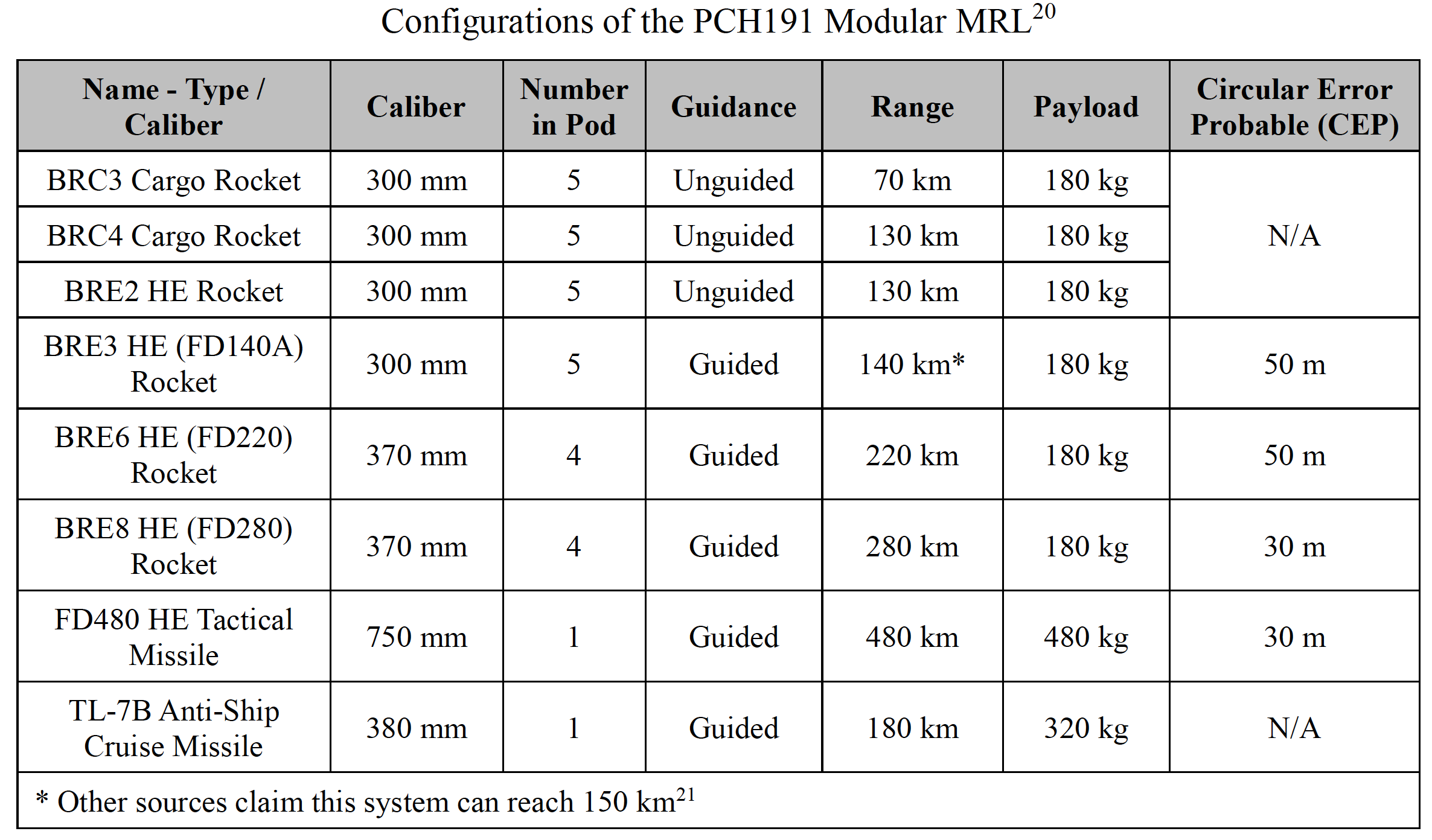

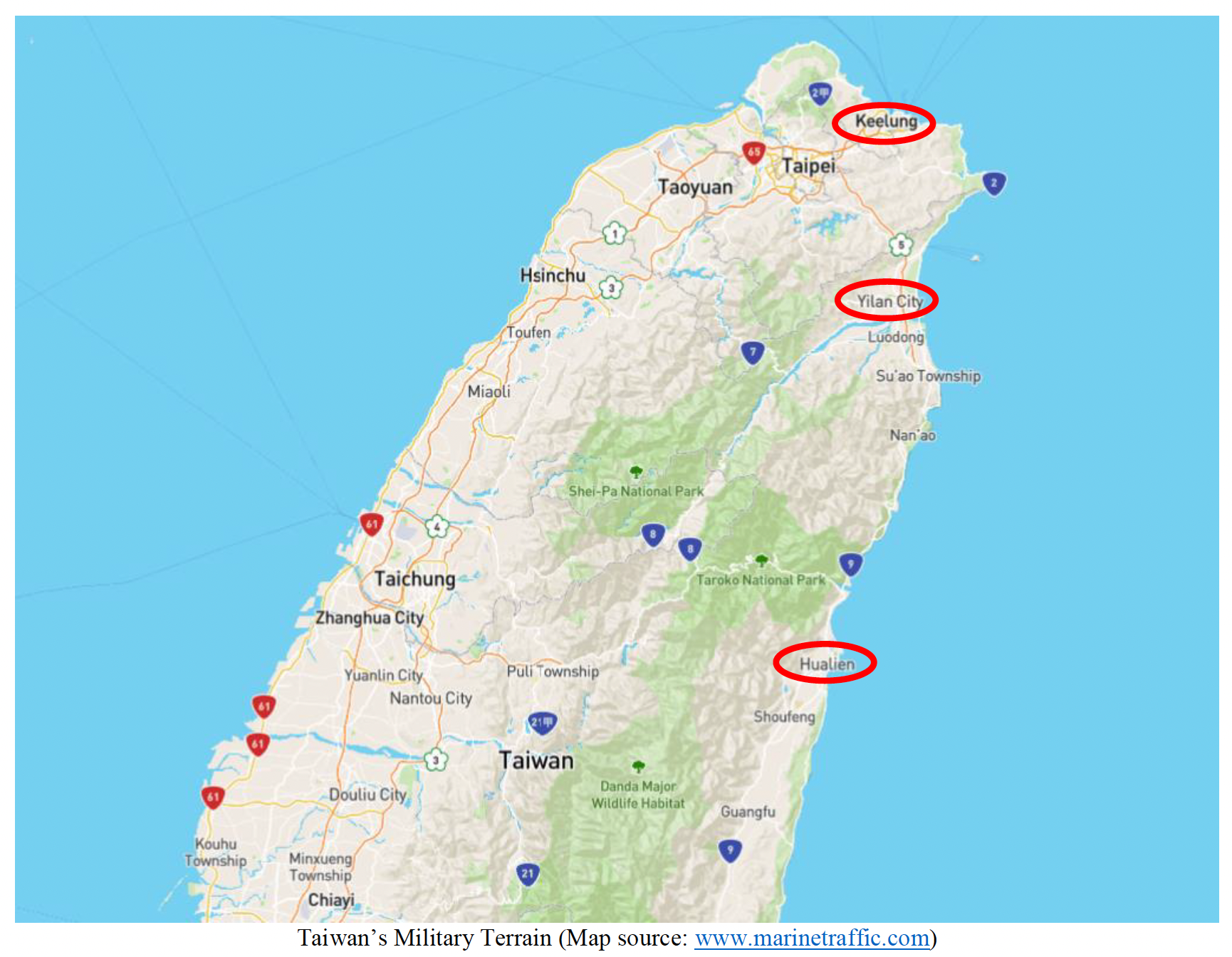

With its fielding of the PCH191 multiple rocket launcher (MRL) and its variety of long-range precision munitions, the PLA Army (PLAA) has become arguably the most important contributor of campaign and tactical firepower during a joint island landing campaign against Taiwan. No longer simply the primary source of amphibious and air assault forces, the PLAA is now capable of using its multiple battalions of PCH191 MRLs to support maritime dominance, the joint firepower strike, and ground forces landing on Taiwan’s shores and in depth. The Chinese ordnance industry has developed multiple low-cost rockets, an anti-ship cruise missile, and a tactical missile to be used with the PCH191, as well as its export variant, the AR3, including munitions that can quickly and precisely strike targets in the Taiwan Strait, across the island, and beyond. Recent demonstrations of the PCH191 during PLA training events and Eastern Theater Command response actions to politically charged visits, in addition to the fielding of new reconnaissance assets capable of providing targeting and battle damage assessments to the MRL, make it clear the Army intends to use the system to achieve effects in a future Taiwan crisis that formerly would have been the responsibility of other PLA services.

Introduction

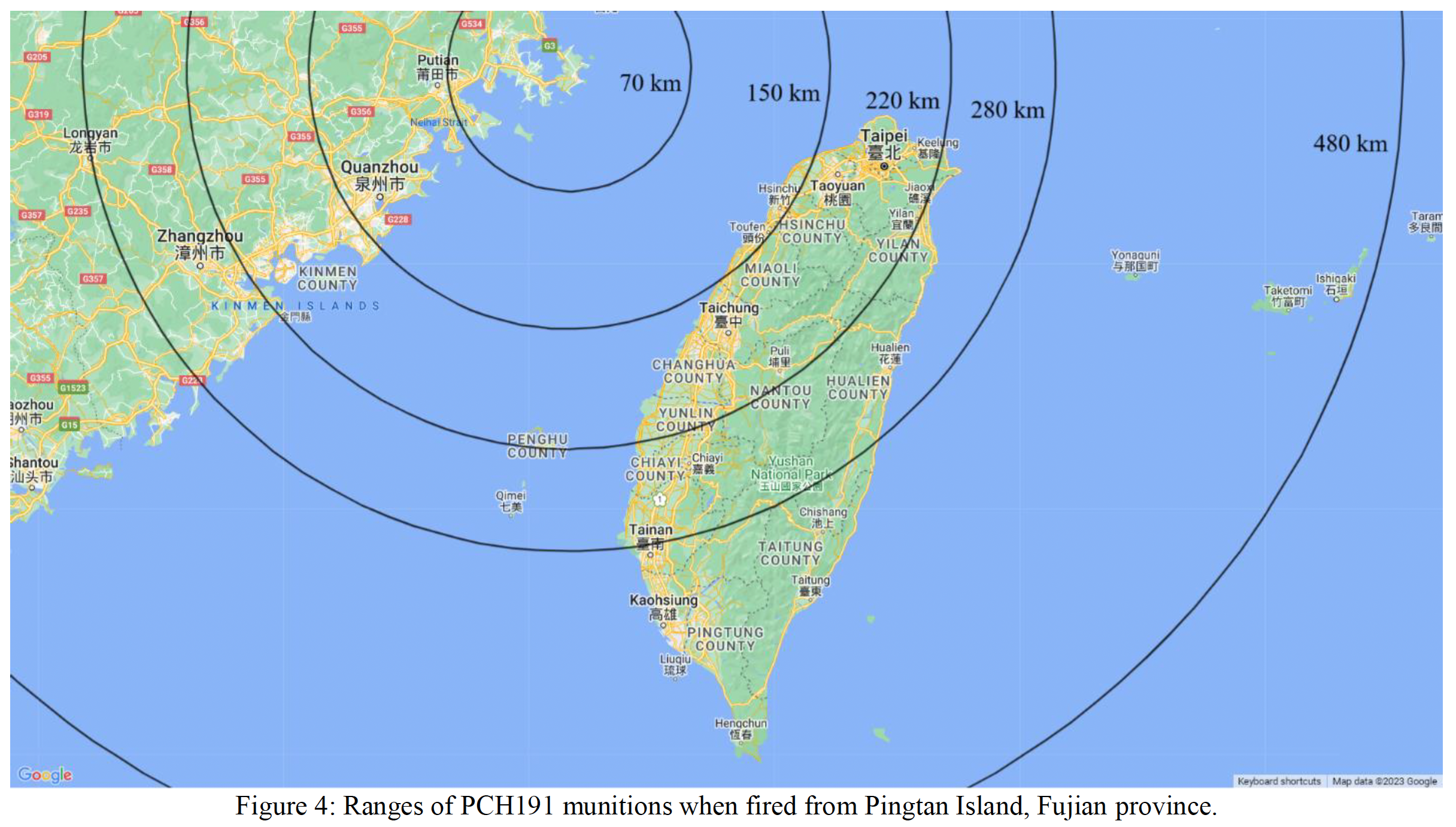

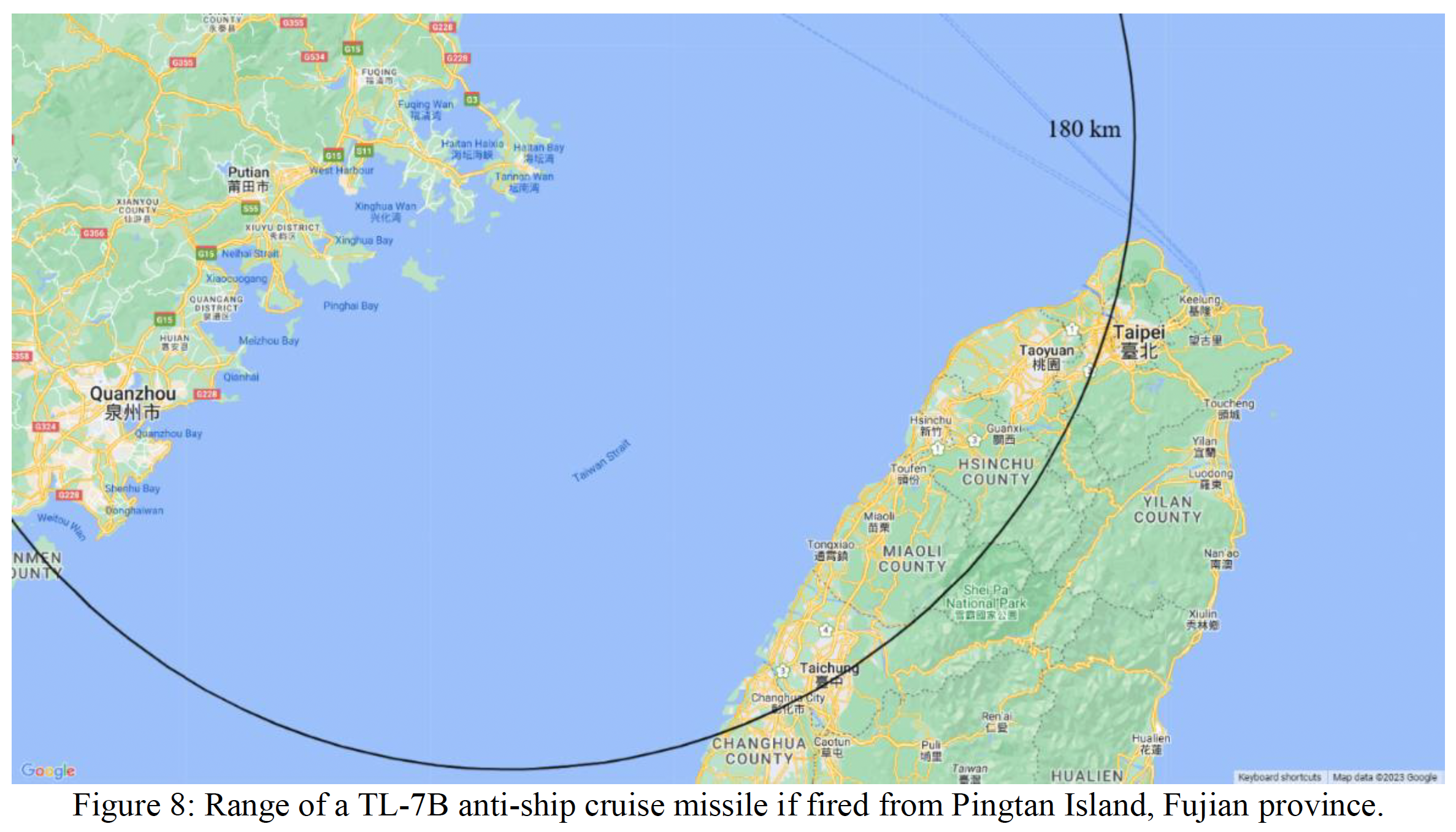

On August 4, 2022, the Chinese PLA Army (PLAA) used three of its new modular long-range multiple rocket launcher (MRL) systems, the PCH191, in the large joint exercise in response to U.S. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan. The PLA dispatched launchers from the 72nd Artillery Brigade, 72nd Group Army, PLA Eastern Theater Command (ETC) Army, to Pingtan Island, Fujian province—the narrowest point in the Taiwan Strait (approximately 150 km from Taoyuan Airport on Taiwan’s western shore). There, each launcher fired an unknown number of rockets into a designated zone that stretched from off China’s coast beyond the median line in the Taiwan Strait.1 Although the rocket launches received some coverage from official People’s Republic of China (PRC) media outlets, the focus remained on the much more provocative PLA Rocket Force (PLARF) missiles fired over Taiwan, as well as the large number of PLA Navy (PLAN) and PLA Air Force (PLAAF) platforms patrolling around the island.

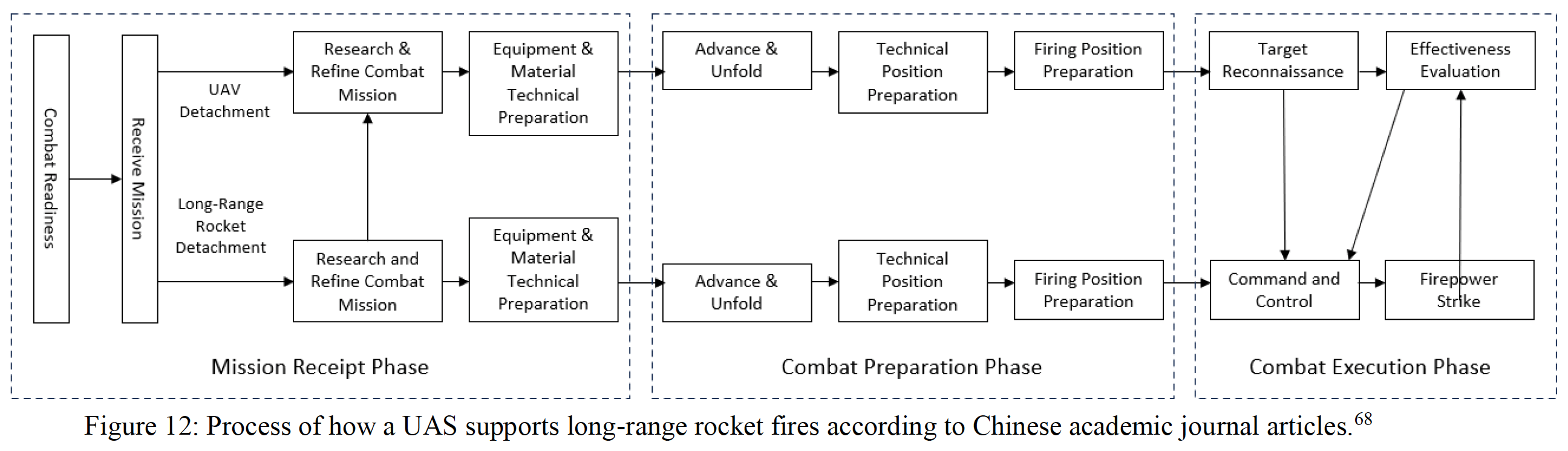

Yet the introduction of the PCH191 should not be overlooked.2 It marks a major advance in the PLAA’s potential contributions to a cross-strait invasion. While the Army traditionally had the lead in landing on the island and seizing key strategic points during a potential Taiwan invasion campaign, China’s primary ground force only had limited capabilities to affect the battlefield prior to landing. Once on the island, its armor and infantry forces would have to rely heavily on the joint services to protect their troops on the beaches and in-depth because it lacked the organic weapons to execute those fire support missions. The range and precision of the PCH191 now allows the PLAA to quickly execute these missions out to ranges nearing 500 km. Moreover, it can provide those same capabilities to assist its sister services by striking air and coastal defense missile systems, sea surface targets, and air and naval bases in Taiwan. With the continued fielding of the PCH191, the Army is moving from simply the main ground force in a Taiwan campaign to potentially the primary contributor of tactical fires on the island. … … …

Conclusion

Within a few years of the PCH191’s initial fielding to ETC and STC artillery brigades the PLAA has moved from solely contributing landing troops to becoming one of the heaviest contributors in all phases of a future Taiwan campaign. Not only will the Army dominate the amphibious landing and subsequent ground campaign, but it also controls one of the fastest and most precise fire support weapons in the entire PLA. The PLAA’s use of the PCH191 in highly publicized exercises to intimidate Taiwan following recent politically charged visits has made it clear that China intends to use the system in a potential cross-strait campaign.

The Taiwan military has clearly become concerned by China’s well-publicized training with the PCH191 during those two events. Taiwan Ministry of National Defense (MND) press releases in 2023 reference how they are monitoring ground long-range artillery forces during and after PLA exercises.74 Regular Taiwan MND X (formerly Twitter) social media feeds also include flight paths of CH-4 UAS, demonstrating their awareness of the Army platform over the Taiwan Strait.75

Ultimately, the PLAA’s wide fielding of the PCH191 since 2019 is consistent with PLA documents calling for increased fielding of precision long-range fires to fight in future large-scale ground combat operations that have massive depths, lack contact, and require multi-domain three-dimensional operations.76 The PCH191’s mobility, accuracy, and range make the new MRL an optimal weapon for nearly all future PLA large-scale ground combat operations, not just a Taiwan fight.

***

Dr. Kirchberger applies knowledge and methodology from Sinological scholarship, policy expertise, and technical-industrial insights from three years as a naval analyst with shipbuilder TKMS!

Sarah Kirchberger, China’s Submarine Industrial Base: State-Led Innovation with Chinese Characteristics, China Maritime Report 31 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, September 2023).

About the Author

Dr. Sarah Kirchberger is Academic Director at the Institute for Security Policy at Kiel University (ISPK), a Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council, and Vice President of the German Maritime Institute (DMI). She was previously Assistant Professor of Sinology at Hamburg University and before that, a naval analyst with shipbuilder TKMS. She is the author of Assessing China’s Naval Power: Technological Innovation, Economic Constraints, and Strategic Implications (Springer, 2015), co-author of The China Plan: A Transatlantic Blueprint for Strategic Competition (Atlantic Council, 2021) and co-editor and contributor of Russia-China Relations: Emerging Alliance or Eternal Rivals? (Springer, 2022). Her research focuses on China’s undersea warfare technologies; PLAN modernization; Chinese defense-industrial development; military-technological co-operation between China, Russia, and Ukraine; EDTs in the maritime sphere; and on the strategic importance of the South China Sea. She has testified on Chinese undersea warfare before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. Kirchberger holds a Ph.D. and an M.A. in Sinology from the University of Hamburg.

The author is indebted to her colleague, Olha Husieva, for superb research assistance with Russian-language sources. Several people from the Western naval shipbuilding and military intelligence communities have kindly agreed to provide the author with some expert opinions and background assessments, but wish to remain unnamed.

Summary

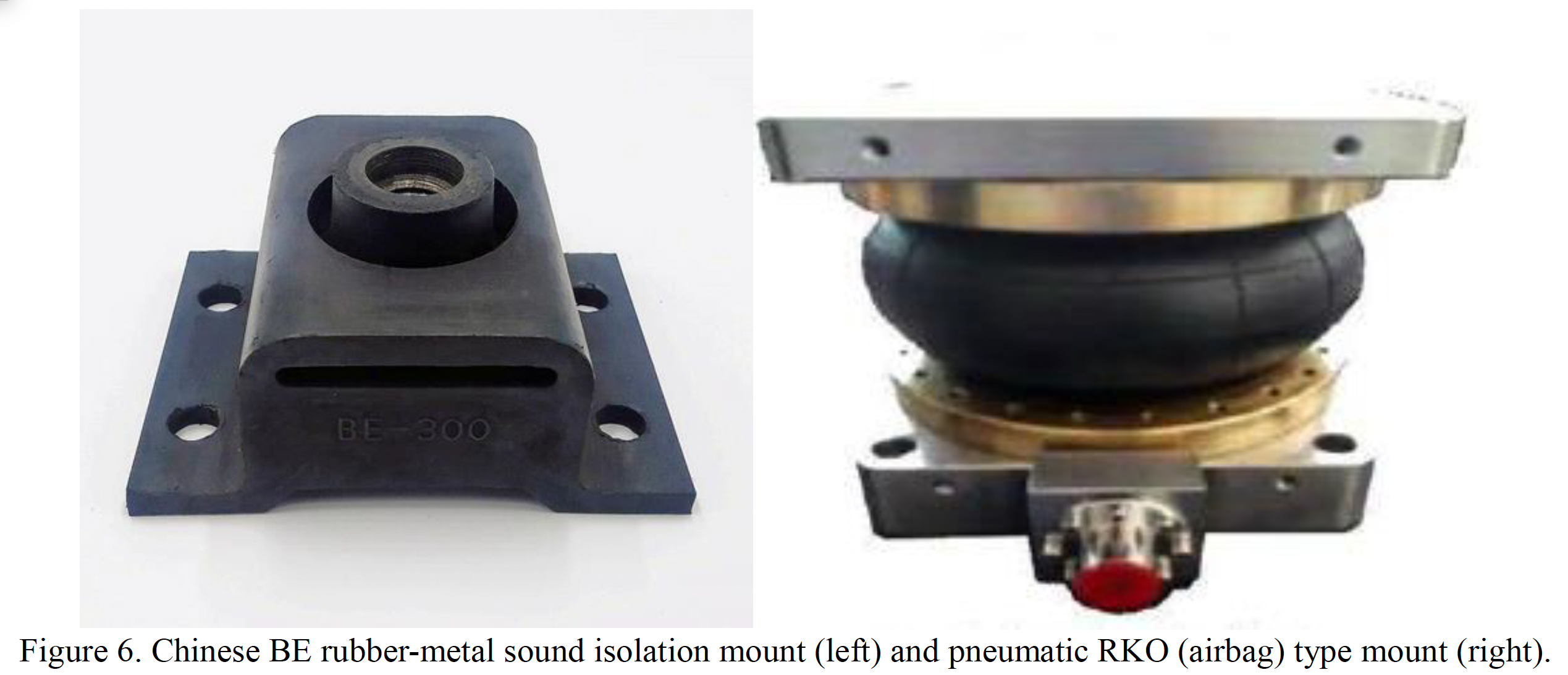

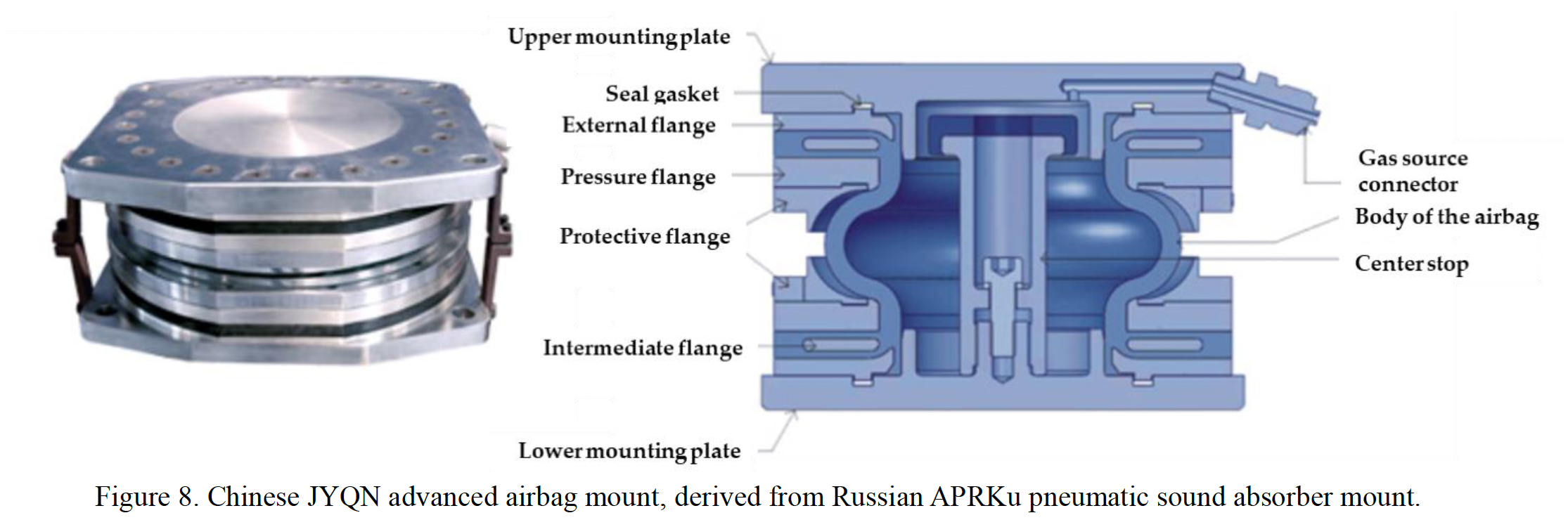

In recent years, China’s naval industries have made tremendous progress supporting the modernization of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) submarine force, both through robust commitment to research and development (R&D) and the upgrading of production infrastructure at the country’s three submarine shipyards: Bohai Shipyard, Huludao; Wuchang Shipyard, Wuhan; and Jiangnan Shipyard, Shanghai. Nevertheless, China’s submarine industrial base continues to suffer from surprising weaknesses in propulsion (from marine diesels to fuel cells) and submarine quieting. Closer ties with Russia could provide opportunities for China to overcome these enduring technological limitations by exploiting political and economic levers to gain access to Russia’s remaining undersea technology secrets.

Introduction

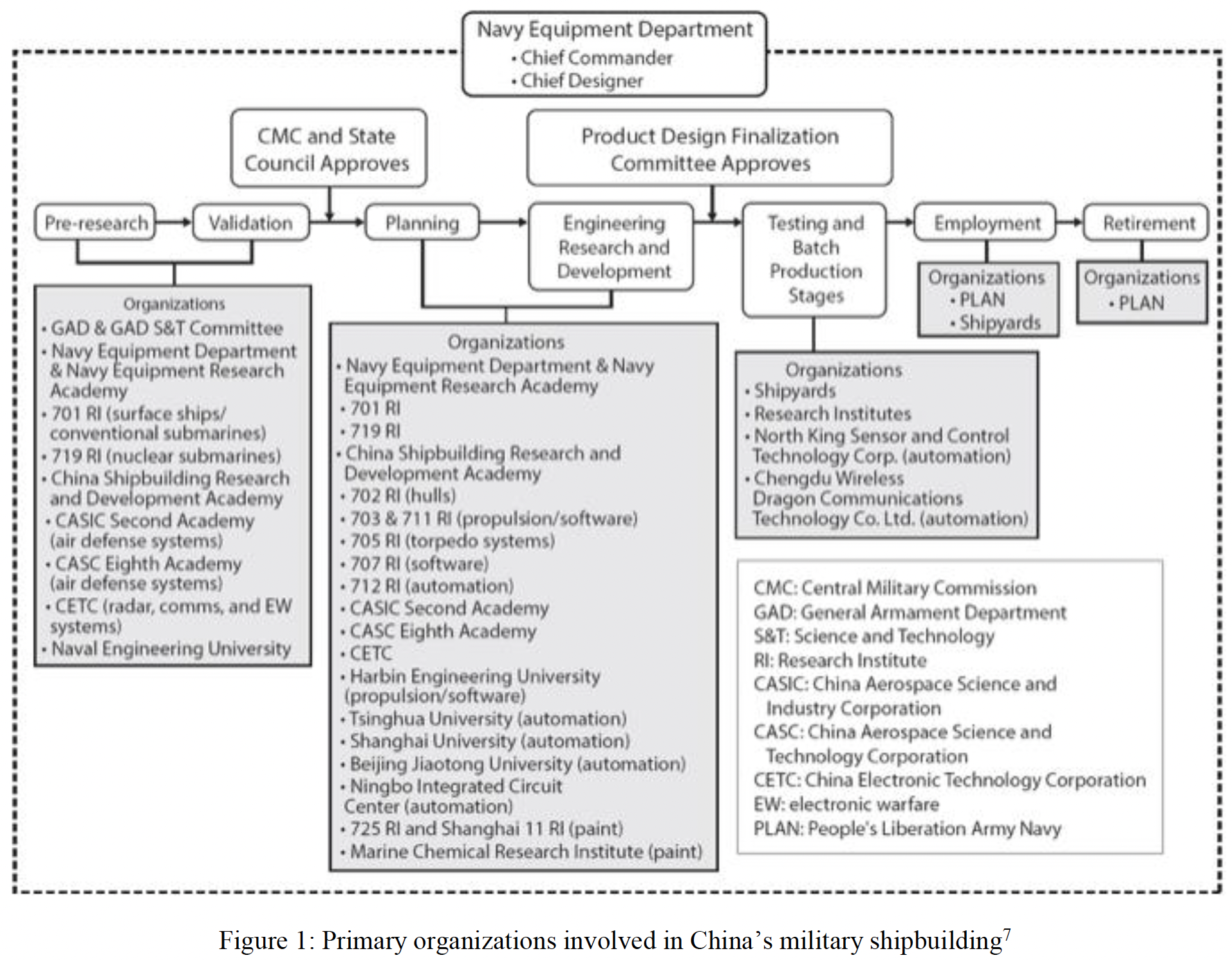

The sprawling yet opaque ecosystem of industrial and research facilities engaged in the design and production of China’s subsurface warfare systems is not easy to quantify, let alone analyze. Long hampered by the 1989 (post-Tiananmen) arms embargo, it has profited from an avalanche of state funding; is characterized by a maze of cross-shareholdings that includes state-owned banks and listed private businesses within China and abroad; connects deeply with the academic research and development (R&D) community; and is engaged in a vast effort to overcome critical arms technology bottlenecks via ingenious methods beyond traditional espionage.1 Undersea warfare technologies are of strategic priority for the Chinese government, and R&D connected to it enjoys the highest level of political backing.2

Technical details of submarine production, including of critical subsystems, are classified in all submarine-operating countries. In the People’s Republic of China (PRC), a culture of extreme secrecy in military affairs extends to even far less critical issues. Given the lack of public budgets, opaque and monopolistic procurement processes, and secret build schedules, PRC submarine procurement is shrouded in a greater degree of obscurity than that of most other countries. Sometimes, analysist discover the existence of a new submarine type only after its construction is already complete—on satellite imagery or accidentally filmed footage. This lack of transparency makes it difficult to evaluate China’s true capability at building undersea warfare systems. At the same time, China’s leaders are eager to project an image of stunning technological progress. Advances in arms production are regularly used to this end. Beijing is therefore trying to balance contradictory aims: preserving technical secrets of submarine production, while advertising breakthrough successes to signal military prowess, all the while routinely using disinformation about progress in advanced arms programs as a tool in information warfare.3

These caveats notwithstanding, there is a wealth of open sources containing hints about the arms-industrial base that is contributing to China’s submarine and anti-submarine warfare (ASW) technology programs. Even job advertisements posted on Chinese university websites targeting technical degree graduates can provide valuable detail about a particular company’s or research unit’s facilities, staffing, and business areas. Further, information from foreign subsystem suppliers to China and experiences reported by China’s submarine export customers in Thailand, Pakistan, or Bangladesh can yield interesting first-hand accounts of the actual vs. the advertised capabilities of Chinese undersea warfare systems. This report relies mostly on these and other types of openly accessible source materials supplemented with a number of background conversations with Western industry executives and submarine warfare experts.4 By combining this information with the already existing knowledge on the functioning of the Chinese arms-industrial base, and extrapolating from submarine-building experiences in other countries, this report seeks to construct at least a partial picture of the current trends, successes, and remaining technical bottlenecks characterizing China’s submarine industrial base. It also offers some cautious assessments of the operational implications for China’s future fleet development. … … …

Conclusion

Due to a combination of political will, strategic funding, and ruthless exploitation of all available means to overcome technical bottlenecks, China’s naval industries have made stunning progress in the build-up of the PLAN’s submarine force and also in the upgrading of related production facilities and R&D infrastructure. The picture of technical progress is however uneven, with somewhat surprising weaknesses remaining in certain technology areas that China could be assumed to have long mastered—mostly related to propulsion (from marine diesel engines to fuel cells) and to some quieting technologies. The performance of China’s next-generation SSNs, SSBNs, and conventional AIP submarines will show how much China’s naval industries continue to be impaired by lack of access to Western technology. Further export projects of conventional submarines such as the one in Thailand may yield more data to analyze in the future.

At the same time, China is likely already a leader in some areas of great future potential, such as AI applications in the ship design process, data exploitation for situational awareness, and potentially also in AI support for submarine commanders in their tactical decision-making.

Compared with Russia, China seems to be ahead in some areas of submarine-building—such as conventional AIP propulsion, and especially in those EDTs that require a lot of funding—but seems also still to lag behind Russia in others, in particular in quieting and nuclear propulsion. This leads to a situation of potential synergies between these two submarine-producing countries. Driven by a lack of funding, Russia’s design bureaus and industries could soon face a brain drain towards China, but the Russian state might decide to halt this trend by entering into mutually profitable synergies, e.g. related to joint production, where Russia would supply essential knowhow on submarine acoustic signature quieting, nuclear propulsion design, and hydrodynamic hull design, while China’s giant and recently modernized shipyards might supply the industrial capacity to build a lot of hulls very fast, fully exploiting economy of scale effects. A Chinese news article reported that on July 5, 2023, the Commander-in-chief of the Russian Navy, Admiral Nikolai Yevmenov, visited a naval shipyard in Shanghai. The article speculated that this might indicate Russian interest in ordering hulls from China’s yards to replenish its strained naval forces, thereby overcoming Russian shipyards’ lack of production capacity and leveraging economy of scale effects, which would be possible if an existing Chinese ship design is chosen.105

Reports of a planned joint conventional submarine design project that surfaced in mid-2020 have so far not yielded any further public information, but that does not mean it has necessarily been shelved.106 In any case, sensitive ASW and undersea warfare-related technologies including hydroacoustic sensors, underwater communication, and underwater robotics are already being jointly researched by Russian and Chinese institutes, including in the context of the “Association of Sino-Russian Technical Universities” (中俄工科大学联盟, abbreviated ASRTU) that was formed in March 2011 and is headquartered in China’s submarine hub Qingdao. At the very least, this research collaboration points to a diminishing Russian resistance to cooperation with Chinese entities both in ASW and in undersea warfare-related systems development.107

One further area of Russian-Chinese cooperation with potential repercussions for submarine-building concerns nuclear fuel deliveries. On December 12, 2022, the Russian state-owned Rosatom Corp. supplied 6,477kg of highly-enriched uranium (HEU) to China’s fast-breeder reactor CFR-600 on Changbiao Island. The weapons-grade plutonium it will soon produce could be used for warheads, but alternatively, commentators from the submarine research community have discussed the possibility that it could also be intended as fuel for future nuclear-powered submarines.108

Time will tell how far the Russian-Chinese “friendship without limits” can go in the highly sensitive area of submarine production, but it is safe to assume China would be highly interested in catching up with Russia’s remaining technological advantages, and willing to use its political and economic levers to obtain Russia’s submarine technology secrets.109

***

Christopher P. Carlson and Howard Wang, A Brief Technical History of PLAN Nuclear Submarines, China Maritime Report 30 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, August 2023).

About the Authors

Christopher Carlson is a retired Navy Reserve Captain and Department of Defense naval systems engineer. He began his navy career as a submariner but transitioned to the naval technical intelligence field in both the Navy reserves and in his civilian job with the Defense Intelligence Agency. He has co-authored several published works with Larry Bond, to include a short story and eight full-length military thriller novels. Being an avid wargamer from an early age, Carlson is one of the co-designers, along with Larry Bond, of the Admiralty Trilogy tactical naval wargames: Harpoon V, Command at Sea, Fear God & Dread Nought, and Dawn of the Battleship. He has also authored numerous articles in the Admiralty Trilogy’s bi-annual journal, The Naval SITREP, on naval technology and combat modeling.

Howard Wang is an associate political scientist at the RAND Corporation. Wang’s primary research interests include China’s elite politics, emerging capabilities in the People’s Liberation Army, and maritime security in the Indo-Pacific region. Before joining RAND, Wang served as a policy analyst for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, where he researched U.S.-China military competition and deterrence in the Taiwan Strait. He has also spent time at Guidehouse, the Jamestown Foundation, and the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Wang completed his Doctorate in International Affairs (DIA) at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, where he was awarded distinction for his thesis research on the Chinese Communist Party’s sea power strategy. He completed his Master’s in Public Policy at the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy and his bachelor’s degree at Boston University.

Summary

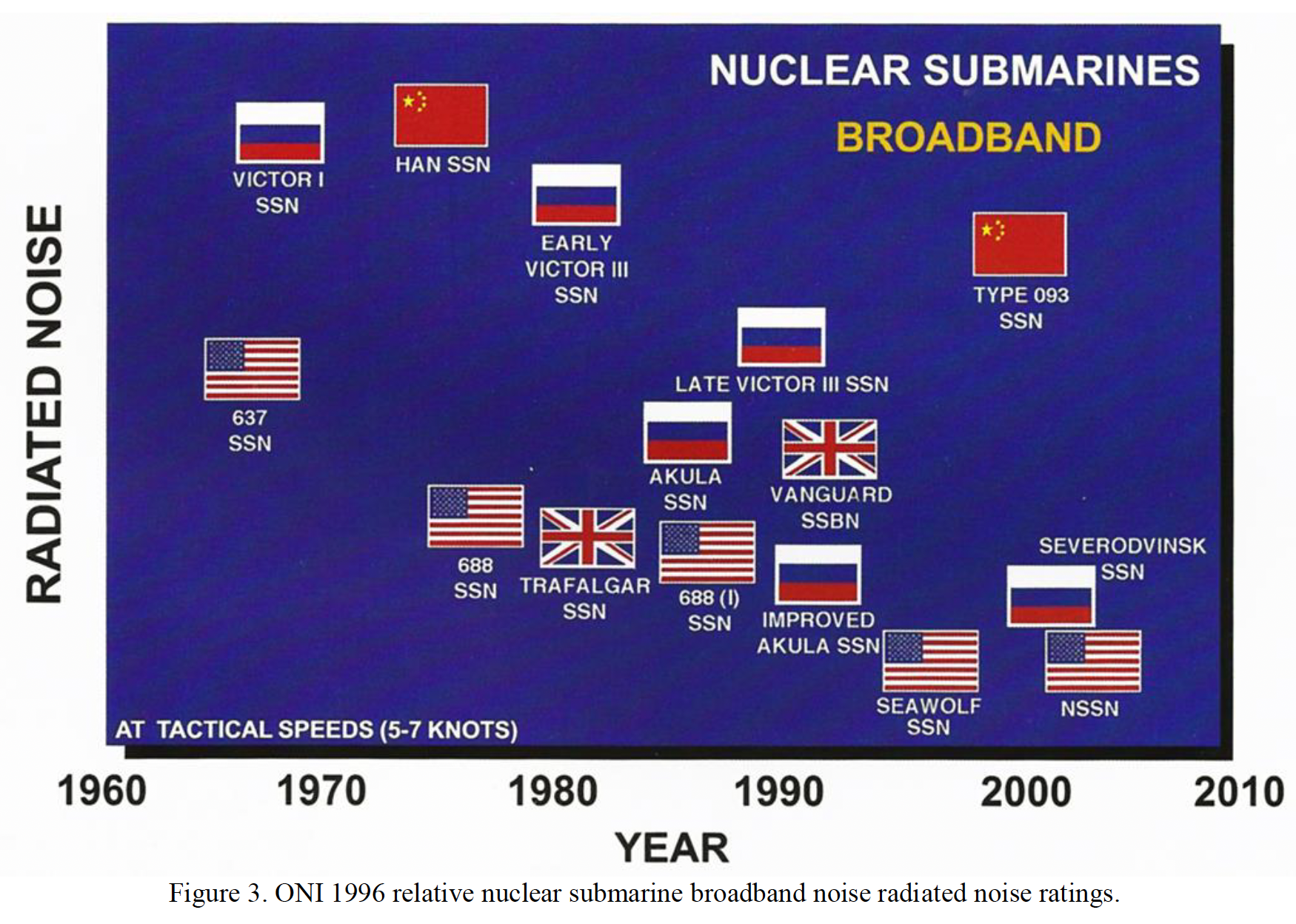

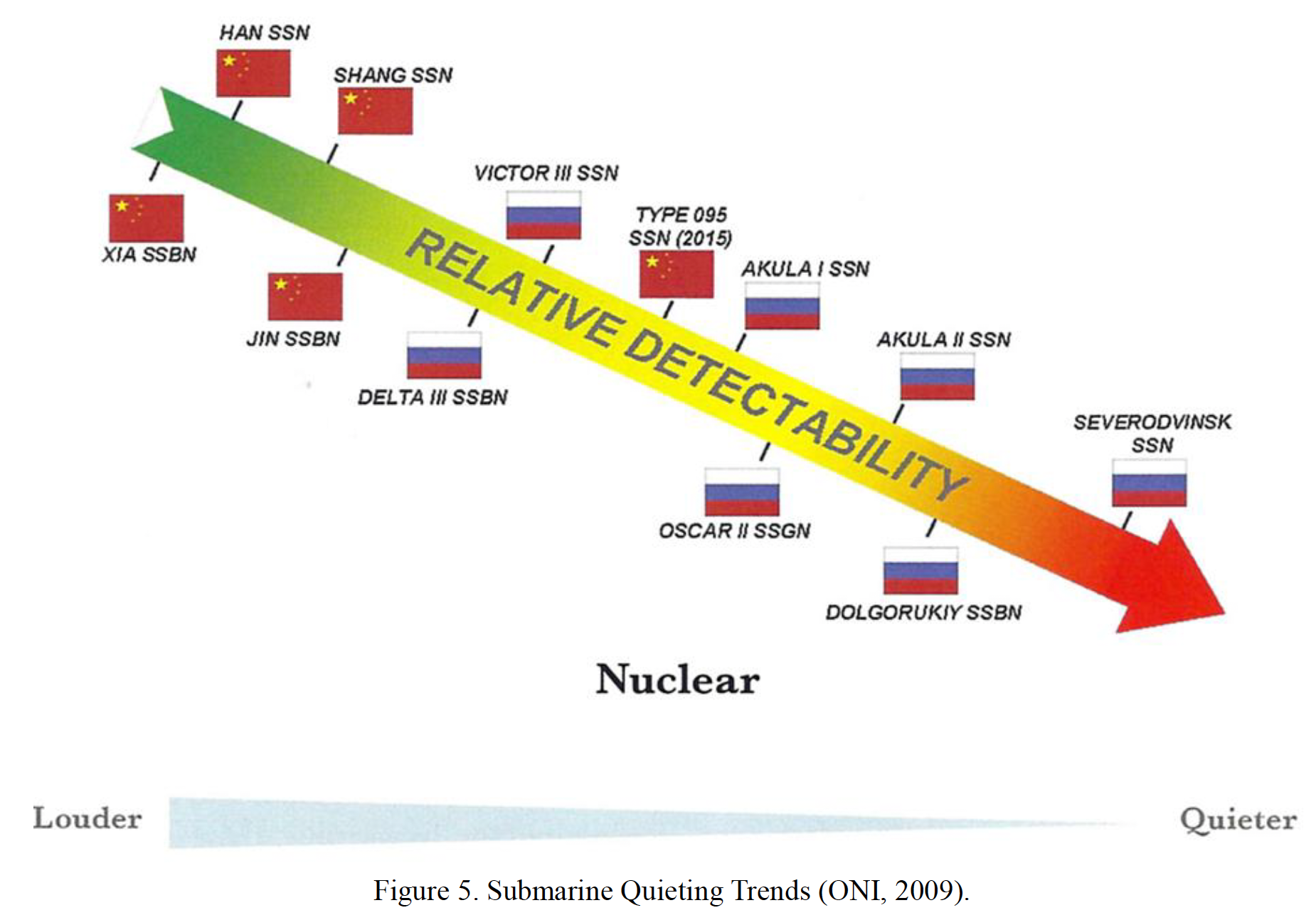

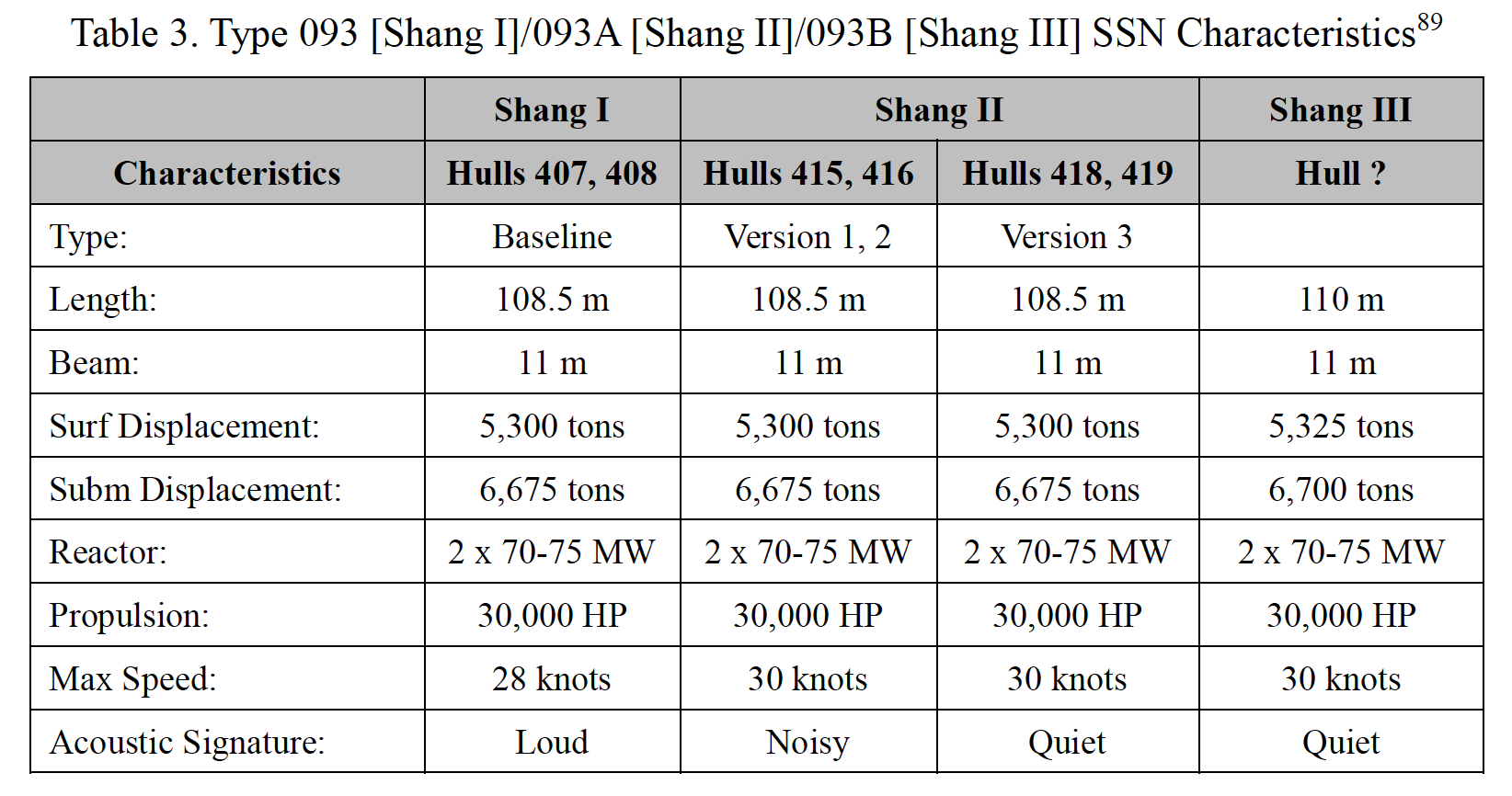

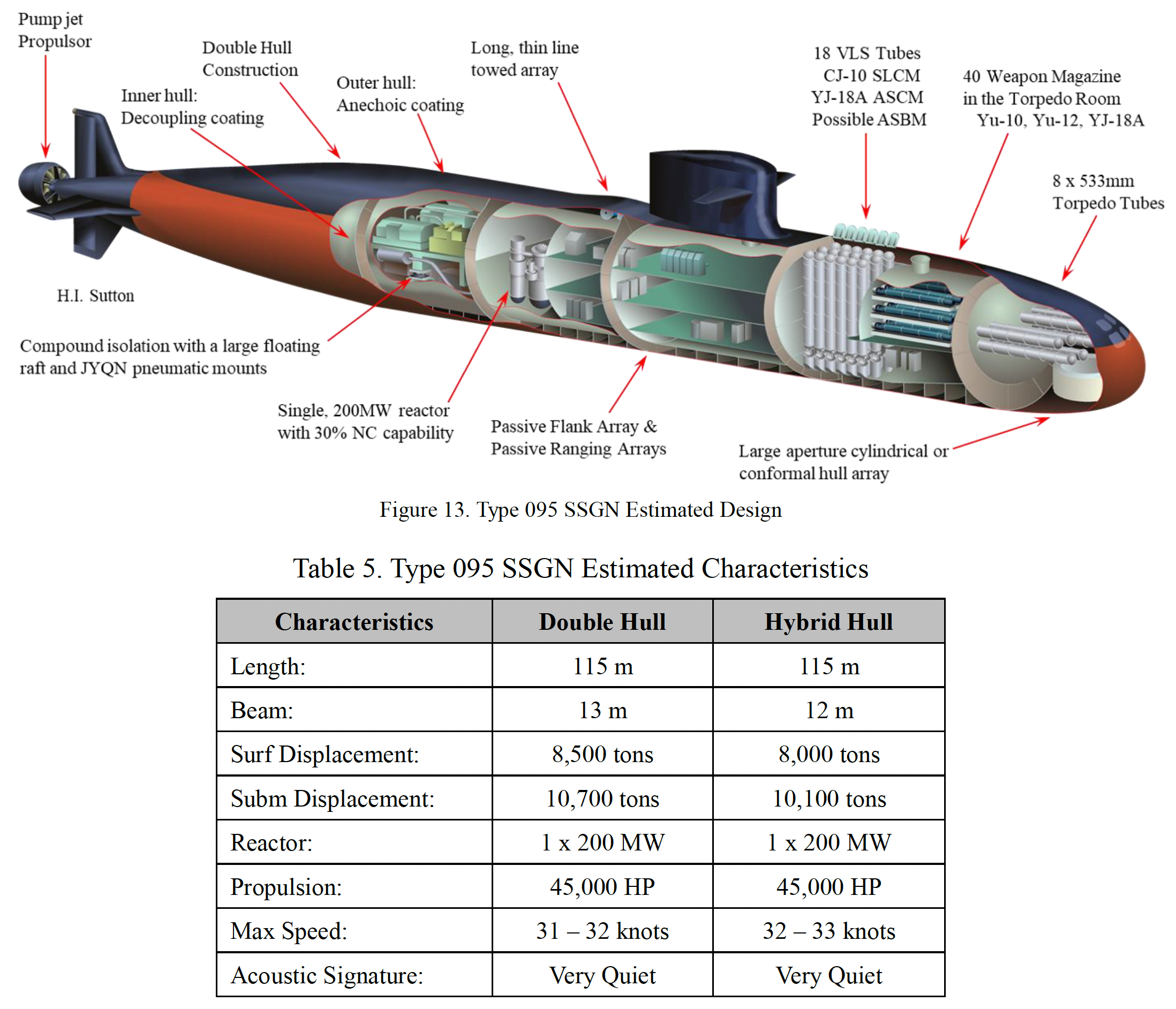

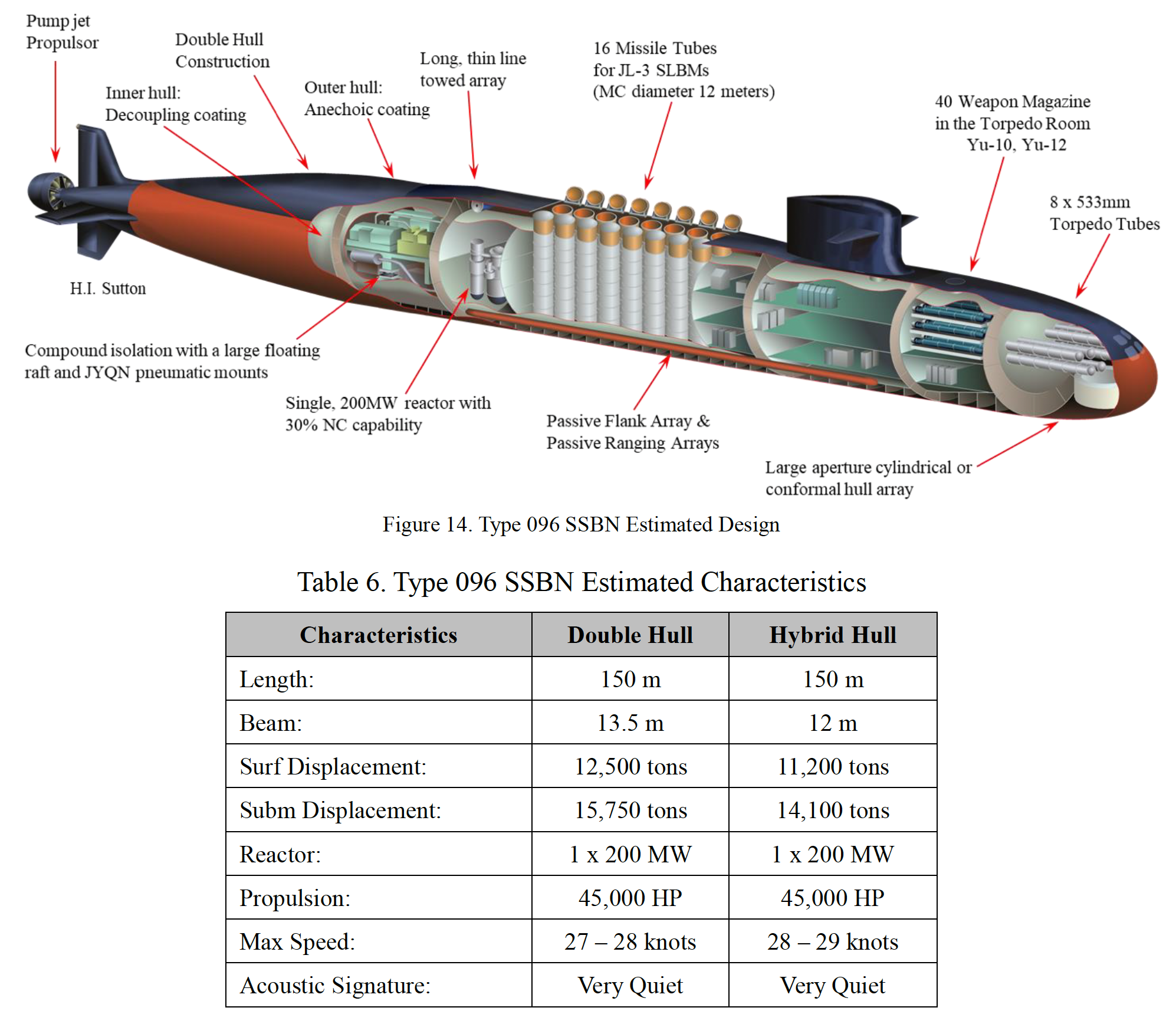

After nearly 50 years since the first Type 091 SSN was commissioned, China is finally on the verge of producing world-class nuclear-powered submarines. This report argues that the propulsion, quieting, sensors, and weapons capabilities of the Type 095 SSGN could approach Russia’s Improved Akula I class SSN. The Type 095 will likely be equipped with a pump jet propulsor, a freefloating horizontal raft, a hybrid propulsion system, and 12-18 vertical launch system tubes able to accommodate anti-ship and land-attack cruise missiles. China’s newest SSBN, the Type 096, will likewise see significant improvements over its predecessor, with the potential to compare favorably to Russia’s Dolgorukiy class SSBN in the areas of propulsion, sensors, and weapons, but more like the Improved Akula I in terms of quieting. If this analysis is correct, the introduction of the Type 095 and Type 096 would have profound implications for U.S. undersea security.

Introduction

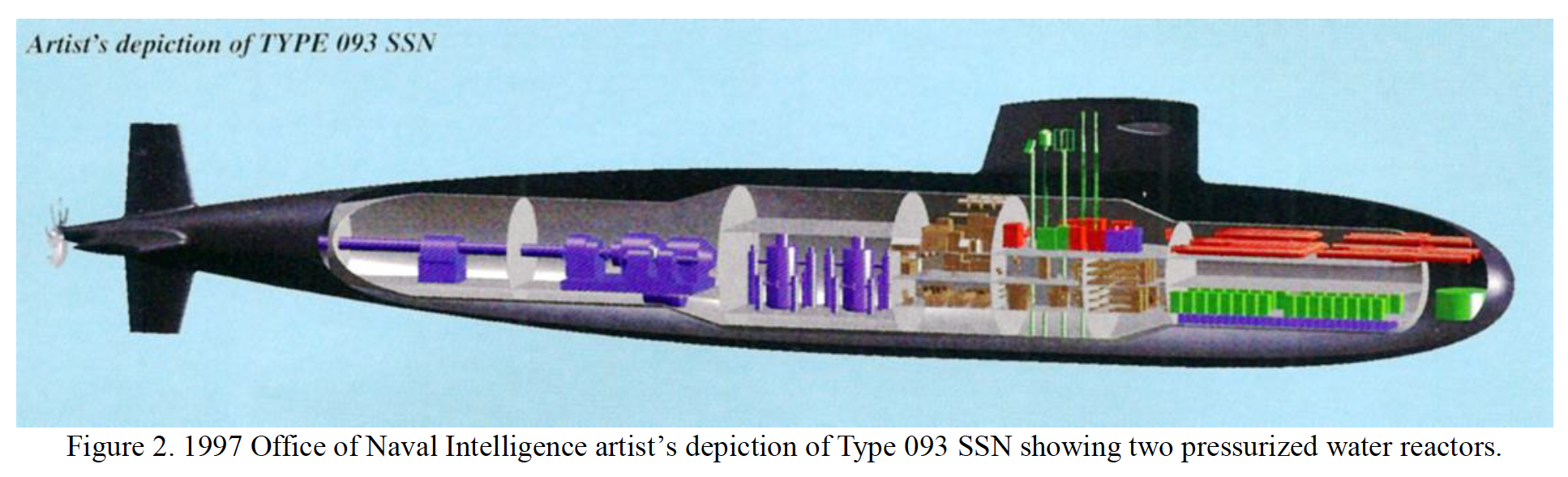

It has been some 55 years since the People’s Republic of China (PRC) began building its first nuclear-powered submarine, and the journey has been anything but smooth sailing. China began its nuclear submarine program in July 1958 when Mao Zedong and the Central Military Commission (CMC) authorized the “09 Project.” Mao seemed to appreciate the enormity of the challenge, as China possessed neither the intellectual or industrial capability necessary, and he was persistent in asking the Soviet Union for assistance. Finally, in October 1959, after being rebuffed numerous times, Mao issued the decree that China would proceed on a path of self-reliance in the development of nuclear submarines.1

For the next five years, progress was slow, caused by the severe lack of nuclear expertise and the political and economic chaos from Mao’s Great Leap Forward. The submarine program was also competing for the same talent and funding needed for the development of atomic weaponry, and it soon became apparent that the two projects could not be pursued simultaneously. Thus, in March 1963 the submarine program was postponed and only a small cadre of engineers continued doing technical exploration on nuclear propulsion.2 In other words, it was a research project tasked with gathering every scrap of information on how other countries used nuclear propulsion in ships and submarines. After China successfully detonated its first atomic bomb on 16 October 1964, the CMC revisited the nuclear submarine program and authorized its restart in March 1965.3 The research project ended, and the submarine design process began in earnest. … … …

Conclusion

The PLAN has had a rough road to travel in achieving its goal of producing nuclear-powered submarines. After being denied technical support by the Soviet Union numerous times, China proceeded on the path of self-reliance to design and build nuclear submarines with indigenous capabilities only. The result was that China built functional, but not very effective submarines.

In an ironic historical twist, China was able to obtain submarines, technologies, and design assistance from cash-strapped Russia starting in the mid-1990s. Through the process of “imitative innovation” Chinese engineers learned how to duplicate and then improve the technologies they had purchased. But this process took time, and the existing Type 093 and 094 submarine hulls were just too small to take full advantage of the technology that had been developed. After nearly 50 years since the first Type 091 SSN was commissioned, China is finally on the verge of producing world-class nuclear-powered submarines.

If the analyses presented above prove to be accurate, then the Type 095 has the potential to approach the propulsion, quieting, sensors, and weapons capabilities of Russia’s Improved Akula I class SSN. The Type 096 will also see significant improvements over its predecessors and could compare favorably to Russia’s Dolgorukiy class SSBN in the areas of propulsion, sensors, and weapons, but more like the Improved Akula I in terms of quieting. Should China successfully make the jump in capabilities from the current Victor III-like platform (Type 093A Version 3) to an Improved Akula I-like platform, the implications for the U.S. and its Indo-Pacific allies would be profound.

***

Brian Waidelich and George Pollitt, PLAN Mine Countermeasures, Platforms, Training, and Civil-Military Integration, China Maritime Report 29 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, July 2023).

Unique insights on the latest PRC military maritime capabilities and trends from two brilliant, cutting-edge researchers, based on one of the very best papers delivered at CMSI’s April 2023 “Chinese Undersea Warfare” conference!

About the Authors

Brian Waidelich is a Research Scientist at CNA’s Indo-Pacific Security Affairs program. His research focuses on PLA organization and Indo-Pacific maritime and space security issues. Brian received a Master of Arts in Asian studies from Georgetown University and Bachelors of Arts in Chinese and English from George Mason University. He has also studied at the Nanjing University of Science and Technology.

A former Air Force navigator, George Pollitt began work in mine countermeasures (MCM) in 1971 as Technical Agent for the Mine Neutralization Vehicle System at the Naval Ship Engineering Center. He programmed MCM tactical decision aids for OPERATION END SWEEP, the clearing of mines in Haiphong, and developed MCM tactics in Panama City, FL before transferring to the Commander Mine Warfare (COMINEWARCOM) Staff, where he worked as an MCM analyst, Advisor for Research and Analysis, and Technical Director. He participated in OPERATION EARNEST WILL, the Tanker War, testing systems in the Persian Gulf to enable warships to detect mines, and he analyzed the DESERT STORM Clean-Up Operation on scene for Commander Middle Eastern Forces. At the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, he led studies on MCM platforms and systems and the Maritime 9-11 Study. Most recently he evaluated the MK 18 Mine hunting UUV system as the Independent Test and Evaluation Agent. George has an ME in Aerospace Engineering from the University of Florida and a BS in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Central Florida.

Summary

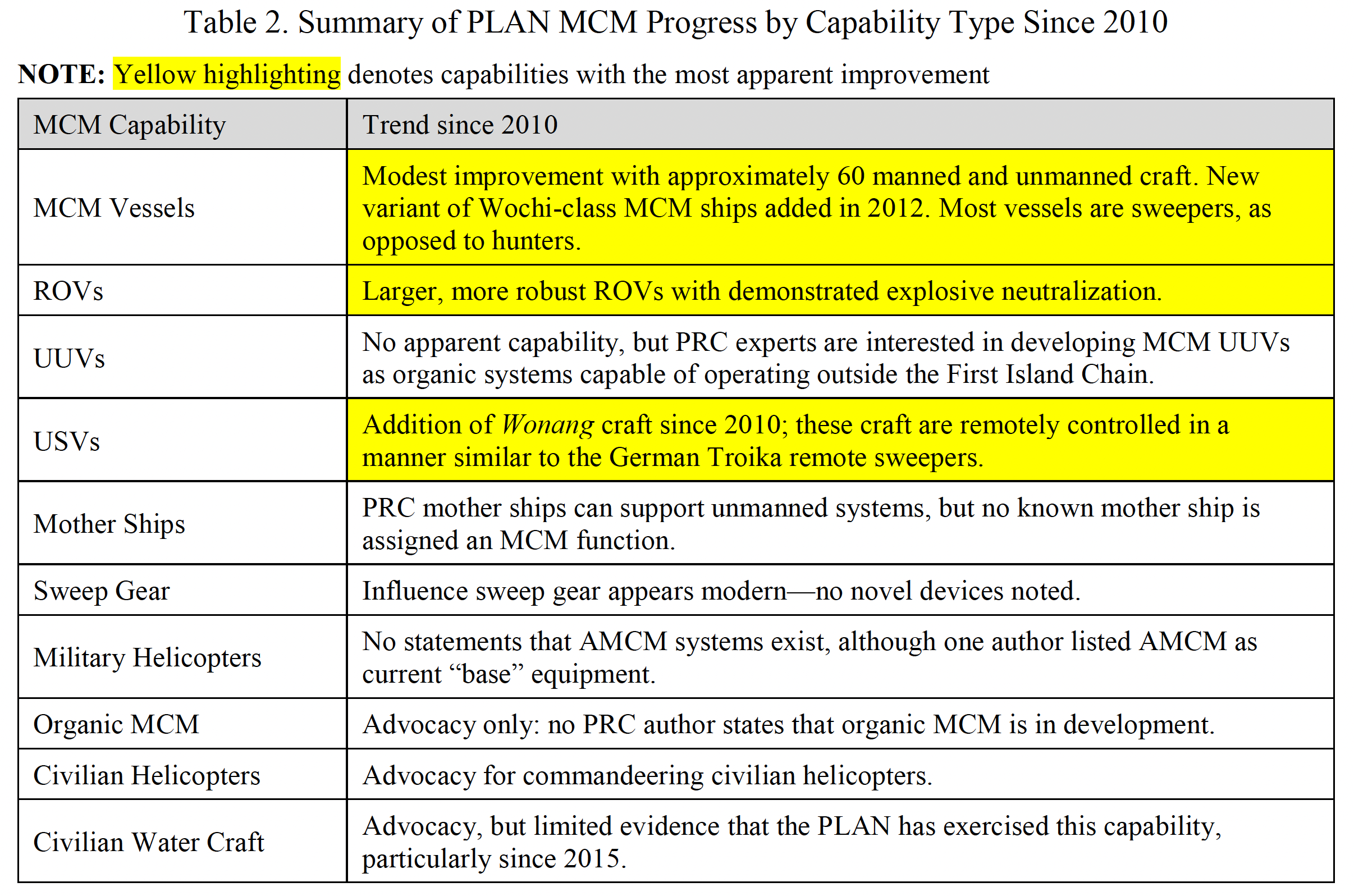

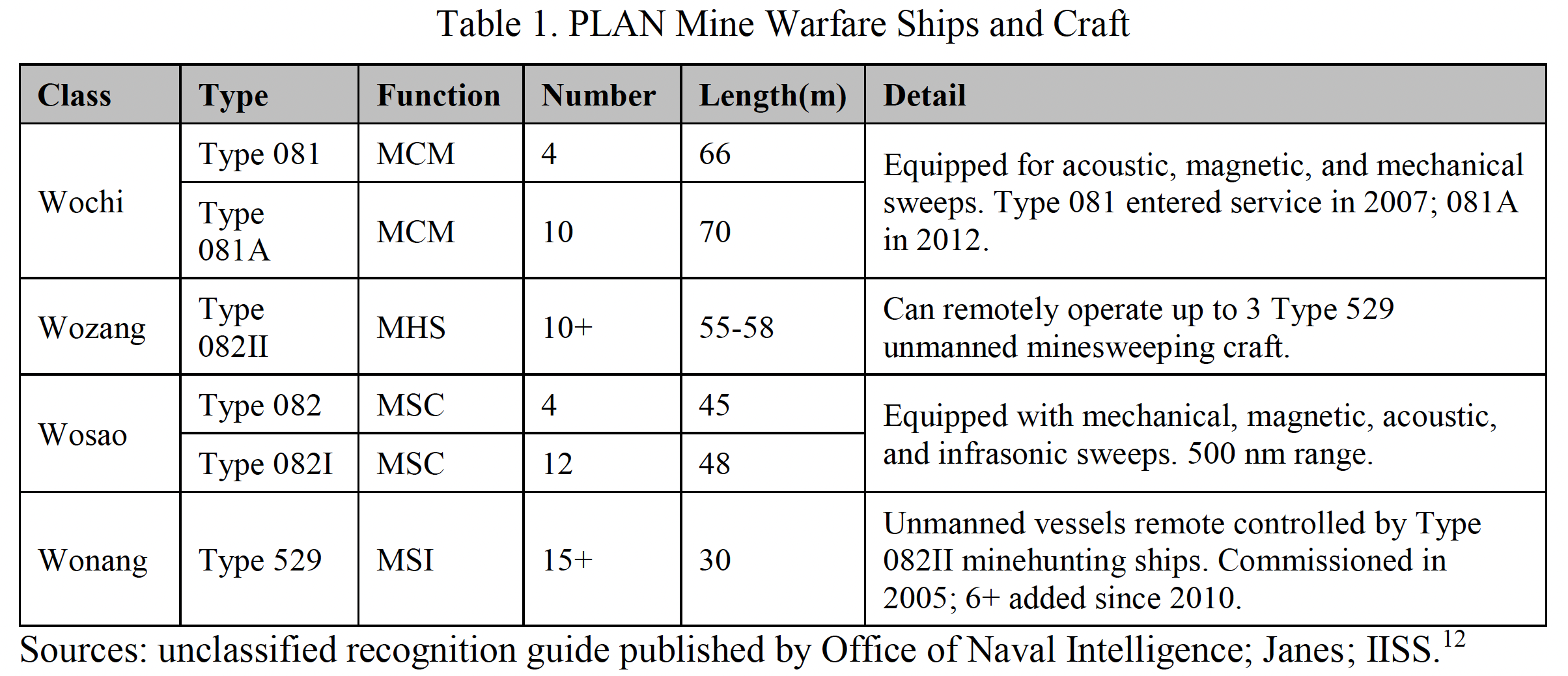

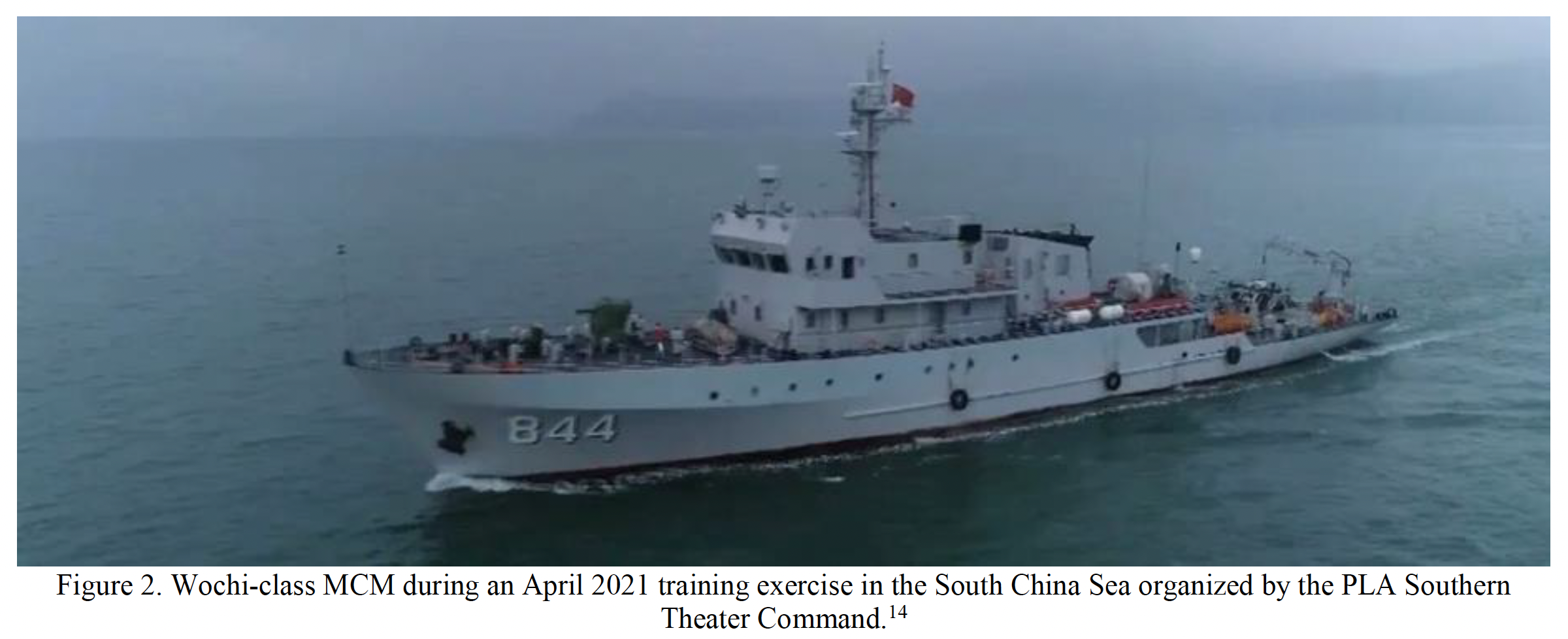

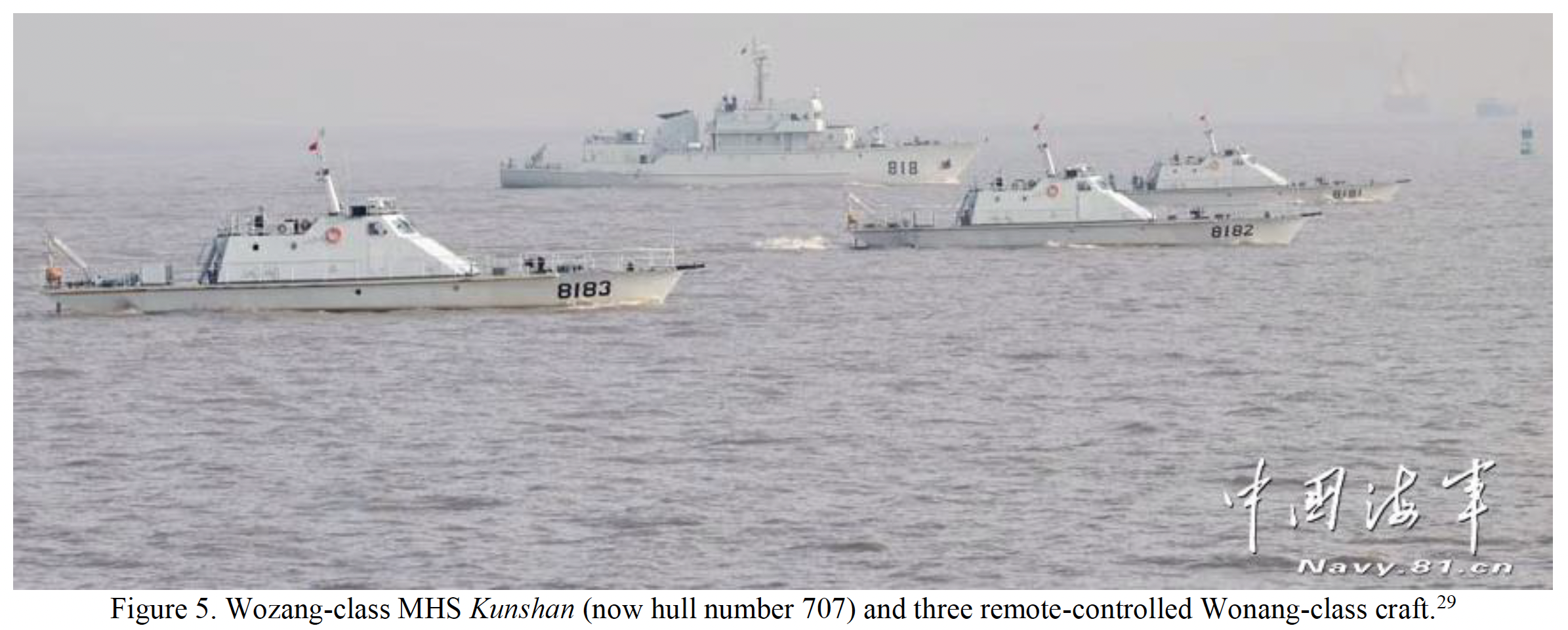

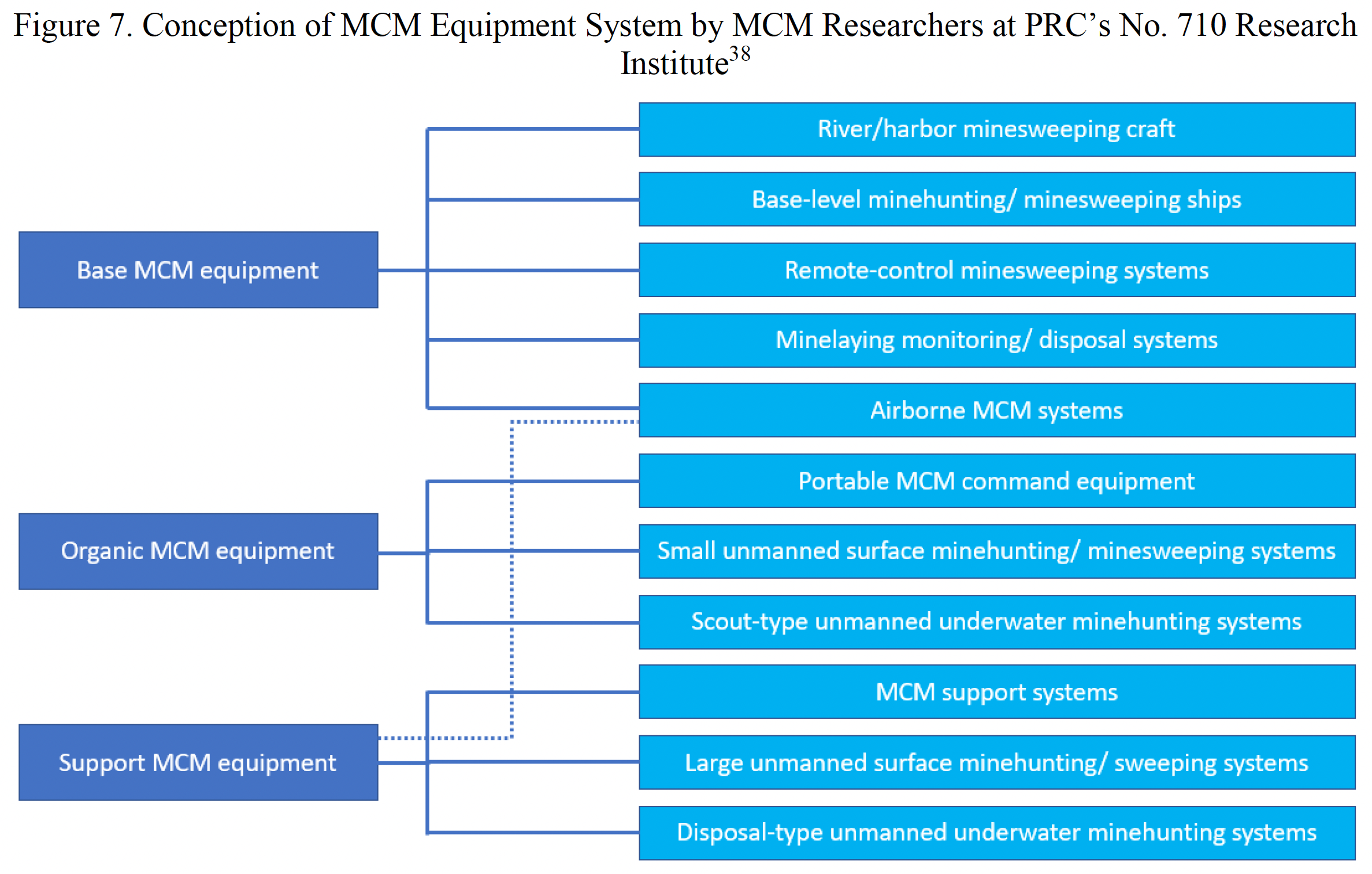

The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has made incremental progress in its mine countermeasures (MCM) program in recent years. The PLAN’s current inventory of about 60 MCM ships and craft includes classes of minehunters and minesweepers mostly commissioned in the past decade as well as unmanned surface vessels (USVs) and remotely operated vehicles with demonstrated explosive neutralization capability. Despite the addition of these advanced MCM platforms and equipment, experts affiliated with the PLAN and China’s mine warfare development laboratory have serious reservations about the PLAN’s current ability to respond to the full range of likely threats posed by naval mines in future contingencies. The PLAN’s MCM forces are currently organized for operations near China’s coastline, but writings by Chinese military and civilian experts contend that to safeguard Beijing’s expanding overseas interests, the PLAN must develop MCM capabilities for operations far beyond the First Island Chain. PLAN and civilian mine warfare experts have proposed various solutions for offsetting perceived shortcomings in the PLAN’s MCM program, including the development of autonomous USVs and unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), deployment of modularized MCM mission packages on ships such as destroyers and frigates, and mobilization of civilian assets such as ships and helicopters in support of MCM operations. Although there appears to have been little to no adoption of these proposed solutions to date, the PLAN recognizes MCM as one of its biggest challenges, and one can expect the PLAN to continue making measured progress in its MCM program in the years ahead.

Introduction

This report provides an overview of Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) mine countermeasures (MCM) capabilities, with a focus on related naval platforms and equipment, civil-military integration, and training activities. This report updates previous Western research on PLAN MCM, with an eye toward developments since 2010.1

The detection and neutralization of adversary naval mines is an important capability for all maritime powers, and China is no exception. Minefields deprive enemy ships of freedom of maneuver and eliminate their mobility. The laying of mines, or even the suspicion that mines have been laid in a strategic waterway such as a harbor or strait, can be enough to deter a country lacking in MCM capability from transiting that waterway. It is more difficult to clear mines than to lay mines, and mines are significantly cheaper per unit than the enemy combatants they threaten to cripple or destroy. To retain freedom of maneuver, it is imperative for maritime powers to develop MCM capability to ensure the safe passage of their commercial shipping and naval forces, especially during crisis and conflict.

In this report, we argue that the PLAN recognizes the importance of modernizing and expanding its MCM capability to operate in both “near seas” and “far seas” environments, but that evidence to date shows they have made limited progress toward this goal, possibly due to competition for resources with other naval warfare communities. We find that most or all of the PLAN’s current inventory of about 60 dedicated mine warfare ships and craft, as well as MCM equipment including remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), is likely intended for operations within the First Island Chain. We also note People’s Republic of China (PRC) interest in using civilian platforms to augment its MCM capability, although there is little evidence of recent training or investments in this area. We found that the PLAN currently maintains an inventory of remotely-controlled mine sweeping USVs but appears to lack minehunting UUVs, despite the fact that PRC shipbuilders are clearly capable of building related platforms.

The data analyzed for this report was drawn primarily from Chinese-language technical journal and newspaper articles published between 2010 and 2022. Priority was given to articles authored by individuals with credible ties to China’s MCM program, namely authors with institutional affiliations to the PLAN and to the state-owned China State Shipbuilding Corporation’s (CSSC) No. 710 Research Institute, China’s mine warfare development laboratory.2 As with any analysis of PLA capabilities based on publicly available writings, this report presents a partial and likely incomplete picture of the initiatives underway in China’s MCM development, some of which may be classified or otherwise deemed too sensitive for public disclosure.

The remainder of this report is organized as follows. Section one examines PRC military and civilian authors’ views of the naval mine threat environment and motivations for expanding the PLAN’s MCM capability outside the First Island Chain. The second section lays out what is currently known from publicly available sources on the PLAN’s current MCM capability (platforms, equipment, etc.) as well as capabilities it may be developing based on evidence from PRC writings. In the third section, we discuss PRC views on incorporating civilian platforms such as ships, helicopters, and UUVs into MCM operations and the types of tasks those civilian platforms could potentially undertake. The fourth section offers a brief overview of MCM training exercises carried out within the PLAN and with foreign militaries. The final section summarizes observed progress in the PLAN’s MCM capability since 2010 and compares the differing approaches to MCM in the PLAN and U.S. Navy. … … …

Conclusion

The PLAN’s General View of MCM

PRC military and civilian authors offer rather bleak assessments of the PLAN’s existing capability to neutralize enemy mine threats, particularly as the PLAN operates at greater distances from mainland China. As Hu Ce, an author from the No. 710 Research Institute put it, a naval blockade could stress the PLAN’s existing MCM capability to the point that “the survivability and operations of the Chinese Navy’s forces would be seriously challenged” and that “the national economy and even the strategic overall situation could be affected” (emphasis added).67 A senior engineer from the PLAN’s Yichang Area Military Representative Office, emphasized the near seas-centric role of existing PLAN MCM forces, stressing that they are “seriously inadequate [for] supporting mid- and far seas protection operations.”68

Despite PRC authors’ self-acknowledged shortcomings, a comparison with past Western analyses of PLAN MCM capability demonstrates that the PLAN has in some respects made progress in fielding more advanced MCM platforms and equipment. PRC military and civilian subject matter experts have also advocated for advancements in a variety of unmanned MCM capabilities and the integration of civilian assets, although little or no evidence of progress in these areas has been observed in publicly available sources. We summarize related developments since 2010 in Table 2 below.

Autonomous Platforms

There is much advocacy in PRC writings for the integration of military or civilian autonomous platforms, including USVs and UUVs, for MCM operations. Apart from the PLAN’s existing Wonang-class remotely-controlled craft, however, we saw no evidence of the PLAN fielding such platforms for MCM purposes or bringing analogous civilian platforms in for demonstrations or training exercises.

Conventional Minehunting

The press has noted that Chinese MCM ships are not modern ships made from fiberglass, as are Western MCM ships, and that emphasis has been placed on mine sweeping over mine hunting. With China’s technical skill in automation and with the emphasis in PRC writings on increasing the use of unmanned platforms throughout the force, it seems plausible that in the future the PLAN may skip further development of conventional minehunting and go directly to highly automated unmanned minehunting.

Range of Operations

What is publicly known about the capabilities and ranges of PLAN MCM ships and craft, coupled with accounts of their shortcomings by PRC authors, suggests that current MCM craft must operate relatively close to mainland bases. They may lack the ability to achieve full coverage of waters within the First Island Chain.

Organic MCM

One PRC author claims it is especially important for the PLAN to have “organic MCM” capabilities for “far-seas missions,” i.e., for PLAN missions outside the First Island Chain in which dedicated MCM platforms are less likely to be available. As they pointed out, during far-seas operations, specialized MCM forces are usually unavailable, so forces must “save themselves” by relying on their own capabilities to counter naval mines.69 However, it has not been explicitly stated in the literature that the PLAN has been developing systems for organic MCM for ships in the far seas. PRC media reviewed for this report did show examples of PLAN destroyers or frigates conducting MCM training, but this was limited to relatively simple fires against floating mines.

Use of Civilian Assets

PRC writings portray MCM support missions as a natural avenue of civil-military cooperation that builds upon decades of past practice. However, the writings did not reference recent examples of the actual use or training in the use of non-PLAN platforms. A logical civil-military cooperation for MCM would be to use fishing craft to perform MCM functions, as the British did in World War I. Civilian ships are available that could tend multiple unmanned systems as mother ships, but PRC civilian and military authors have not stated any intention of using mother ships, military or otherwise, for mine countermeasures. PLA-affiliated authors have noted that few civilian ships to date have been built to national defense standards. There are advocates within the Chinese MCM community for using civilian helicopters; but again, PRC writings have not mentioned any intention to use them.

Training

The spotty and often vague nature of PRC media reporting on PLAN training makes it difficult to generalize about PLAN MCM forces’ levels of capability and readiness. What is clear from PRC subject matter experts’ writings is that they find the state of training to be less than ideal and believe that improvements need to be made. One such area for improvement is simulation training, in which organizations throughout the PLA have been making investments in recent years.70 As one PLAN engineer argued, better MCM simulation training is necessary given the increasingly high costs and risks of conducting training with modern MCM assets and high-tech naval mines.71 Despite the advocacy, it is unclear whether PLAN leaders have the budget or inclination to build such training systems for MCM forces. Although the PLA as a whole continues to enjoy annual budget increases—7.2 percent in 2023—decision-makers are also likely facing hard budgetary choices as they commission more advanced capabilities, like aircraft carriers, and seek to use monetary incentives to improve retention and professionalism of the force.

Comparison with the U.S. Navy

Some parallels exist between the PLAN and the U.S. Navy in their attitudes toward mine warfare. In both cases, MCM is at the bottom of the priority list for assignments and careers. As a PLAN ditty begins, “if you get on a ship, don’t get on a minesweeping ship.”72 In both services, there are advocates for needed MCM capabilities, but little action is taken beyond the building of hulls.69

The main contrast between the U.S. Navy and PLAN is in the placement of their MCM assets: the U.S. Navy stations its MCM assets forward to protect the fleet, whereas the PLAN stations its assets at home to protect waters within the First Island Chain. This could change in the future as the PLA develops its existing base in Djibouti and expands its military footprint in other countries. Another difference between the two militaries is that the PLAN recognizes MCM as one of its major challenges—with some authors calling it the greatest challenge—whereas the U.S. Navy seems relatively unconcerned, especially in terms of protecting CONUS ports.

***

Michael Dahm and Alison Zhao, Bitterness Ends, Sweetness Begins: Organizational Changes to the PLAN Submarine Force Since 2015, China Maritime Report 28 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, June 2023).

About the Authors

Michael Dahm is a principal intelligence analyst at the MITRE Corporation where he focuses on Indo-Pacific security issues and challenges presented by the People’s Republic of China across the spectrum of competition. Before joining MITRE, he was a senior researcher at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory where he focused on foreign technology development. He has over 25 years of experience as a U.S. Navy intelligence officer with extensive experience in the Asia-Pacific region, including a tour as an Assistant U.S. Naval Attaché in Beijing, China, and Senior Naval Intelligence Officer for China at the Office of Naval Intelligence.

Alison Zhao is an Indo-Pacific advisor in the Commonwealth and Partner Engagement Directorate, Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security. Her prior career assignments include positions in the Defense Attaché Office, U.S. Embassy Beijing; the Joint Staff; and U.S. Forces Korea. She holds a M.A. in National Security and Strategic Studies from the U.S. Naval War College and a B.A. in International Relations and East Asian Studies from Johns Hopkins University.

The authors would like to thank the China Maritime Studies Institute’s Dr. Andrew Erickson for his encouragement to pursue this project and Ryan Martinson for his editorial review, research assistance, and constructive recommendations. The authors alone are responsible for any errors or omissions contained in this report.

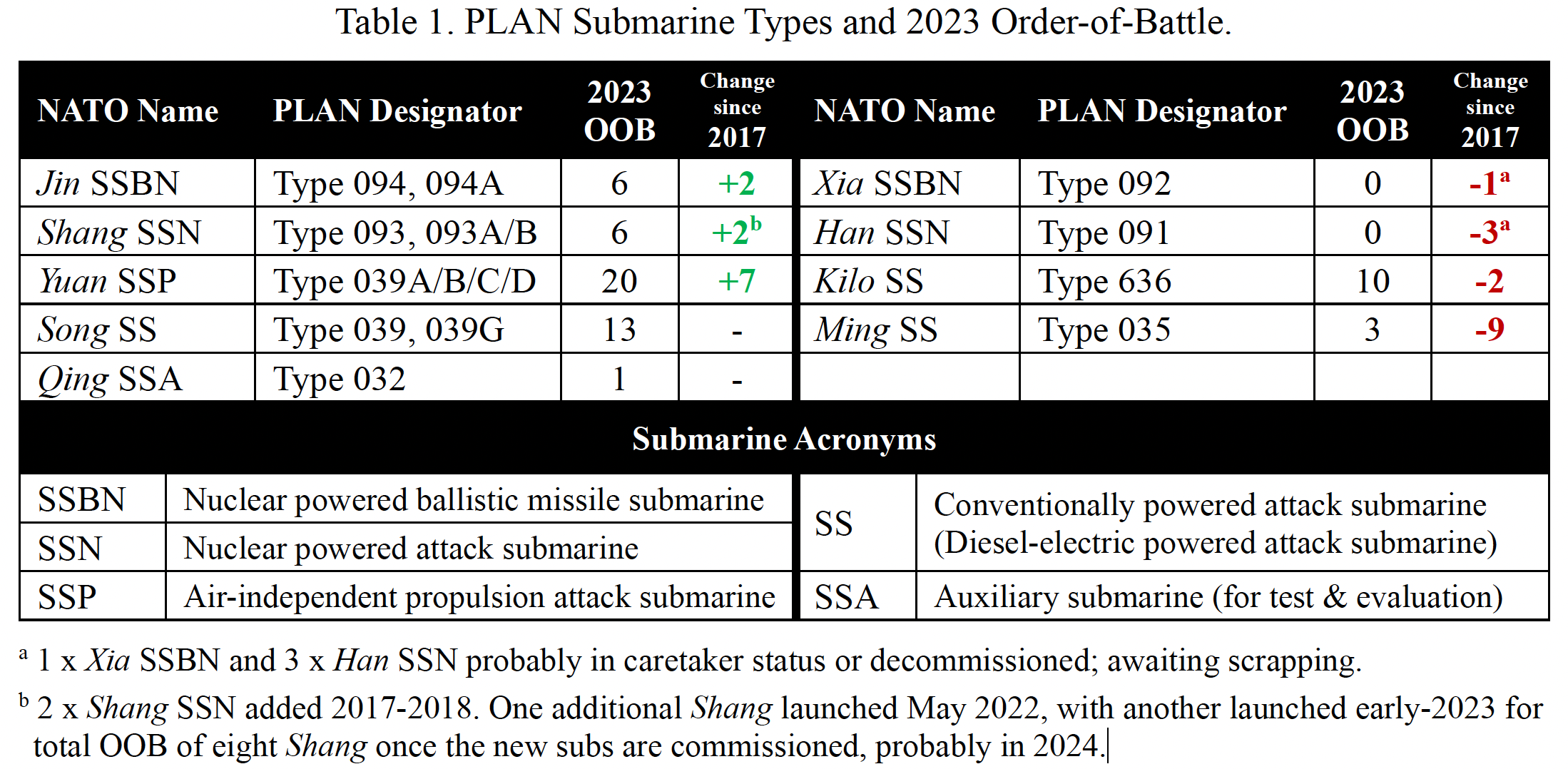

Summary

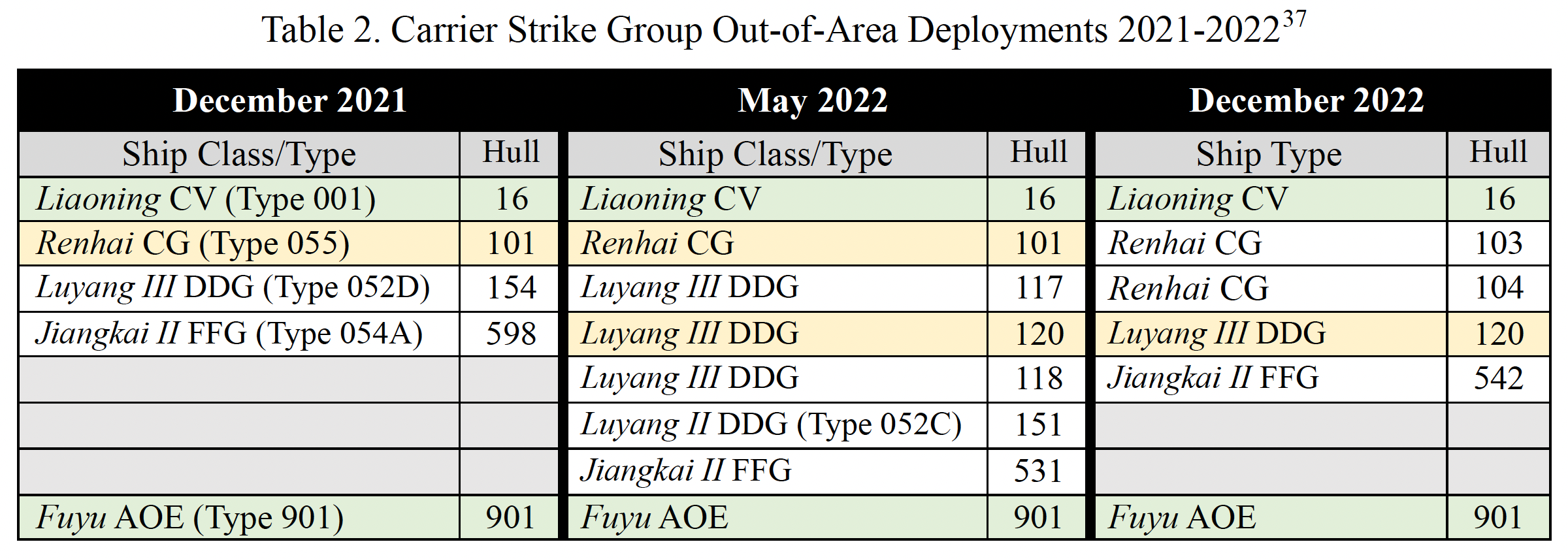

“Above-the-neck” reforms in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) that began in 2015 directed the development of a new joint operational command system that resulted in commensurate changes to PLA Navy submarine force command and control. Additional changes to tactical submarine command and control were driven by the evolution and expansion of PLA Navy surface and airborne capabilities and the introduction of new longer-range submarine weapons. Follow-on “below-theneck” reforms inspired significant organizational change across most of China’s military services. However, the PLA Navy submarine force, for its part, did not reorganize its command structure but instead focused on significant improvements to the composition and quality of its force. Between 2017 and 2023, the PLA Navy submarine force engaged in a notable transformation, shuffling personnel and crews among twenty-six submarines—eleven newly commissioned and fifteen since retired—relocating in-service submarines to ensure an equitable distribution of newer, more capable submarines across the fleet. Observations of infrastructure improvements at PLA Navy submarine bases portend even more changes to submarine force structure in the coming years.

Introduction

Since the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) reforms began in 2015, the PLA Navy (PLAN) submarine force has likely endured one of the most tumultuous transformations in its history. “Bitterness ends, sweetness begins” (苦尽甘来) is a Chinese idiom that means the worst is over and better times lie ahead. While the reforms were probably difficult to swallow for the submarine force, they have almost certainly had a positive impact on PLAN undersea warfare capabilities.

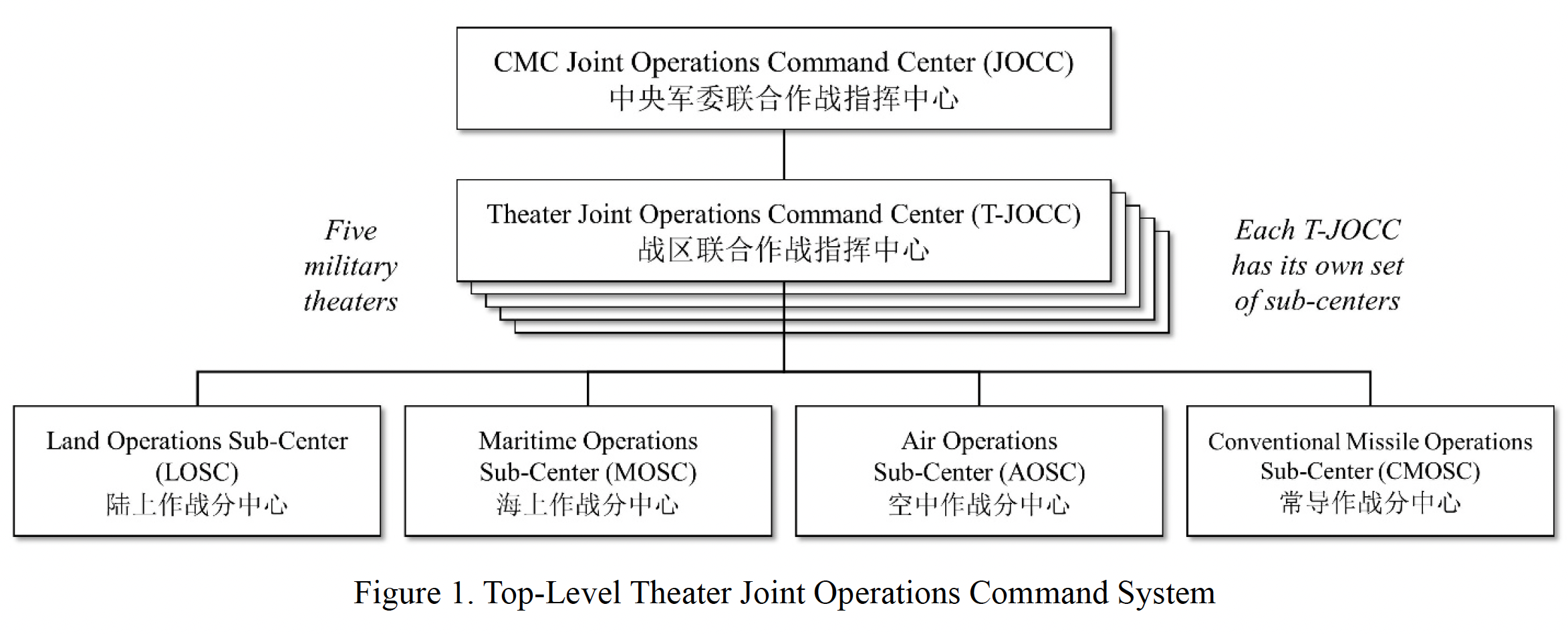

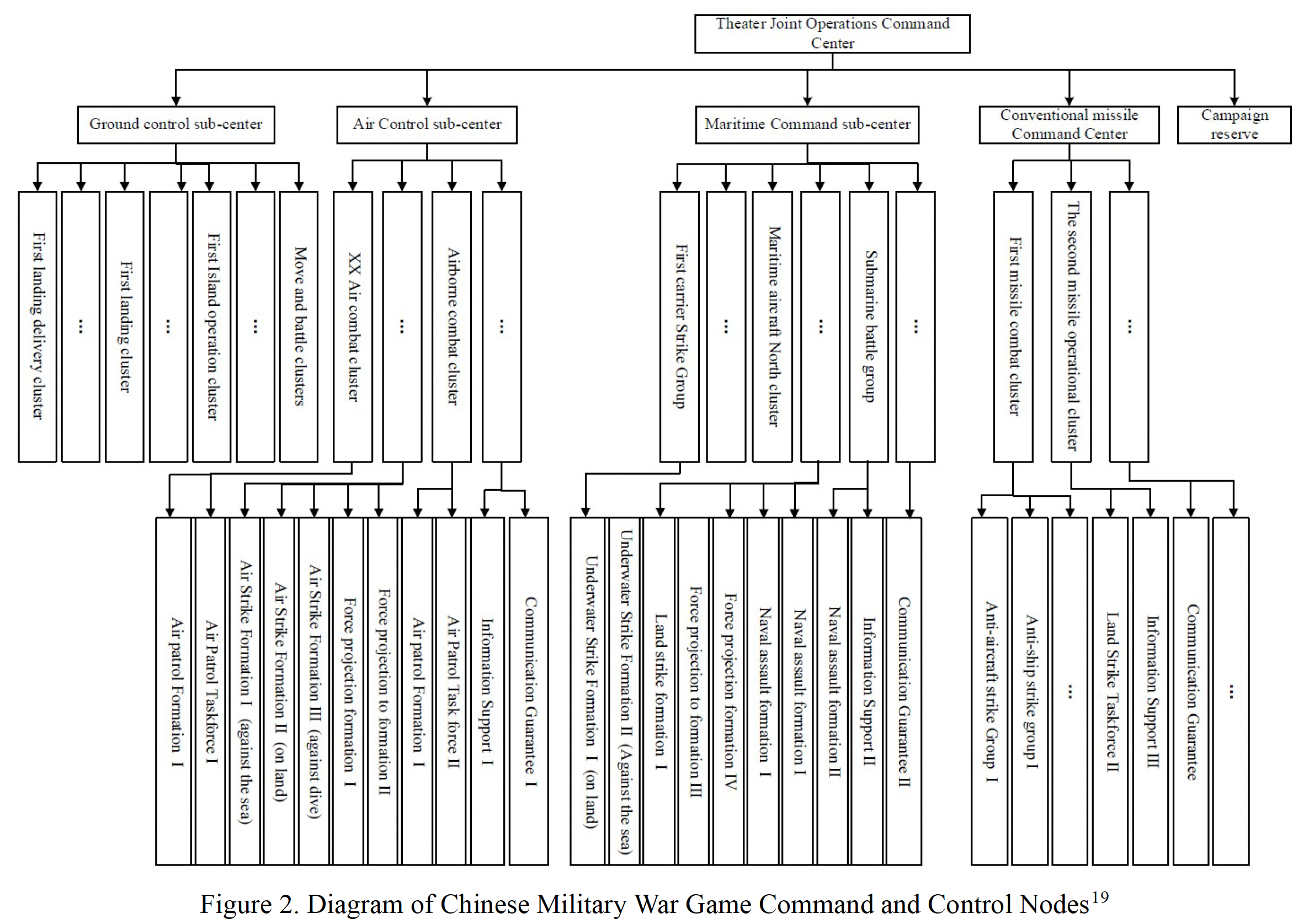

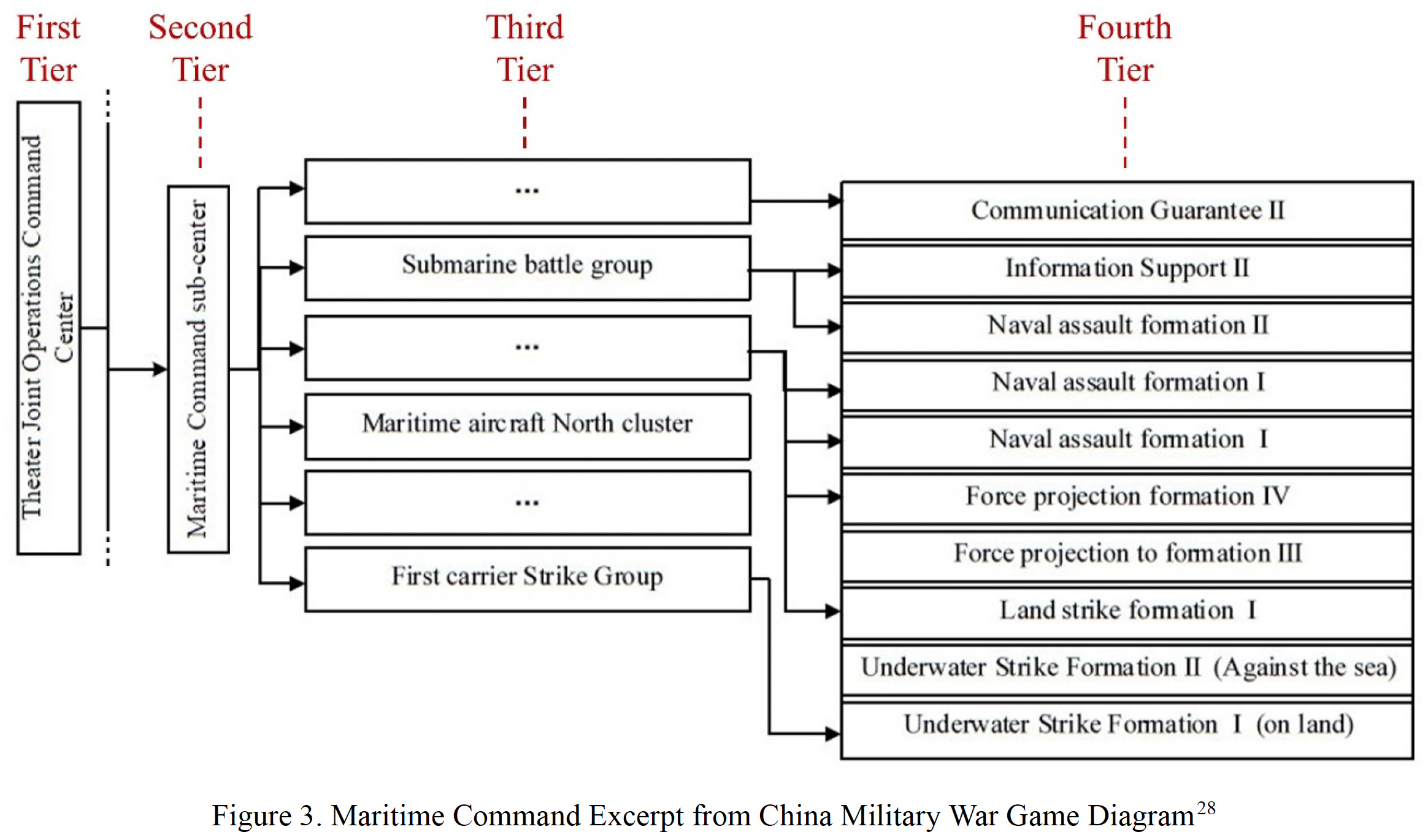

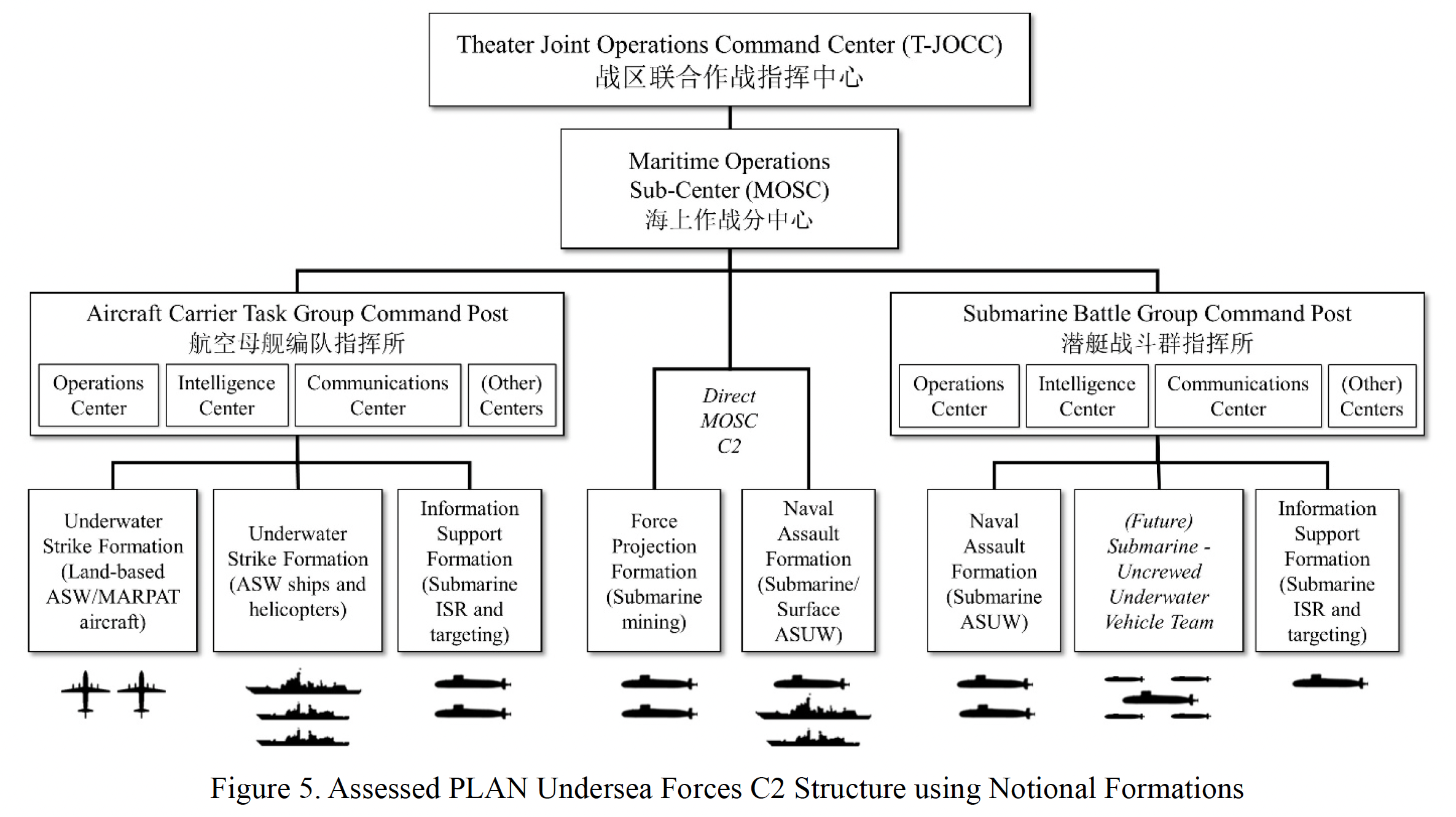

The initial phase of PLA reforms—called the “above-the-neck” reforms for its focus on changes to top-level organizations—resulted in the creation of a joint operational command system. In the new system, geographic operational theaters took over control of ships and submarines from PLAN headquarters. The introduction of new technologies in the PLAN, including longer-range reconnaissance and surveillance and longer-range conventional and strategic weapons in the submarine force, drove further changes to submarine command and control.

While the first phase of reforms focused on the “head,” the subsequent phase of “below-the-neck” reforms, which began in 2017, resulted in changes to operational units, i.e., the “body” of the PLA. The PLA Army (PLAA) and Air Force (PLAAF) experienced profound organizational change—commands were combined or eliminated, and formations were fundamentally restructured. By contrast, the PLAN saw relatively few changes to its organizational structure, remaining very similar to its pre-reform state. But even if its command relationships were not reorganized in the reforms, changes to force structure and composition had significant impacts on the PLAN submarine force.

Key findings of this report include:

- “Above-the-neck” and “below-the-neck reforms resulted in significant changes to the operational command and control of PLAN forces. Fleet organizational structure remained in place serve the PLAN’s “man, train, and equip” functions.

- The “maritime operations sub-center” (MOSC) is the newly created PLAN-run maritime component of the theater joint operations command system in each PLA operational theater command. MOSCs now exercise command and control over most PLAN submarine deployments.

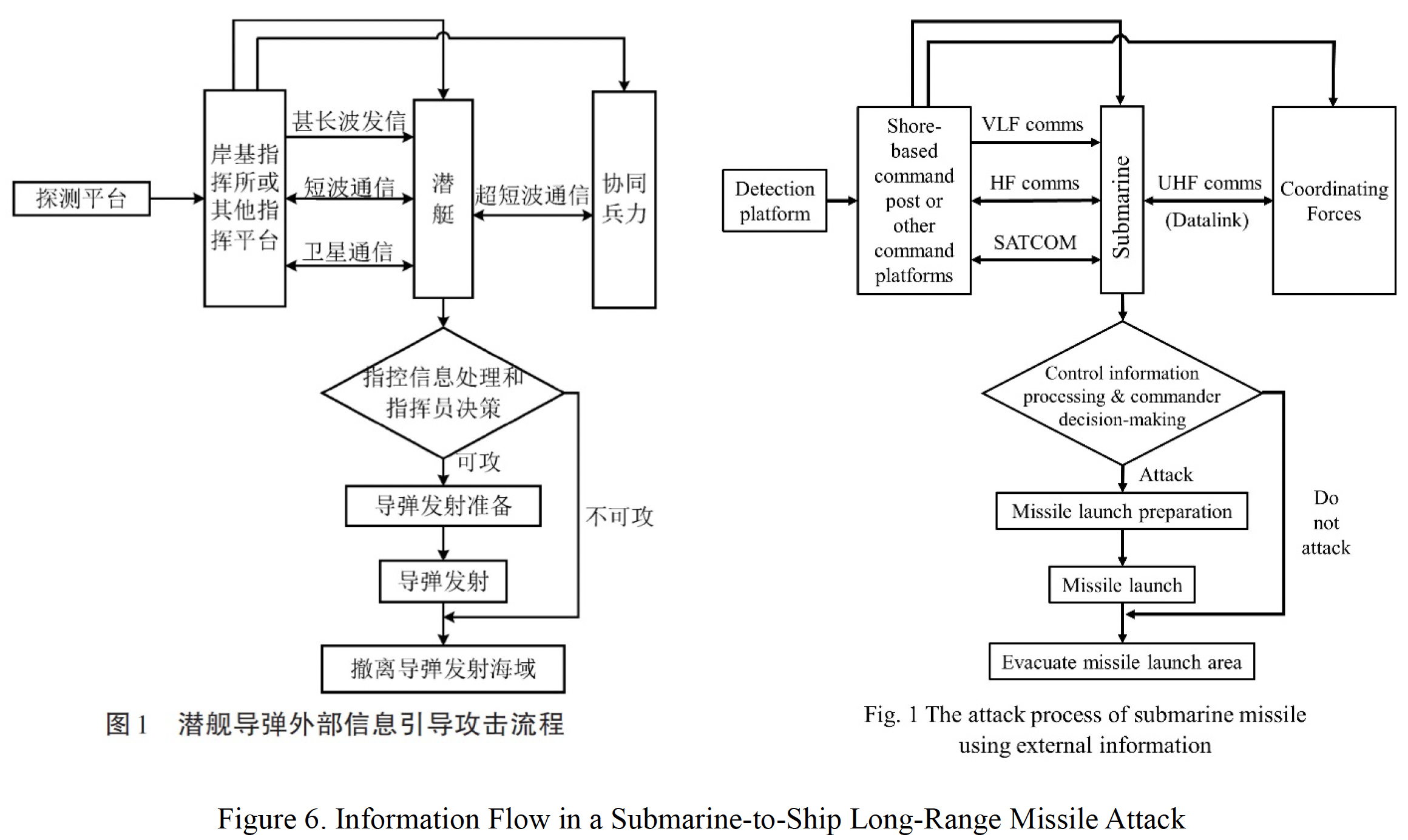

- Changes to tactical-level submarine command and control have been driven by new PLAN ships and aircraft in the fleet as well as new, longer-range weapons in the submarine force.

- The Central Military Commission’s (CMC) Joint Operations Command Center probably exercises exclusive control over ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs).

- Overseas submarine operations probably fall under the control of the CMC Joint Staff Department; however, operational theater commands have also demonstrated command and control of PLAN forces thousands of miles from China’s shores.

- “Below-the-neck” reforms in the PLAN submarine force did not result in changes to command organizational structure but did involve significant shifts in submarine fleet composition, and the attendant inter-fleet transfers of submarines and crews.

- Force structure changes were driven by the arrival of a dozen newly constructed submarines and the retirement of older nuclear and conventional submarines.

- Observed infrastructure improvements at PLAN nuclear submarine bases indicate that the PLAN will likely continue to incorporate new submarines over the next several years, probably extending the recent cycle of submarine and crew transfers.

This report comprises two sections and an appendix. Section one examines the first phase of PLA reform—the “above-the-neck” reforms—that began in 2015. This section discusses changes to joint operational command and control and its impact on PLAN submarine operations. It also goes into detail on PLAN task group organization, tactical command and control of submarines, and issues surrounding the control of strategic assets (e.g., SSBNs) and the command of foreign exercises and “far seas” operations. Section two examines the impacts of “below-the-neck” reforms and changes in submarine force structure. It also discusses the recently detected construction of submarine base infrastructure that likely portends further expansion of the PLAN submarine force. The report concludes with an appendix that offers details about PLAN submarine operational bases.

Conclusion

The PLAN submarine force has arguably undergone historical change since the 2015 “above-the-neck” reforms and 2017 “below-the-neck” reforms. Changes to command and control arrangements emphasizing joint coordination of undersea forces, the introduction of a dozen new submarines, and the retirement of even more has almost certainly resulted in impactful changes in the fleet. As the changes have settled out, they have likely resulted in an overall increase in PLAN submarine capabilities.

As outlined in this report, changes to operational command and control of undersea and other maritime forces have become clearer since the PLA’s joint operational command system was created as part of the “above-the-neck” and “below-the-neck” reforms. The theater “maritime operations subcenter,” similar to a U.S. Navy joint force maritime component commander (JFMCC) or maritime operations center (MOC) has emerged as the PLAN component under the operational theaters’ joint operations command center (T-JOCC). This command and control construct holds great promise for PLA joint operations but remains untested in a real-world contingency or conflict.

Control of PLA non-war military activities and operations abroad have apparently been consolidated under the CMC Joint Staff Department. However, the PLA’s operational theaters appear to be firmly in charge of wartime command and control and have directed operational forces thousands of miles from their respective theaters in what appears to be contingency planning exercises. How the PLA will grapple with operational control of combat forces including submarines in areas not directly related to a contingency on China’s periphery remains unclear.

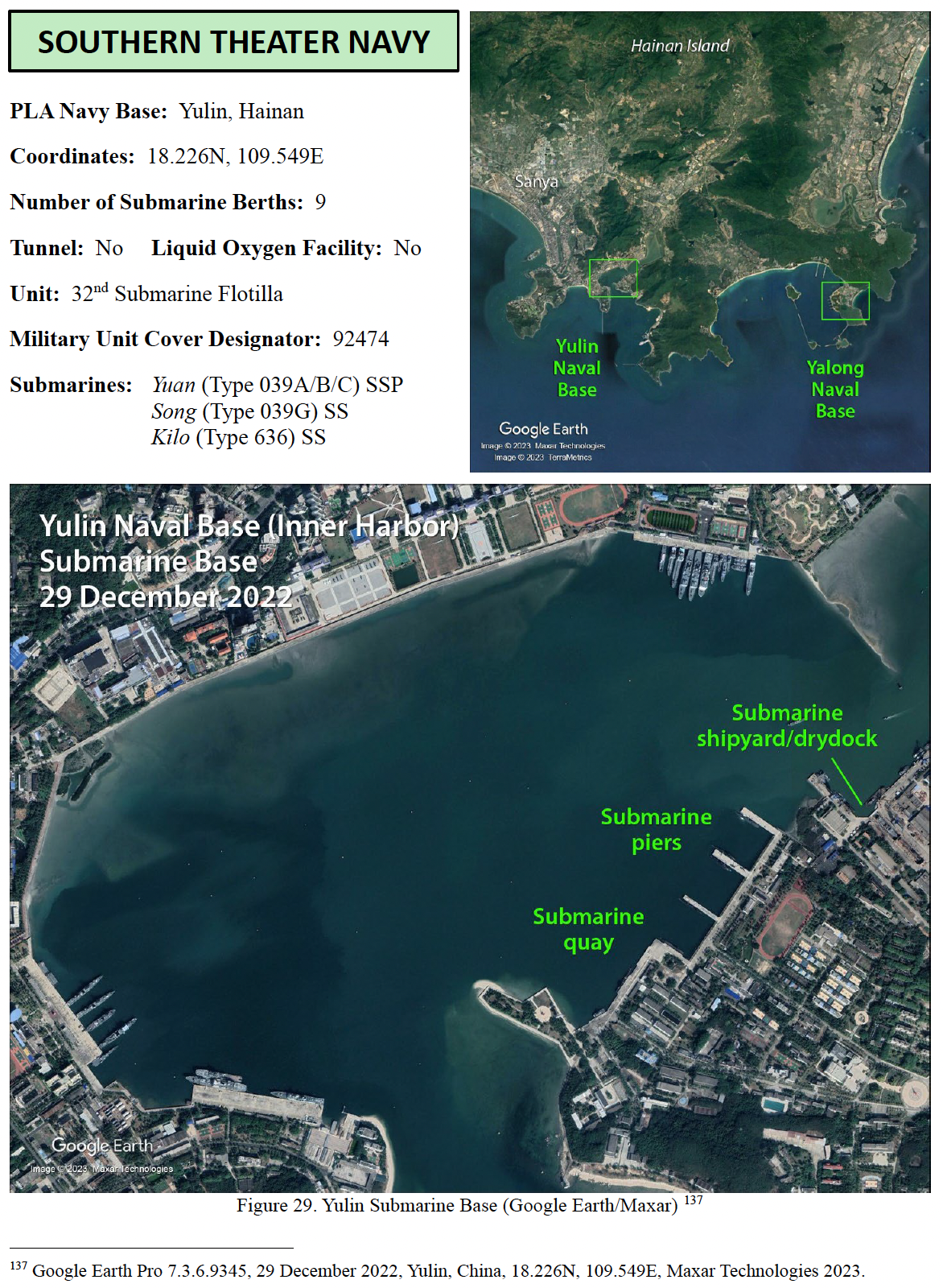

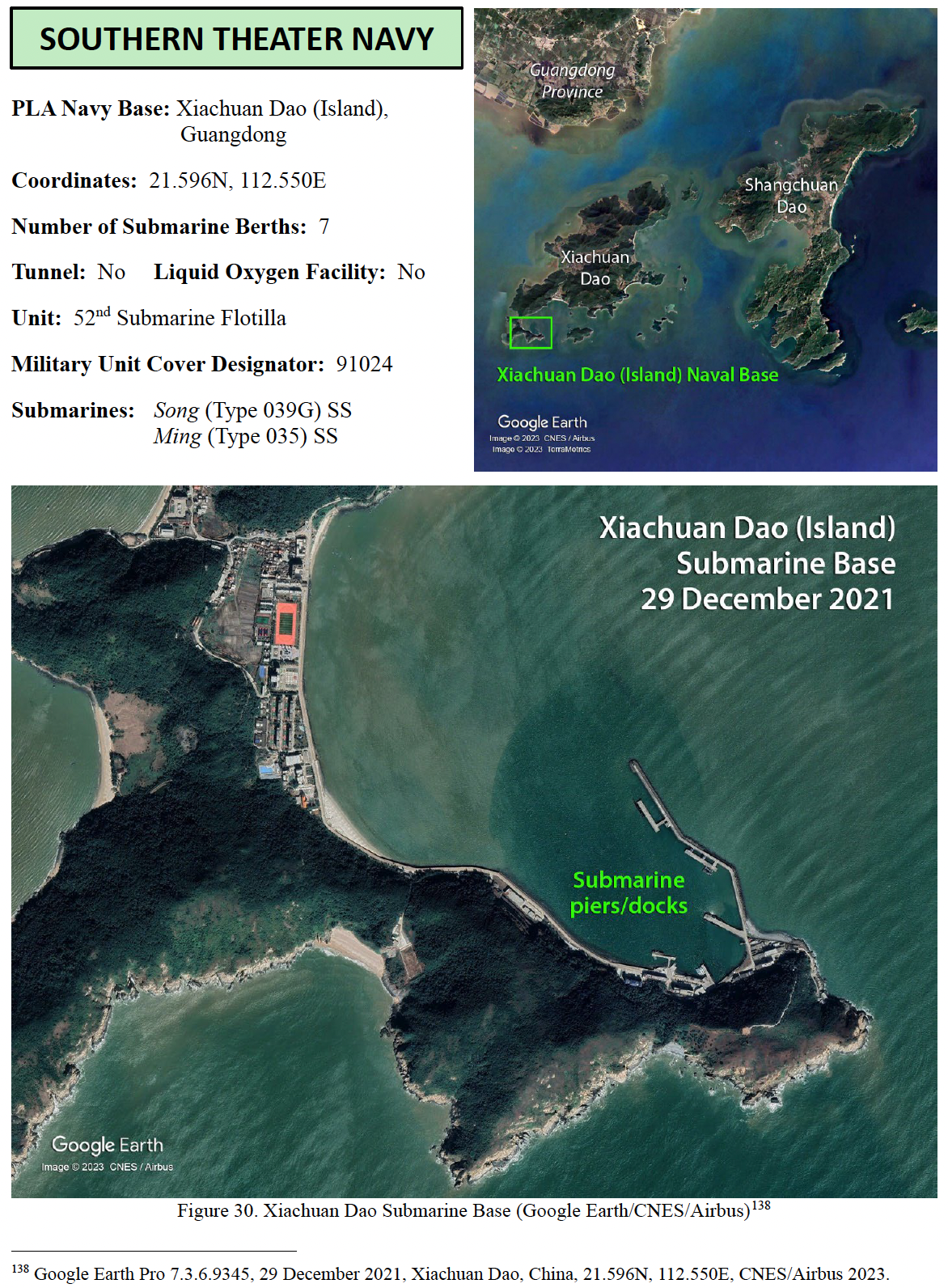

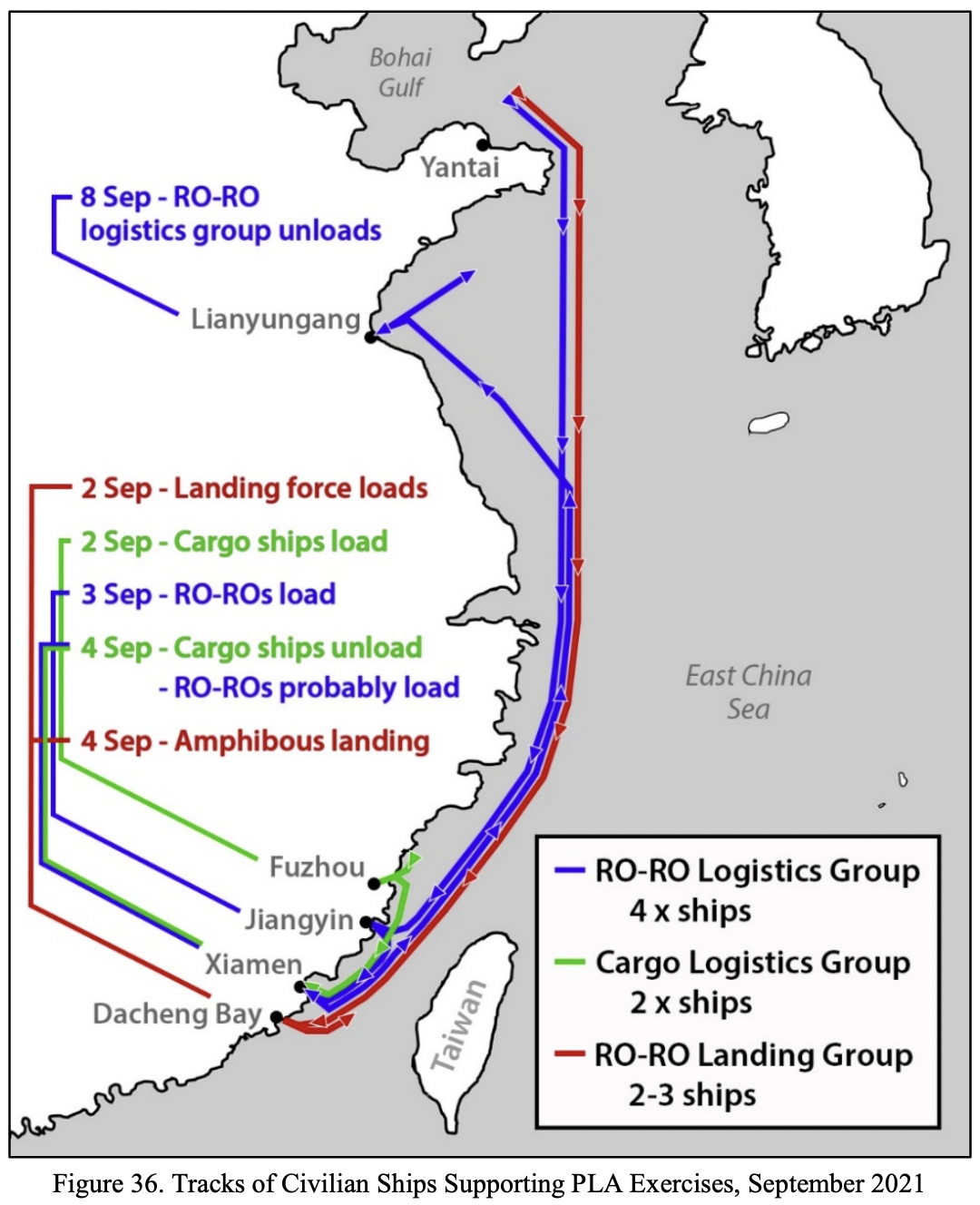

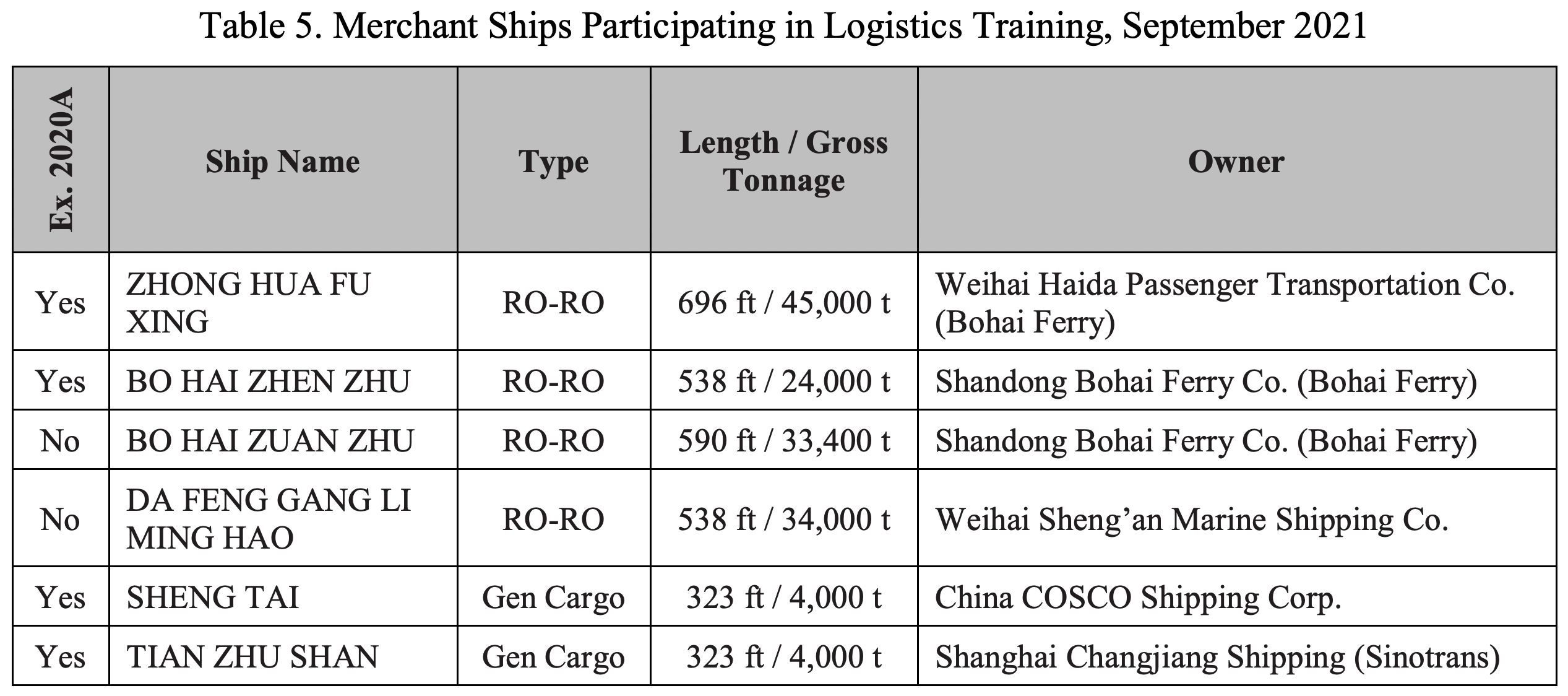

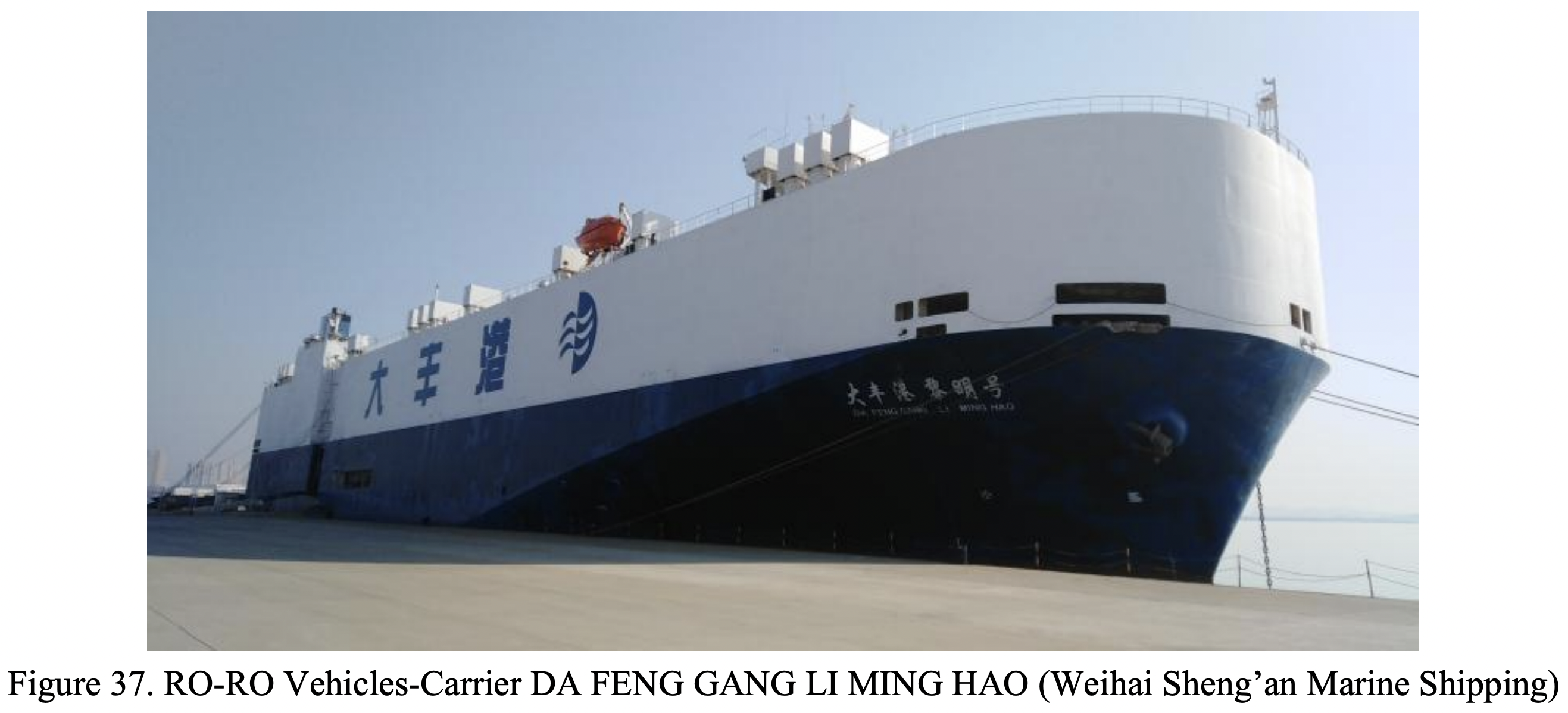

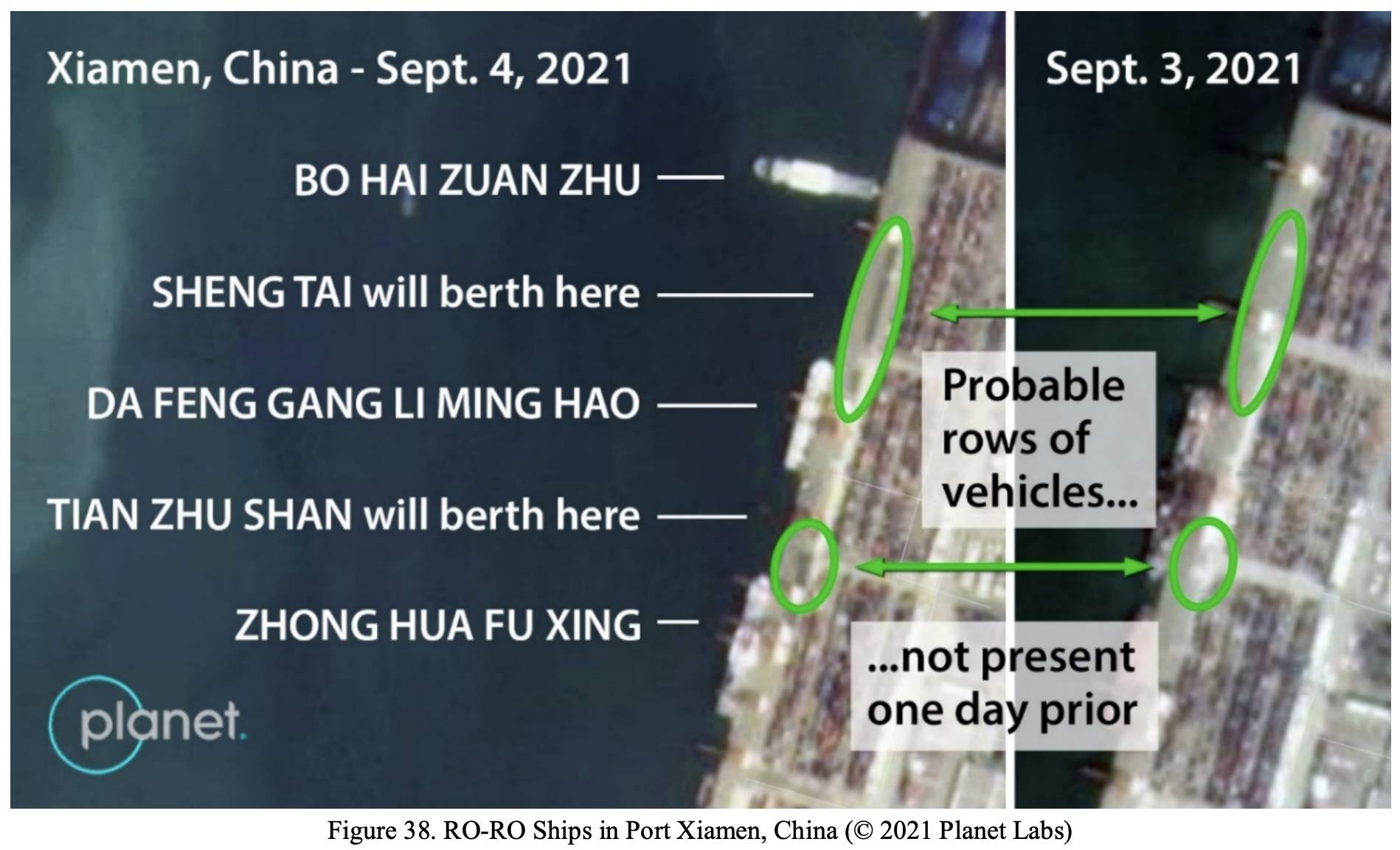

New technologies have been the principal driver of change in the PLAN submarine force over the past several years, a trend that will likely continue well into the future. Other PLA services may have reshaped their formations and command organizations to address deficiencies in how they manage operations and how they fight wars. In contrast, technology appears to drive how the PLAN submarine force fights, which then necessitates commensurate changes in command and control.